Schools come in all shapes and sizes. They are one-story and two-story. Schools serve young children, teenagers, and adults alike, and they are designed in all manner of style. In most instances, schools appear to be historic because of these architectural features. However, there is another yard stick with which to measure school building’s role in architectural history. As with all things, time changes our understanding and perspective, and educational theory is no different. Each school building reflects modern thought and beliefs of the era.

When imagining a school that is two-stories, designed in a classical, Spanish, or other revival style with a central corridor flanked by classrooms, it is likely to be a school from the Progressive era of education. The Progressive Era spans from the end of the nineteenth century to World War II. During this period, there was a shift from informal education to an organized system structed by putting age groups into grade levels and creating a curriculum based on intellectual rigor and mental discipline.

EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY SCHOOL DESIGN

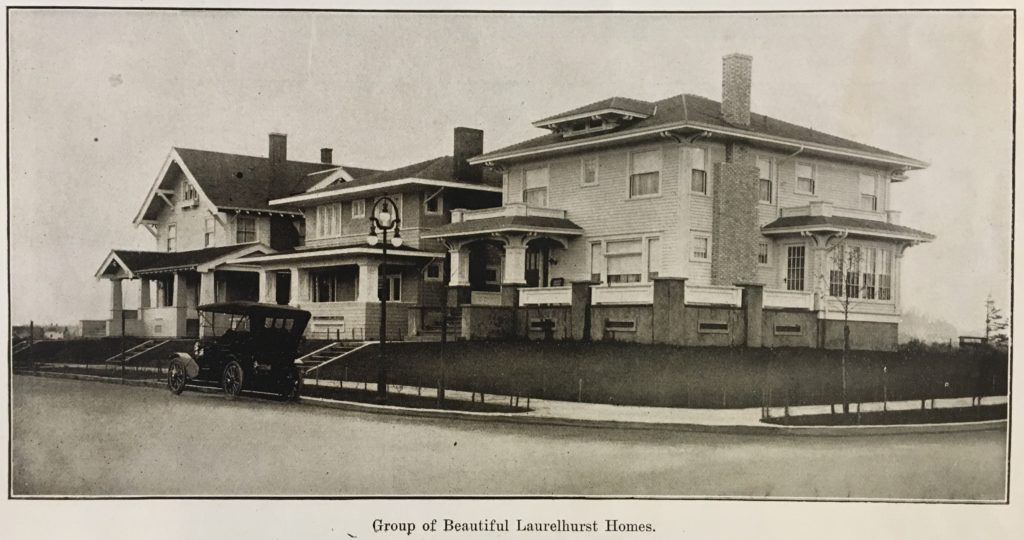

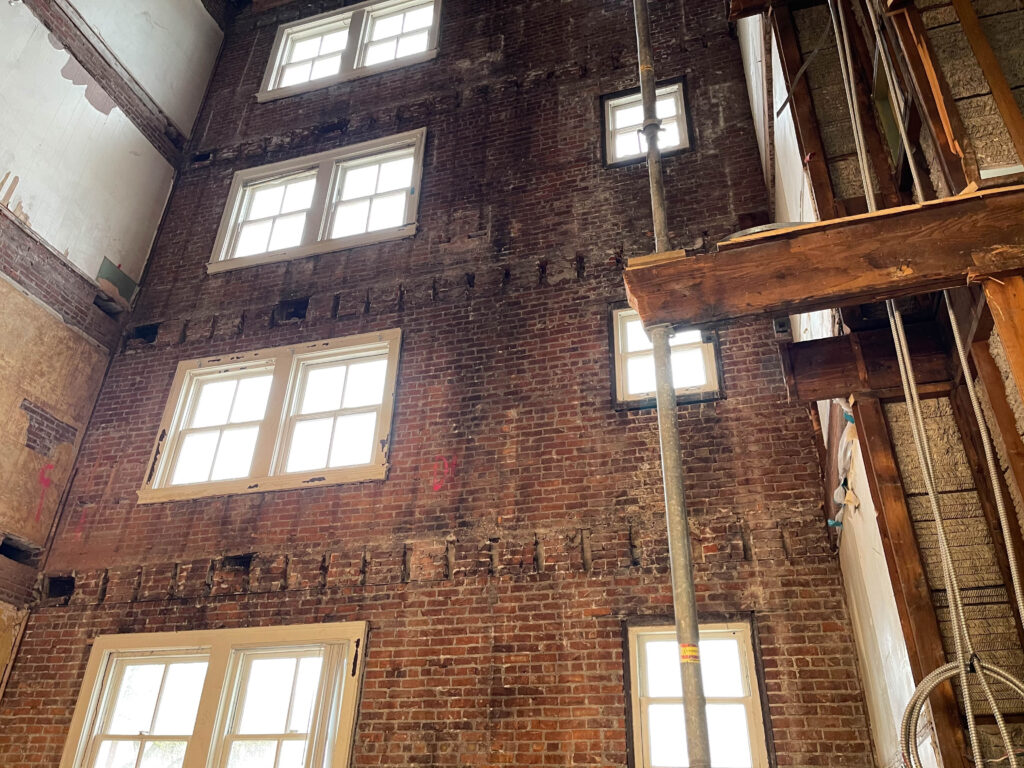

By the early twentieth century, school buildings were becoming more specialized and standardized as educators pushed for more control of school design. Plan books and design guides for educational buildings were introduced. There was a movement to make schools a healthier environment, improving ventilation and illumination. H-plan schools were introduced to bring more light and air into classrooms. Early twentieth-century school buildings typically featured traditional architectural styles, monumental designs, symmetrical facades, oversized entrances, and rectangular plans. Designed as civic monuments, the architectural focus was on building a school that would be a source of community pride. [1]

However, despite various applied stylistic details on the exteriors, the interiors were generally the same. The classroom was the basic building block for the school building, stacked vertically and horizontally to form a school. Classrooms were identical and all featured fixed desks facing the teacher at the front of the room with windows along one wall providing a single-direction light source. The emphasis was on order and authority. [2]

In 1918, the federal Office of Education published Cardinal Principles of Secondary Education. It established a list of seven key elements that education should encompass: command of basic skills, health, family values, vocation, civic education, worthy use of leisure time, and ethical character. Clearly influenced by Progressive ideals, the publication emphasized personal development rather than academic criteria. [3] It developed seven tenets of Progressive education: freedom to develop naturally; interest in the motive of all work; the teacher as a guide, rather than task-master; scientific study of pupil development; greater attention to conditions that affect a child’s physical development; co-operation between school and home to meet the needs of child-life; and the Progressive as a leader in educational movements. Progressive educational ideals were being widely implemented in schools by the 1930s. [4]

There was a considerable lack of new schools constructed between 1930 and 1945, due to a lack of funding during the Great Depression and lack of available building materials during World War II. Educators at the 1947 National Conference for the Improvement of Teaching recommended a ten-billion-dollar building program over the next decade to meet the classroom demand, estimating that “between 50 and 75 percent of all school buildings were obsolete and should be replaced immediately.” [5] At the time, general consensus among educators was that the lifespan of a school was 25 to 50 years after which new teaching methods and technology made it obsolete. Moreover, the population of the United States was increasing at a faster rate than schools could keep up with and soon overcrowded schools became commonplace. New schools were desperately needed, and like the previous Progressive era schools reflected education theory of the day, so too did mid-century schools.

MID-CENTURY SCHOOL DESIGN AND PLANNING

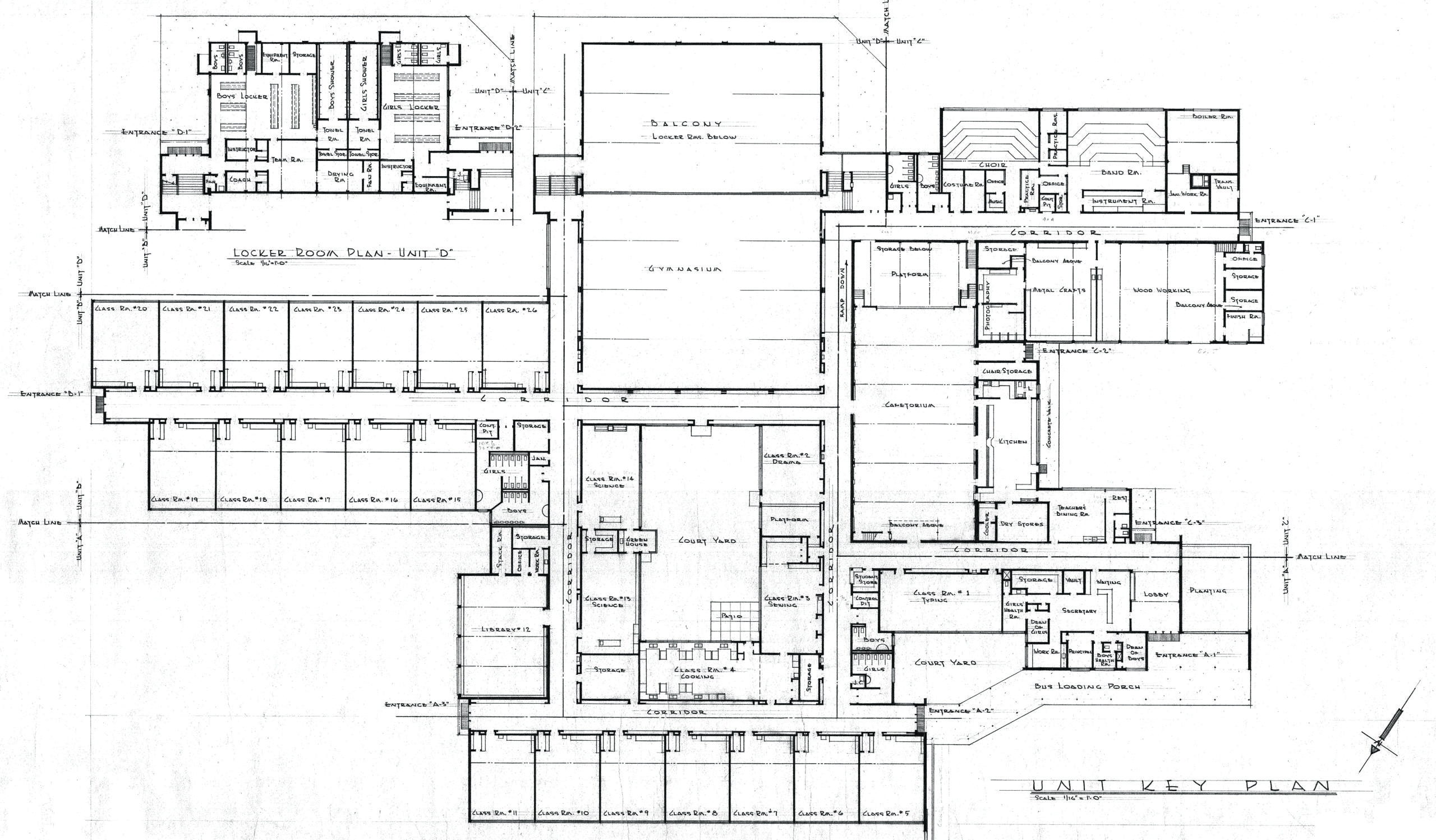

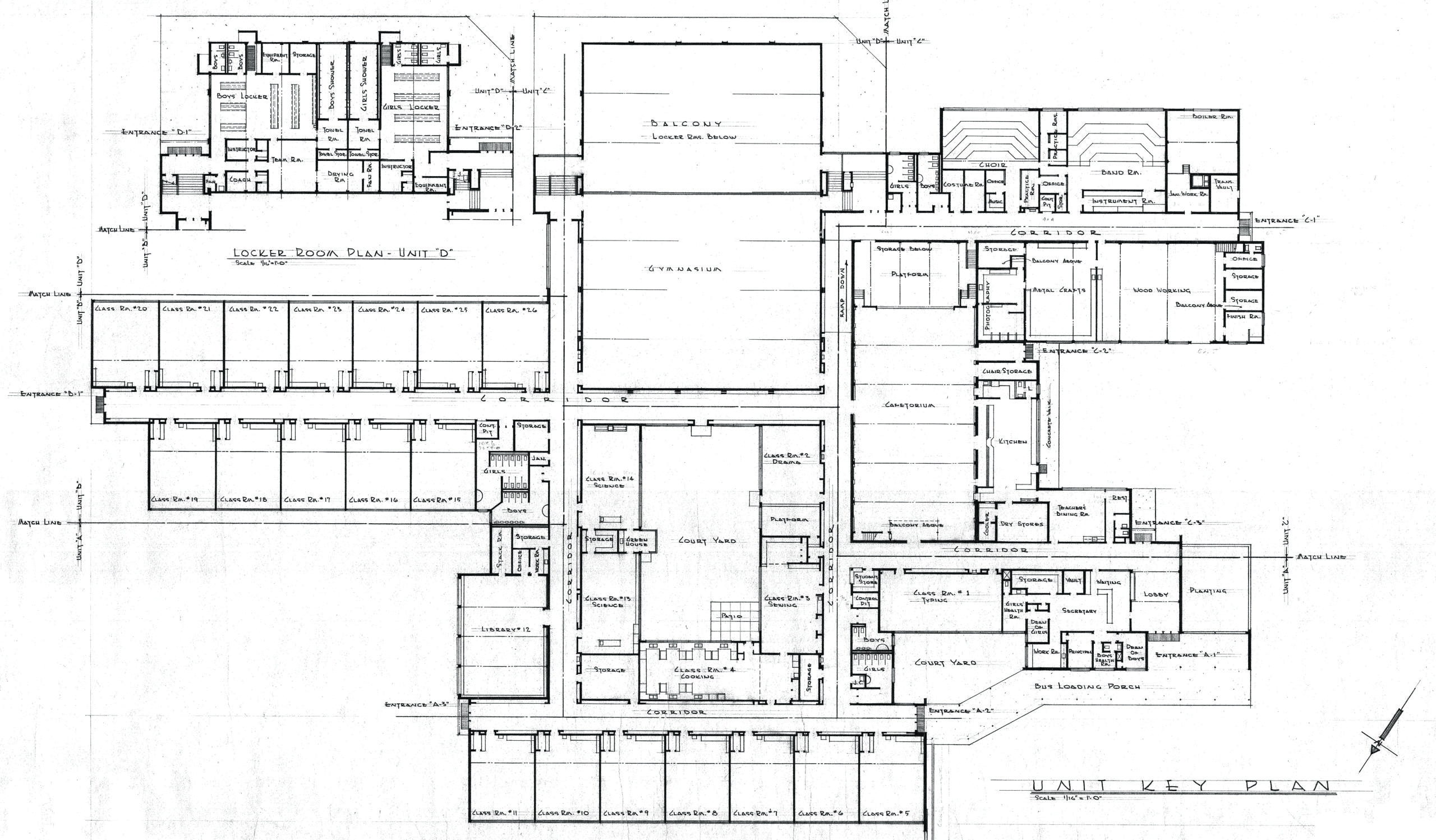

After World War II, schools stopped serving just the physical and educational needs of students but took interest in nurturing students’ emotional development. Schools of this era were typically long and low, one-story buildings designed in the International style with enormous windows, light-filled courtyards, and a decentralized floorplan.

According to mid-century educators, successful school planning required balancing three primary concerns: environment, education, and economy. The district needed to provide the best possible environment for students and teachers in order to facilitate learning while working within the limitations of the budget. [6] New schools had to meet both physical needs – sanitary, safe, quiet, well-lit – and emotional needs – pleasant, secure, inspiring, friendly, restful. In the Northwest, most schools reflected regional style by incorporating an interior courtyard. [7] During this period, the progressive theory of education was common. This theory was based on the concept that education should include the general welfare of students, not just their intellectual development, and that students should aspire to individuality not conformity. Teachers were encouraged to have a democratic classroom where they worked collaboratively with students rather than lecturing, and assignments were active and engaging rather than reading and watching. Additional topics were added to the curriculum that would better prepare students for the next phases in their lives, these topics included woodshop, home economics, and physical education. The general welfare of students was better minded and encompassed hot lunches, health services, and changes to disciplinary actions. [8]

The other hurdle for school districts was the rising cost of construction in the post-War era. For example, in 1930, $100,000 would buy a ten-room school, in 1940, it would buy an eight-room school and in 1950, it would buy a four-room school. [9] Fortunately for school district budgets, many communities wanted modern design schools rather than the neo-classical or art deco designs from previous decades, and these modern designs were less expensive to build. Mid-century schools and houses utilized new technologies, materials, and mass production methods to meet the demand for affordable and fast construction. [10] Classrooms also featured extensive built-ins that included sinks, slots for bulky roles of paper, and coat storage.

TYPICAL MID-CENTURY DESIGN ELEMENTS

Mid-century schools and suburban housing shared many design elements, including: floorplans laid out to maximize space and flexibility; floorplans, fenestration, and landscaping designed to create connections between indoor and outdoor spaces; facades featuring large windows and ribbon windows; buildings designed to accommodate easy expansion later; decorative elements replaced with contrasting wall materials on the exterior; floorplans encouraged socializing; single-story designs with flay or low pitch roofs and deep eave overhangs; and buildings integrated into the landscape. Mid-century schools featured larger sites and a greater emphasis on landscaping and outdoor recreation. This resulted in more sprawling school designs. Instead of compactly containing all school facilities within a single rectangular block, facilities were clustered by function, such as separating quiet classrooms from noisy cafeterias. Plans were often irregular.

Schools are designed from the inside out and what is on the inside reflects education theory and beliefs of the day. The next time you admire a school’s architecture, be sure to notice more than its visual aesthetic, but its role in the pursuit of education.

Written by Tricia Forsi, Preservation Planner.

Sources

[1] Donovan, John J. School Architecture: Principles and Practices. New York: MacMillan Company, p. 24

[2] Weisser, Amy S. “’Little Red School House, What Now?’ Two Centuries of American Public School Architecture.” Journal of Planning History. Vol. 5, No. 3. August 2006, p. 200

[3] Graham, Patricia Albjerg. Schooling America: How the Public Schools Meet the Nation’s Changing Needs. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 76-77

[4] Weisser 2006, 203

[5] Benjamin Fine, “Broader Vocational System Is Advocated to Help Meet Modern Industrial Needs,” New York Times, April 11, 1948.

[6] William W. Caudill, Toward Better School Design, New York: F. W. Dodge Corporation, 1954,

[7] Entrix, Inc., Portland Public Schools Historic Building Assessment, October 2009, p. 3-18

[8] “Modern Design Transforms Schools.” New York Times. August 24, 1952; “Modern Schools Are Built to Fit Child Emotionally and Physically,” New York Times, December 23, 1956; New Schools of Thought: Modern Trend in Education Is Reflected in Buildings Themselves,” New York Times, December 16, 1952; Abigail Christman, National Register of Historic Places Nomination: Colorado’s Mid-Century Schools, 1945-1970,” May 1, 2017

[9] “New Schools, U.S. Is Building Some Fine Ones But Is Facing A Serious Shortage.” Time. October 16, 1950, p. 80

[10] Otaga, “Building for Learning in Postwar American Elementary Schools.” p. 563.

At Peter Meijer Architect, PC (PMA), we integrate Design, Science, and Preservation. Founded in 2003, PMA provides our clients with professional architectural design, building envelope science, and preservation planning services throughout the Pacific Northwest with a core focus on existing and historic buildings.

At Peter Meijer Architect, PC (PMA), we integrate Design, Science, and Preservation. Founded in 2003, PMA provides our clients with professional architectural design, building envelope science, and preservation planning services throughout the Pacific Northwest with a core focus on existing and historic buildings.