Tropical Modernism was showcased, explored, and celebrated at the sixth annual Docomomo US National Symposium in late September 2019. Docomomo US/Hawaii chapter hosted, and as the current Docomomo US/Oregon chapter president I had the opportunity to experience all things tropical and modern in Oahu, Hawaii.

For those unfamiliar with the mouthful that is Docomomo (documentation for the conservation of the modern movement), it’s a national (technically international) non-profit dedicated to the preservation of modern architecture, landscape and design. At the Oregon chapter we take this mission a bit further by including art from the core era of modernism and one of the most controversial architectural movements: post modernism. But let’s get back to the oasis that is Oahu. First, if you have the opportunity to visit this island – DO IT. It is a multicultural, dense cosmopolitan city yet rural surf-town, absolute food heaven, post-war architectural wonderland where tropical resort design began, all rolled into one island that has weather far superior than what we ever get in the state of Oregon. Why do we all live in the cold and rain?!

The symposium kicked-off with a welcome reception at the Outrigger Canoe Club. The building is situated right along the Waikiki coast and was designed by Vladimir Ossipoff in 1941. Ossipoff had a prolific Honolulu-based firm, Ossipoff Snyder Architects. A common theme I was unware would take a central role throughout the symposium was about tropical outdoor/indoor living, or better known as lanai.

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII AT MANOA

University of Hawaii at Manoa hosted the first day of symposium presentations at Jefferson Hall. While there are several mid-century buildings across the campus, Jefferson Hall is an architectural gem among them. Completed in 1963 and designed by Chinese-American architect I.M. Pei with Young & Henderson. Jefferson Hall was the last building constructed of the East-West Center (EWC) campus. The EWC helped put Hawaii on an international stage, connecting Asia and the West. Jefferson Hall in particular “combines the austere symmetry of the New Formalism with hints of Chinese traditional architecture to convey the links between Asia and the West envisioned by the center’s multiple champions and founders.” (1.)

HAWAII OVERVIEW – from traditional architecture to mid-century modernism

Glenn Mason

Graham Hart

Bit perplexed that native Hawaiian architecture was breezed over and barely mentioned. The presentation began with thatched houses, then quickly jumped to the first Western-style frame houses being shipped to Hawaii in the 1820s. These were the type of structures the Missionaries were accustomed to. From there we learned that basalt quarries were developed in the 1880s, and the California Gold Rush really opened up west coast trade to Hawaii. For the first time Douglas Fir was shipped from the mainland to Hawaii. Mason then explained that while Hawaii had designers, they did not have architects, but architects from Australia or the mainland came to Hawaii and contributed to the beaux-arts and neo-classical styled structures. It wasn’t until the early 1900’s that a regional style began to express itself in Hawaii, and across the mainland. Hawaii regional style elements include: double pitched roof, lanai, local materials, and an overhang roof.

Towards the end of the 1930s change thinking happens and international style references begins to be expressed in architecture. Hawaii sees an influx of younger architects from Europe that were schooled in modernist design. The late 1930s had a stream of construction on military bases (several designed by Albert Kahns office), but by the time of WWII, 99% of architects on the island went to work for the military. From the 1930s through the 1960s there is a shift in the architecture vocabulary in Hawaii. It begins with regional style with a hint of modern, then modern used to reinterpret regionalism. Modern architects of note in Hawaii from that era:

Vladimir Ossipoff

Peter Wimberly

Lemmon, Freeth, Haines, and Jones

Edwim Bauer

Alfred Preis

Johnson & Perkins

The shift in the architecture vocabulary in Hawaii continues from the 1940s through the 1970s. Now we begin to see the environmental influences on modernism, even though rural landscapes are being transformed into cosmopolitan centers with smaller, steep, tight sites or housing. Materials used for modern design now includes concrete, cast concrete, lava rock, coral, local woods, and aggregates. Modern architecture in Hawaii also embraces the natural environment. This is most reflective in architect’s obsessions with lanai. This obsession found its way from residential homes to large developments. The East-West Center (1962-1963) at the University of Hawaii Manoa, designed by I.M. Pei, is a phenomenal example of a monumental, institutional piece of architecture that embraced the lanai.

ASIAN INFLUENCES

Alison Chiu and Alissa Carson

Lorraine Minatoishi

Luca Guido

This group of presentations focused on different facets of Asian influences and how the contributions were interwoven in post-war architectural design throughout Hawaii. Lorraine Minatoishi focused on Japanese temple architecture influence of modern design post-war. There were distinct temple styles developed throughout their history in Hawaii:

Japanese Traditional Style (late 1800s – early 1900s)

Plantation Style (late 1800s – early 1900s)

Hawaii Eclectic Style (early 1900s – 1950s)

East-West Style (1918 – 1950s)

Post-War Modernism (led by second-generation Japanese architect Niser)

Post-War Traditional

Luca’s presentation took it a step further by discussing an obscure architect from the mid-century modern era, Bruce Goff, and how he also influenced local architects to Hawaii. I had not heard of Bruce Goff like most, but Luca Guido explained why this figure in the realm of modernism was obscured until now.

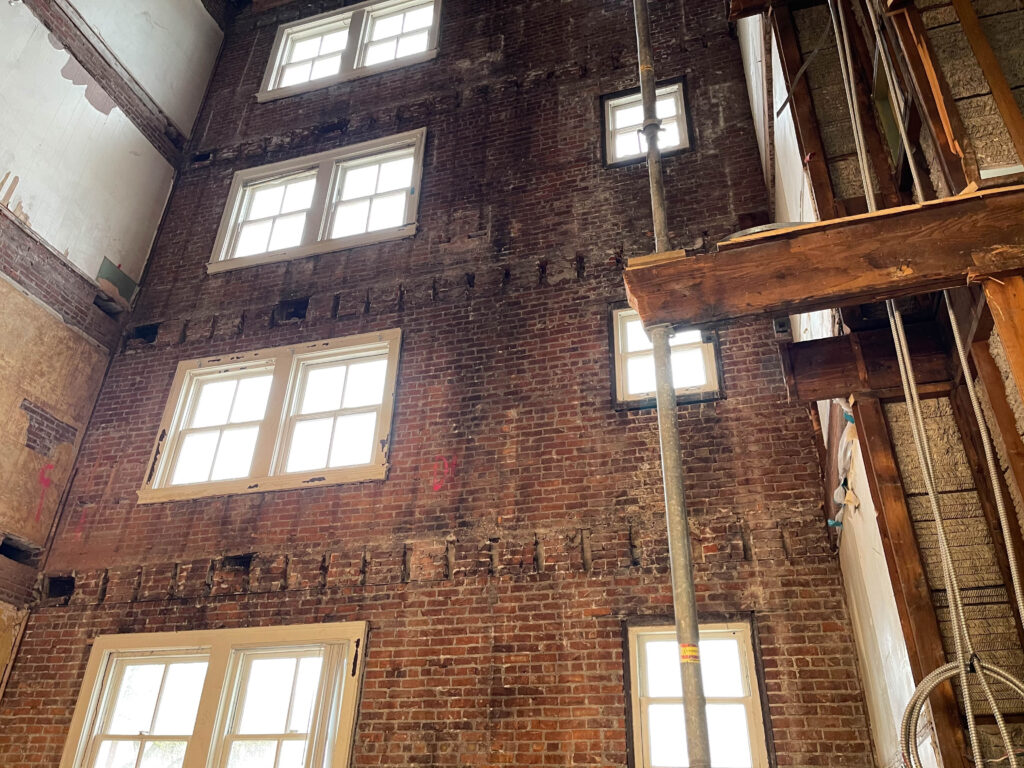

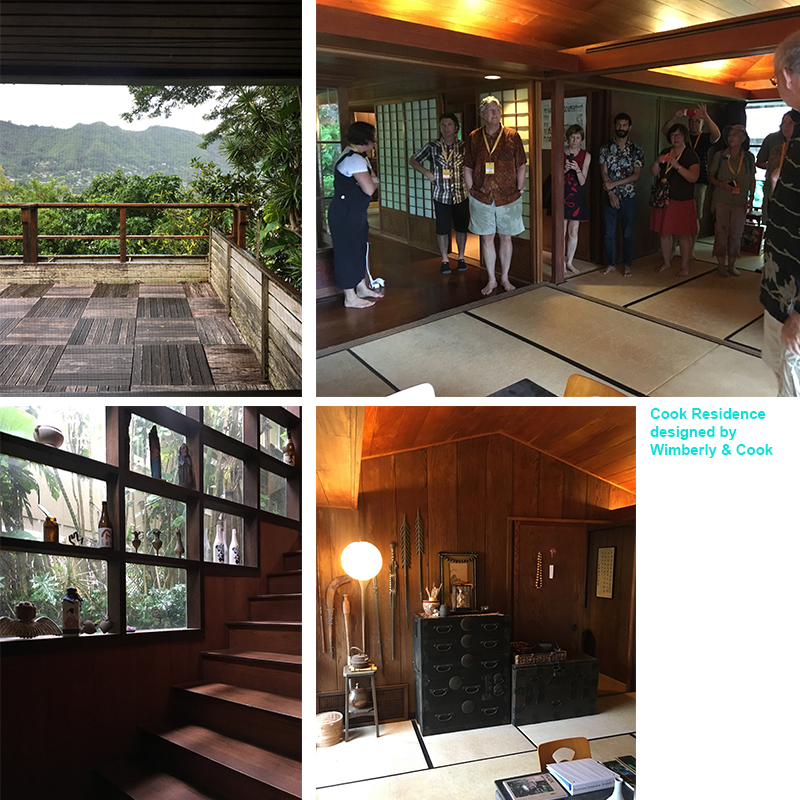

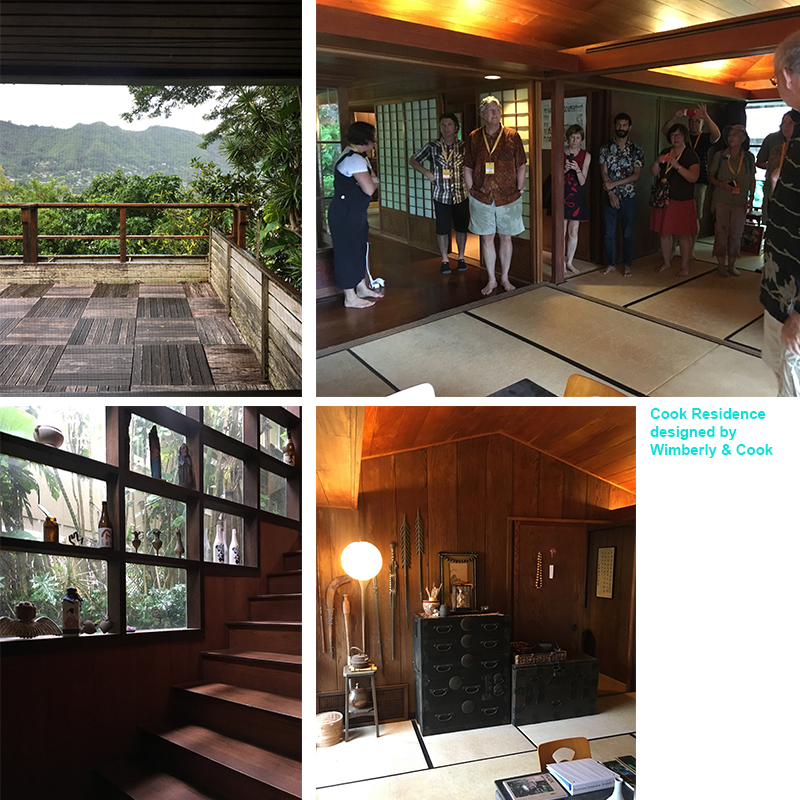

RESIDENCES OF WIMBERLY AND COOK

Following presentations at the University of Hawaii and a self-guided walking tour of other mid-century campus resources, I chose to attend the Residences of Wimberly & Cook Tour. Pete Wimberly of Wimberly & Cook designed two residences situated above the Manoa Valley. Wimberly designed some of the most iconic mid-century modern buildings in Hawaii. Wimberly came to Hawaii in 1940, and post-war his career flourished. His designs embodied tropical modernism, spaces that blurred indoor and outdoor living. The residential designs we toured both featured indoor/outdoor living, natural cross-ventilation, elegant interior details and finishes, and a smart use of natural light. However, they were completely different in essence, aesthetic, style, and state.

The Japanese style pavilion house was like walking into a meticulously cared-for time capsule. There wasn’t even dust on the book shelves that displayed artifacts collected and arranged by the original homeowner! However, there were a few signs of wear-and-tear on the interior Japanese style floor mats, kitchen cabinets along their frames, and slight dry-rot peppered across the original wood deck. Otherwise the home was pristinely maintained. Wimberly’s private residence across the street was a different story.

Wimberly’s private residence was constructed in 1945. This is an insane date for residential construction due to World-War II ending the same year, and the majority of architects/contractors in Oahu were working on military projects. With the Japanese style pavilion home, you enter by walking down slightly winding stone steps. With Wimberly’s private residence, you enter by climbing up stone steps that deliver visitors to a small landing, and then up more exterior stairs. The second set of stairs (wood planks suspended by cables) makes for a swoon-worthy entry sequence that looks like something Dwell or Architectural Digest would gobble up for a feature article.

From the now faded red door, redish-pink painted wood paneled ceilings, decorative animal sculptures situated within the header above the door that leads from the dining area into the kitchen, to ornate light fixtures and various metal finishes throughout the space, Wimberly’s private residence utilized design elements that reflected the multicultural diversity of Hawaii. The residence is also quintessential mid-century design: natural cross-ventilation, sliding wall panels to completely open up or section off the main-floor living, dining and lounge areas, and a technological savvy (for its time) kitchen. From the perspective of how we design kitchens today, it is real sad and small, save for the to-die-for view of the lush tropical garden from the kitchen window over the sink.

Wimberley’s private residence also showed signs of being well lived-in, yet not maintained with any desired vigor. The wood framed windows on either side of the structure are rotting like the planks along the entry façade deck, and there are several cracked panes of window glass. Structural settling has made itself known, and the kitchen is retro in a manner no one would want for daily use. Most of the interior painted walls or ceilings have faded into softer hues of their original bold colors. And, when we visited, it looked as though someone was living there, yet possibly setting up an estate sale for interior items. There were some true mid-century interior design gems scattered in the clutter piled up from the floor I wish I could have packed in my suitcase for the return trip.

Hope you enjoyed PART I: Tropical Modernism in a Multicultural Context at the Docomomo US National Symposium! In Part II we will discuss the Hawaii State Capitol, and presentations on Historic Preservation in Hawaii and Tropical Resort Design.

Written by Kate Kearney, Associate.

1. Shen, Haigo and Irene. Tropical Modernism At University of Hawaii At Manoa. Docomomo US National Symposium, Oahu, Hawaii, September 2019.