AI chat bots skim the web for information on all sorts of subjects, so in a way they allow us to take the pulse of public perception on various issues and topics. Many people have “interviewed” chat bots about current events, creative ideas and, of course, asked questions related to their employment (we all want some peace of mind that AI isn’t taking our jobs…yet). So, here at PMA I (Skyla) decided to “talk” with an AI chat bot on some general, specific, and local topics related to the fields of architecture and historic preservation. Below are the highlights, but first, a bit on how I chose which bot to interview.

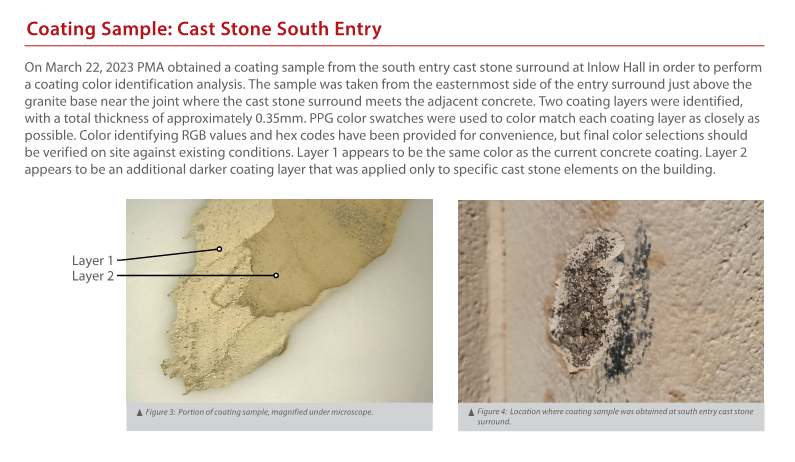

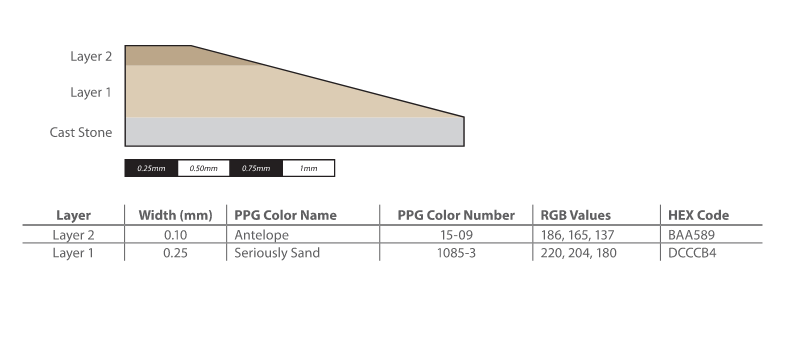

The Chat Bot:

Ever since Chat GPT took the spotlight there have been many AI chat bots developed, some with very specific purposes and pricing attached. However, I decided to interview the most well-known free chat bot: Chat GPT, which is owned and developed by OpenAI. Given it is very accessible to the public, the evolution and continued learning of this bot is being advanced by a diverse user pool with a wide range of interests. However, it’s worth noting that it is difficult to tell how much a chat bot knows about its individual users, and how much that creates bias in the conversation. It’s also important to remember that most of these bots have limited knowledge of events after 2021, and are apt to make mistakes or give inaccurate information now and then. Most AI chat bots included disclaimers warning that they should not be used for advisory purposes. Runner-ups to Chat GPT include Google Bard, which is owned by Google and developed by Google AI, and Bing Chat, which is owned by Microsoft and based on OpenAI’s GPT-4.

The Interview:

I was genuinely interested in Chat GPT’s responses to a range of both serious and silly questions. On Friday May 5, 2023 I sat down to conduct my chat bot interview. This is how it went.

*Note: I did have to edit down certain answers for length and redundancy since this chat bot really likes to write five-paragraph essays in response to every question! All italicized text in the following section are Chat GPT’s responses.

First, I wanted to gauge Chat GPT’s “understanding” of historic preservation and its relationship with architecture.

• What is architectural historic preservation?

“Architectural historic preservation refers to the practice of identifying, protecting, and maintaining historic buildings, structures, and other built environments that are considered to be culturally or historically significant. The goal of architectural historic preservation is to ensure that these structures are preserved for future generations to enjoy and appreciate.

The process of architectural historic preservation typically involves researching and documenting the history and significance of a structure, assessing its condition, and developing a plan for its restoration and maintenance. This can involve a range of activities, from basic maintenance and repair to more complex renovation and restoration projects that seek to maintain the integrity of the original design and construction.

Architectural historic preservation is an interdisciplinary field that draws on a range of disciplines, including architecture, engineering, history, archaeology, and cultural anthropology. It is guided by principles of cultural heritage conservation and seeks to balance the preservation of historic structures with the practical needs of modern society.”

• Why should we preserve historic buildings?

“1. Cultural heritage: Historic buildings often serve as tangible reminders of our shared cultural heritage, representing important moments in history and cultural achievements of past generations. By preserving historic buildings, we can better understand and appreciate our shared cultural heritage.

2. Educational opportunities: Historic buildings can provide important educational opportunities, offering insights into the history of architecture, engineering, and construction techniques, as well as the social and cultural contexts in which these buildings were constructed.

3. Economic benefits: Historic buildings can serve as important tourist attractions, generating revenue and supporting local economies. They can also contribute to the unique character and charm of a city or town, attracting businesses, residents, and visitors.

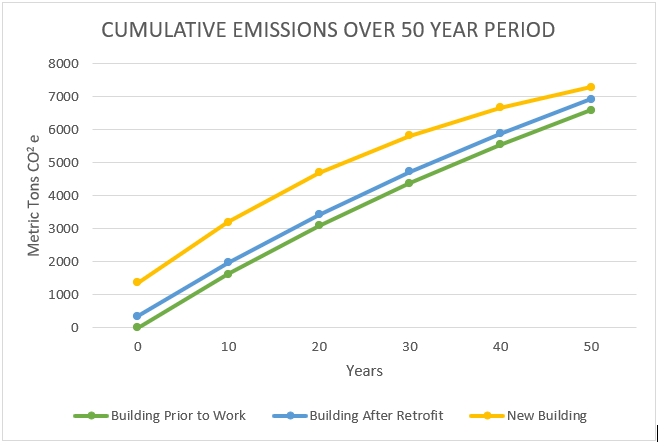

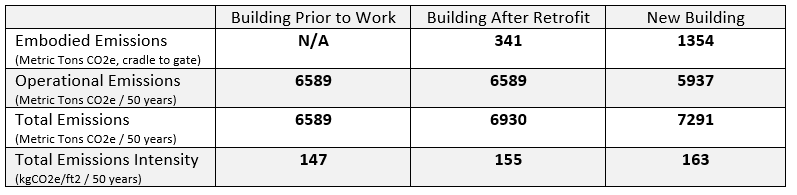

4. Sustainability: The preservation of historic buildings can contribute to sustainability by promoting the reuse of existing structures, reducing the need for new construction, and preserving the embodied energy and materials in historic buildings.

5. Sense of place: Historic buildings can contribute to a sense of place and community identity, providing a connection to the past and a sense of continuity with previous generations.”

• Are historic buildings important?

For this response, the chat bot summarized its previous answer from a list into a paragraph. However, just a few questions into our conversation I was already impressed—Chat GPT gave me a well-rounded birds-eye view of the major goals and benefits of architectural historic preservation, a useful introduction for the uninitiated. Personally, I found the mention of historic preservation as an interdisciplinary field to be obvious but uncanny, considering I wrote my whole terminal project for my HP masters on this topic, but I’m sure I’m just reading into it…

• Is historic preservation sustainable?

“Yes, historic preservation can be a sustainable approach to building and development. By preserving existing buildings and structures, we can reduce the need for new construction and conserve resources. In addition, many historic buildings were built with durable materials and construction techniques that have proven to be long-lasting, making them inherently sustainable.

Furthermore, the restoration and rehabilitation of historic buildings can often include sustainable design and construction practices, such as the incorporation of energy-efficient technologies, the use of renewable materials, and the implementation of green infrastructure. These practices can help to reduce the environmental impact of historic buildings while preserving their cultural and historic significance.

Additionally, the preservation of historic buildings can promote sustainable economic development by supporting local businesses and providing jobs in skilled trades and construction. By preserving the character and identity of a place, historic preservation can also contribute to the social and cultural sustainability of a community.

Overall, historic preservation can be a sustainable approach to building and development, promoting the conservation of resources, the use of durable materials and construction techniques, and the incorporation of sustainable design and construction practices.”

This response was not as well rounded or as thorough as I would have hoped based on the bots previous responses summarizing preservation and its importance. I expected some discussion of embodied carbon, or how buildings consume more energy than transportation or industry respectively, and how reusing and improving our existing building stock is more sustainable than producing new “green” buildings. The AI also appears to default to the assumption that all historic buildings are of “durable” materials and construction. Despite my effort to phrase my questions in a simple manner and without bias, the bot does not seem interested in discussing the challenges or cons related to the sustainability of historic buildings, and instead only focuses on the positives. My observation at this point is less about the content of the response and more a criticism of AI chat bots, and how we should remain critical of the way they present information to us. How useful is this kind of non-holistic response in practice or the dissemination of information?

Next, I wanted to gauge general perceptions around social issues and impacts attached to historic preservation. (Yes, some of these questions are worded in a very elementary way, but I was curious how the bot would respond!)

• Is architectural historic preservation good or bad?

“There is no simple answer to whether architectural historic preservation is good or bad, as it depends on various factors and perspectives.

From a cultural heritage perspective, architectural historic preservation is generally regarded as a positive practice, as it helps to preserve and celebrate the built environment of past generations. Historic buildings can provide important educational and cultural resources, contributing to the sense of place and community identity.

From an environmental perspective, architectural historic preservation can also be a positive practice, as it promotes the reuse of existing structures and reduces the need for new construction, which can be resource-intensive and have negative impacts on the environment.

However, from an economic perspective, some argue that architectural historic preservation can be costly and may limit development opportunities. Additionally, there may be challenges associated with balancing the need for preservation with the practical considerations of modern use and occupancy.

Overall, the benefits and drawbacks of architectural historic preservation are context-specific and depend on a range of factors, including the cultural and historic significance of the building, the resources available for preservation and maintenance, and the needs and priorities of the community.”

While this very high-level answer does touch on a few ‘good’ and ‘bad’ notes, I was hoping to force the chat bot into mentioning some of the more nuanced issues within preservation such as accessibility, how it has led to the gentrification of neighborhoods, or how our preservation tools and processes in the United States are often discriminatory towards minority groups and people of color. With my next, more direct, question I was able to eek out a brief mention of these issues, but again, herein lies an issue with AI bots—they may be able to help us learn about new subjects, but unless we ask the right (hard) questions, we may not get the full picture.

The following response is paraphrased as many of the talking points established by the bot were becoming redundant.

• Does historic preservation hurt or help people?

“…historic preservation can also hurt people if it limits development opportunities or creates financial burdens for property owners. In some cases, preservation efforts may also perpetuate problematic aspects of the past, such as historic patterns of inequality or discrimination.

Moreover, the preservation of historic buildings may also have broader social and economic impacts, such as contributing to gentrification or displacement of residents, which can have negative consequences for low-income and marginalized communities.”

• Is it okay to demolish a historic building?

“Whether it is okay to demolish a historic building depends on a range of factors, including the cultural and historic significance of the building, the condition of the structure, and the needs and priorities of the community.

In some cases, it may be necessary to demolish a historic building due to safety concerns, such as when the building is structurally unsound and poses a risk to public health and safety. However, in many cases, the demolition of historic buildings is a controversial issue, as it can result in the loss of important cultural and historic resources and erode the character and identity of a place.

Before deciding to demolish a historic building, it is important to consider alternatives, such as rehabilitation or adaptive reuse. Rehabilitation involves repairing and restoring a building to its original condition, while adaptive reuse involves converting a historic building to a new use while preserving its historic features and character.

Moreover, it is important to engage in a community-wide conversation about the preservation of historic buildings, as the decision to demolish a historic building can have significant cultural, economic, and environmental impacts on the community. Community input can help to ensure that the needs and priorities of all stakeholders are taken into account and that the decision reflects the values and aspirations of the community.”

Having finally forced the chat bot to mention some tougher issues, I was hoping to see those topics resurface with more depth in the response to this question, but to no avail. Don’t even get me started on the semantics of rehabilitation, preservation, adaptive reuse, and all the other terminology that gets tossed around and confused—you can check out our “Practical Guide to Preservation Terminology ” blog for a deep dive on that discussion!

Having tackled some tough high-level questions, I was interested in getting a more local perspective, so I wanted to ask a few Portland-specific questions. However, that proved to be difficult, and Chat GPT’s responses were a mixture of accurate national history that happens to be locally applicable, and downright wrong information pertaining to PDX.

For instance, when asked how historic preservation has shaped the City of Portland, Oregon, the bot first mentioned that “Portland has a rich architectural history, with a diverse array of architectural styles and building types that reflect the city’s growth and development over time. In the 1960s and 1970s, many historic buildings in Portland were threatened with demolition due to urban renewal and highway construction projects.” This response is vague, and not technically incorrect, albeit not very informative either. However, Chat GPT then went on to boldly claim that Pioneer Courthouse Square and the Pearl District are historic districts, which is obviously untrue, although someone unfamiliar with Portland’s preservation landscape probably wouldn’t know that. After I corrected the bot, it conceded that these are not designated districts, but that they still have historic significance. Those of us in preservation know that distinction is critical and has real-world implications, but the AI has not yet gleaned this type of insight.

Selfishly, I also wanted to know whether Chat GPT would name PMA as a leader in historic preservation in Portland. Despite several attempts, the bot would only give me a smattering of seemingly random architecture firms, most of them national or international that happen to have a PNW office, but not necessarily preservation services. Of course this was disappointing considering PMA has been around for 20 years this year (woohoo!), but I wasn’t surprised given the previous inaccuracies and lack of specific information provided by the AI. I even asked about PMA directly, and the bot fabricated multiple timelines, projects, and awards for our firm, none of which was remotely correct but mildly entertaining (I wish I actually did get to work on some of the buildings it claimed we did!)

Before wrapping up, I wanted to do a quick lightning round of questions to see if AI is coming for my job (or yours) anytime soon (it doesn’t know where I work, so I think I’m safe for now!) I’ll just leave these here for those interested in skimming Chat GPT’s stab at being a preservationist.

• How do I know if a building is historic?

“Determining whether a building is historic typically involves considering a number of different factors, such as its age, architectural style, significance to local history or culture, and whether it is listed on a historic register or has been designated as a historic landmark.

Here are some general guidelines that can help you determine if a building is historic:

1. Age: Historic buildings are typically older than 50 years, although this can vary depending on the context and location.

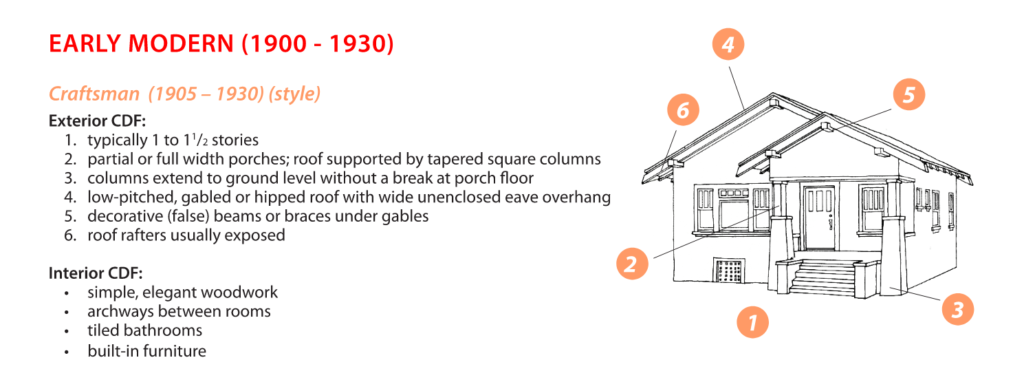

2. Architectural Style: Historic buildings often reflect a particular architectural style that was popular during a specific period. For example, Victorian, Art Deco, and Mid-Century Modern are all styles that are commonly associated with historic architecture.

3. Significance: Historic buildings may have played a significant role in the history or culture of the local community, or have been associated with important individuals or events.

4. Historic Register: Historic buildings may be listed on a national, state, or local historic register, which recognizes their cultural, architectural, or historical significance.

If you are unsure whether a building is historic, you can check with your local historical society, preservation organization, or government agency that oversees historic preservation. They may be able to provide more information on the building’s history and significance, and whether it is considered to be historic.”

• How can I preserve a historic building?

“Preserving a historic building requires a combination of maintenance, repair, and restoration work to ensure that the building’s historic fabric and character are maintained. Here are some general steps to follow when preserving a historic building:

1. Conduct a historic assessment: Before beginning any preservation work, it is important to conduct a thorough assessment of the building’s historic fabric, including its architectural features, building materials, and any existing damage or deterioration.

2. Develop a preservation plan: Based on the results of the historic assessment, develop a comprehensive preservation plan that outlines the scope of work, timeline, and budget for the project.

3. Conduct regular maintenance: Regular maintenance is essential to prevent deterioration and damage to historic buildings. This may include tasks such as cleaning gutters, repairing leaks, and sealing cracks.

4. Repair damage: When damage occurs to historic fabric, it is important to repair it using materials and techniques that are compatible with the original construction. This may include repairing masonry, replacing damaged woodwork, or patching plaster.

5. Restore missing or deteriorated elements: In some cases, historic elements may be missing or deteriorated beyond repair. In these cases, it may be necessary to restore the element using new materials that are compatible with the original construction.

6. Use appropriate materials: When working on historic buildings, it is important to use materials that are appropriate for the building’s age and style. This may include using traditional building materials such as lime mortar or wooden shingles.

7. Work with preservation professionals: It is important to work with professionals who are experienced in historic preservation, including architects, engineers, and contractors. They can provide guidance and expertise to ensure that preservation work is done appropriately and effectively.

Preserving a historic building requires ongoing effort and attention, but the rewards are great in terms of preserving the character and history of the built environment.”

• Who can help me preserve a historic building?

“There are several professionals who can assist with the preservation of a historic building:

1. Historic preservation architects: These professionals specialize in the preservation and restoration of historic buildings. They can assist with a wide range of services, including historic assessments, preservation planning, and construction management.

2. Structural engineers: Structural engineers can provide guidance on preserving the structural integrity of historic buildings, as well as ensuring that any restoration work is done safely and effectively.

3. General contractors: Contractors who specialize in historic preservation can provide a range of services, from general maintenance and repair to full-scale restoration work.

4. Historic preservation organizations: Local and national historic preservation organizations can provide guidance and resources for preserving historic buildings, as well as funding opportunities for preservation projects.

5. Government agencies: State and local government agencies may have programs in place to support historic preservation, including grants, tax incentives, and regulatory guidance.

When seeking assistance with the preservation of a historic building, it is important to work with professionals who have experience and expertise in historic preservation. They can help ensure that preservation work is done appropriately and effectively, while preserving the character and history of the building.”

• How can I safely clean historic masonry?

“Cleaning historic masonry requires special care and attention to ensure that the materials and surfaces are not damaged in the process. Here are some general steps to follow when cleaning historic masonry:

1. Determine the type of masonry: Different types of masonry, such as brick, stone, or stucco, may require different cleaning methods and products.

2. Test a small area: Before cleaning the entire surface, test a small area to ensure that the cleaning method and product will not damage the masonry.

3. Use gentle cleaning methods: Avoid using abrasive or harsh cleaning methods that can damage the masonry. Instead, use gentle methods such as water, low-pressure washing, or a soft-bristled brush.

4. Use appropriate cleaning products: Choose cleaning products that are specifically designed for historic masonry and that will not damage the surface. Avoid using bleach, acids, or other harsh chemicals.

5. Protect surrounding areas: When cleaning masonry, be sure to protect surrounding areas, such as landscaping or other surfaces, from the cleaning products and runoff.

6. Work from the bottom up: When cleaning vertical surfaces, work from the bottom up to prevent streaking and ensure that the cleaning solution is evenly distributed.

7. Rinse thoroughly: After cleaning, rinse the surface thoroughly with water to remove any remaining cleaning solution.

It is also recommended to consult with a professional historic preservationist or masonry restoration expert before attempting to clean historic masonry, as they can provide specific guidance and recommendations based on the unique characteristics of the building and its materials.”

• Should I paint historic brick?

“Whether or not to paint historic brick is a contentious issue within the preservation community. In general, it is recommended to avoid painting historic brick whenever possible, as painting can obscure the brick’s texture and historic character, and may even damage the brick over time.

However, there are some circumstances where painting historic brick may be necessary or desirable. For example, if the brick is severely damaged or discolored and cannot be restored through other means, painting may be a viable option. Additionally, in some cases, painting may be used to match the appearance of surrounding buildings or to unify a façade that has been altered over time.

Before deciding to paint historic brick, it is important to consult with a professional historic preservationist or architectural conservator. They can provide guidance on the appropriateness of painting in a specific context, and recommend appropriate paint types and application methods to ensure that the historic fabric of the building is preserved.”

• What should everybody know about architecture and historic preservation?

“Here are a few things that everybody should know about architecture and historic preservation:

1. Historic preservation is not just about saving old buildings; it is also about preserving our cultural heritage and the stories of the people who lived and worked in those buildings.

2. Architecture and historic preservation are not just for the wealthy; they are important for communities of all income levels and backgrounds.

3. The principles of historic preservation can be applied to modern architecture and design, helping to create buildings and spaces that are both functional and aesthetically pleasing.

4. Preservation is not just about keeping buildings in their original state; it can also involve adapting and reusing them to meet the needs of modern society.

5. Preserving historic buildings and neighborhoods can have economic benefits, including increased property values and tourism revenue.

6. Architects and designers play a critical role in historic preservation, using their knowledge and skills to help communities preserve and adapt their built heritage for future generations.

7. Preservation is a collaborative effort that involves many different stakeholders, including property owners, government agencies, community organizations, and preservation professionals.

Historic preservation is a dynamic field that is constantly evolving, with new technologies, materials, and approaches emerging all the time.”

• How can AI be used in historic preservation?

“Artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to be used in several ways for historic preservation. Here are some examples:

1. Digital documentation: AI can be used to create digital 3D models of historic buildings, which can be used for documentation, analysis, and visualization purposes. These models can be used to detect changes in the building over time and to help with restoration efforts.

2. Building monitoring: AI can be used to monitor the condition of historic buildings in real-time. Sensors and cameras can be installed to capture data on the building’s structural integrity, temperature, humidity, and other factors. This data can then be analyzed to detect potential issues before they become major problems.

3. Historical research: AI can be used to analyze historical documents and data to uncover new insights about historic buildings and their significance. For example, AI can be used to analyze newspaper articles, photographs, and other historical records to gain a deeper understanding of the building’s history.

4. Conservation and restoration: AI can be used to assist with the conservation and restoration of historic buildings. For example, AI can be used to analyze paint samples to determine the original colors of a building, or to analyze photographs to identify changes to the building over time.

Overall, AI has the potential to be a powerful tool in historic preservation. By using AI to analyze data and monitor historic buildings, preservationists can gain a deeper understanding of the building’s history and make informed decisions about how to preserve it for future generations.”

• How can AI be used in architecture?

“Artificial intelligence (AI) can be used in architecture in several ways. Here are a few examples:

1. Design optimization: AI can be used to optimize the design of buildings by analyzing data on factors such as energy efficiency, structural integrity, and aesthetics. This can lead to more efficient and sustainable building designs.

2. Energy modeling: AI can be used to create energy models of buildings, which can be used to predict energy usage and identify opportunities for energy savings. This can help architects design buildings that are more energy-efficient and reduce their environmental impact.

3. Generative design: AI can be used to generate new design ideas and solutions. By inputting certain parameters, such as the site conditions and client requirements, AI algorithms can generate multiple design options that meet those criteria. This can help architects explore a wider range of design possibilities and find innovative solutions.

4. Construction management: AI can be used to monitor construction sites and manage the construction process. For example, AI can be used to track progress, monitor safety, and identify potential issues before they become major problems.

5. Facility management: AI can be used to manage buildings after they are constructed. For example, AI can be used to monitor building systems such as heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) and lighting to optimize energy usage and reduce maintenance costs.

Overall, AI has the potential to revolutionize the field of architecture by enabling architects to design more efficient, sustainable, and innovative buildings.”

The answers compiled by the bot about how to tell if a building is historic, who to consult, and the general preservation process are generally correct. Of course, the recommendation to chat with a professional before doing any work is always good advice (and we’re here if you have questions!) I am a little skeptical as to AI’s current ability to perform some of the tasks it outlined in making a case for its usefulness within the architecture and historic preservation industries, but that may be because we have yet to see all these possibilities tested in wide scale practice. Luckily, human intervention will always be a requirement in preservation, as robots (currently) lack an appreciation for culture or capacity for sentimentalism, nostalgia, or intangible value.

If you have made it this far, congratulations! This blog is a long one, and it’s been an interesting ride. Since you’ve made it this far, I’ll let you in on a little secret: That social media post that sent you here was written by Chat GPT too!

In Conclusion

I wasn’t quite sure how this conversation would go, and since this wasn’t a particularly scientific experiment, I was prepared to go off script. I’ll also admit some of my questions were a bit cheeky! However, in general I was impressed with Chat GPT’s responses and the AI’s ability to summarize a wide range of issues, albeit the answers were sometimes vague or redundant. My general impression is that a read-through of these questions and answers would give the average person a pretty good idea of the major focal points and issues surrounding architectural historic preservation. But the greater takeaway, in my opinion, is to continue to be critical of this powerful technology, especially when you are asking questions about topics you do not have enough knowledge of to discern fact from AI fiction.

Blog post written by Skyla Leavitt, PMA Associate.

Photo of Monmouth Evangelical Church, Monmouth Oregon.

Photo of Monmouth Evangelical Church, Monmouth Oregon. Current lower level space

Current lower level space Rendering of possible use of lower level space

Rendering of possible use of lower level space