There are some instances when the English language enjoys sparking debate, confusion, and often apathy, look no further than the “10 items or less” vs. “10 items or fewer” conversation around the grocery check-out aisle. In the preservation field, we have our own niche conversation – the difference between the terms: preservation, rehabilitation, restoration, and reconstruction. Like with grocery store grammar, these four preservation terms hold undoubtedly different definitions and should be used correctly, but even when used incorrectly, we all still understand what you mean.

Let’s take a second a clarify what these four words do mean. As a preservationist, I turn to the source for these terms, the United States Department of the Interior.

Preservation is defined as the act or process of applying measures necessary to sustain the existing form, integrity, and materials of an historic property. Preservation, keeping a building at a particular moment in time.

Rehabilitation is defined as the act or process of making possible a compatible use for a property through repair, alterations, and additions while preserving those portions or features which convey its historical, cultural, or architectural values.

Restoration is defined as the act or process of accurately depicting the form, features, and character of a property as it appeared at a particular period of time by means of the removal of features from other periods in its history and reconstruction of missing features from the restoration period. Restoration, pin points a time in the building’s history and is accurate to only that time.

Reconstruction is defined as the act or process of depicting, by means of new construction, the form, features, and detailing of a non-surviving site, landscape, building, structure, or object for the purpose of replicating its appearance at a specific period of time and in its historic location. Reconstruction, recreates missing parts of a property through interpretation with plenty of research to back-up the choices.

PRACTICAL APPLICATION

I’ve found that the most common error is using preservation or restoration when the person almost always means rehabilitation. For me, much of my work focuses on rehabilitation, especially when a project seeks funding through local, state, or federal incentives like Historic Tax Credits. Aside from the definitions above, the most defining difference between preservation, restoration, and rehabilitation comes down to creative license.

When it comes to creativity and executing an artistic or architectural vision, rehabilitation is essentially synonymous with adaptive-reuse or repositioning. Rehabilitation, retains character but acknowledges a need for alterations in order to keep the property in use. When a building that was historically a school but is converted into a hotel or an office building becomes apartments, that’s rehabilitation. Even improving an existing use can be a rehabilitation project.

In the end, I like to associate each of these terms with what they will mean for their respective scope of work on a project. As mentioned, rehabilitation means a creative process that balances the historic character with modern needs. Preservation is essentially thoughtful maintenance so that the existing resource does not get wholly improved, but also is prevented from falling apart. Restoration and reconstruction are the most technically and scientifically involved requiring sufficient historic research and materials knowledge to justify the choices of retaining or rebuilding a resource. Unfortunately I don’t know of any mnemonic devise or other short cut to help clarify these four words, but hopefully a better understanding of their meaning will lead to fewer instances of their misuse.

Written by Tricia Forsi, Preservation Planner

Space programming respected the historic floor plan and scale of the original structure and recreated Yeon’s original design intent of integrating indoor space with outdoor space. Extraneous equipment and unsympathetic additions were removed from both the interior and exterior. Interior design elements, furniture, and fixtures maintain the open gallery spacial quality while integrating new furniture and fixtures meeting the needs of the tenant. Major preservation focused on the exterior restoring original paint colors through serration studies, restoring building signage in original type style and design, preserving original wood windows, when present, and restoring the intimate courtyard with a restored operating water feature.

Space programming respected the historic floor plan and scale of the original structure and recreated Yeon’s original design intent of integrating indoor space with outdoor space. Extraneous equipment and unsympathetic additions were removed from both the interior and exterior. Interior design elements, furniture, and fixtures maintain the open gallery spacial quality while integrating new furniture and fixtures meeting the needs of the tenant. Major preservation focused on the exterior restoring original paint colors through serration studies, restoring building signage in original type style and design, preserving original wood windows, when present, and restoring the intimate courtyard with a restored operating water feature. Moore, Lyndon, Turnbull & Whitaker’s 1965 Pavilion at Lawrence Halprin’s Lovejoy Fountain is a whimsical all wood structure with a copper shingle roof. Although a small structure, the pavilion represents a major mid-transitional work for Charles Moore as his design style moved from mid-century modern to Post-modern design. In keeping with the naturalistic design aesthetic established by Halprin, northwest wood species comprise the major structural system including the roof trusses, vertical post supports, and vertical cribs built from 2 x 4 members laid on their side and stacked.

Moore, Lyndon, Turnbull & Whitaker’s 1965 Pavilion at Lawrence Halprin’s Lovejoy Fountain is a whimsical all wood structure with a copper shingle roof. Although a small structure, the pavilion represents a major mid-transitional work for Charles Moore as his design style moved from mid-century modern to Post-modern design. In keeping with the naturalistic design aesthetic established by Halprin, northwest wood species comprise the major structural system including the roof trusses, vertical post supports, and vertical cribs built from 2 x 4 members laid on their side and stacked. The restoration approach is intended to correct the structural deficiencies and replace the failed members with no changes to the historic appearance of the structure. The crib design allows for insertion of new steel elements, invisible from the exterior, capable of providing additional support for vertical loads. The difficulty arises because standard wood products available today have different visible and strength attributes from standard components available in 1965. Sourcing appropriate lumber is dependent upon clear and quantifiable specification, high quality inspection, and visual qualities. There are no structural standards for reclaimed or recycled lumber compounding the incorporation of “old growth” lumber as part of a new structural system. When original source material is no longer available, best practices for narrowing the selection of new materials will of necessity be combined with subjective visual qualities and a best-guess scenario as to how the new material will age in place similarly to the historic material. There are no single solutions so experience is key.

The restoration approach is intended to correct the structural deficiencies and replace the failed members with no changes to the historic appearance of the structure. The crib design allows for insertion of new steel elements, invisible from the exterior, capable of providing additional support for vertical loads. The difficulty arises because standard wood products available today have different visible and strength attributes from standard components available in 1965. Sourcing appropriate lumber is dependent upon clear and quantifiable specification, high quality inspection, and visual qualities. There are no structural standards for reclaimed or recycled lumber compounding the incorporation of “old growth” lumber as part of a new structural system. When original source material is no longer available, best practices for narrowing the selection of new materials will of necessity be combined with subjective visual qualities and a best-guess scenario as to how the new material will age in place similarly to the historic material. There are no single solutions so experience is key. Case Study 3

Case Study 3

When replacement units are not required and the scope is limited to on-site repair, labor costs exceed material costs. Since many historic terra cotta units were specialty designed and installed for the structure, a premium price is paid for replacement. New exterior decorative terra cotta is available only from the sources referenced and with small quantity orders, the first unit is approximately $5,000 with much of the costs attributed to making the form and determining the finish color and texture. Subsequent costs per unit will decrease with the range of decrease dependent upon quantities required.

When replacement units are not required and the scope is limited to on-site repair, labor costs exceed material costs. Since many historic terra cotta units were specialty designed and installed for the structure, a premium price is paid for replacement. New exterior decorative terra cotta is available only from the sources referenced and with small quantity orders, the first unit is approximately $5,000 with much of the costs attributed to making the form and determining the finish color and texture. Subsequent costs per unit will decrease with the range of decrease dependent upon quantities required.

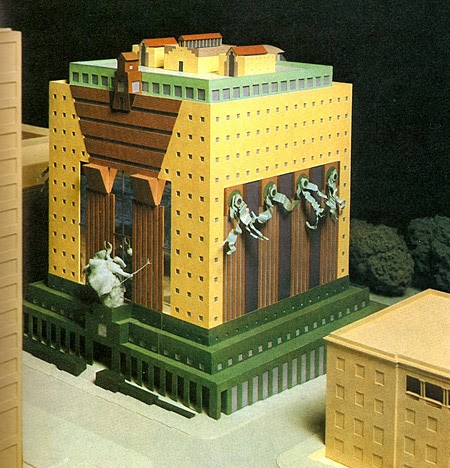

Creative, multi-jurisdictional, community involvement, private / public partnerships, government programs, and national and international marketing campaigns have become key elements to long range cultural resource management plans. The unique structures require innovative solutions matching the monumental character and commanding presence. Success stories abound from the saving of West Baden Springs Hotel in French Lick, Indiana to Centennial Hall in Wroclaw, Poland. The efforts to retain the giant structures are well deserved, because the continued loss of such buildings diminishes our understanding of world events.

Creative, multi-jurisdictional, community involvement, private / public partnerships, government programs, and national and international marketing campaigns have become key elements to long range cultural resource management plans. The unique structures require innovative solutions matching the monumental character and commanding presence. Success stories abound from the saving of West Baden Springs Hotel in French Lick, Indiana to Centennial Hall in Wroclaw, Poland. The efforts to retain the giant structures are well deserved, because the continued loss of such buildings diminishes our understanding of world events.