Part II of II guest blog post by Betsy Bradley, Historian and Historic Preservationist.

WHO IS THIS PUBLIC MEANT TO BE SERVED BY HISTORIC PRESERVATION?

While many can agree we need to involve the public in a meaningful way, we don’t often do so. But, who is the public we serve with public sector heritage work? The term public is left unqualified in most sections of the NHPA and 36 CFR 800. The phrase “general public” appears often, while “interested public” is used in sections referring to Tribal properties. Agencies are to seek and consider the views of the public and to consider the “likely interest of the public” in addressing effects to historic properties. In short, the regulations assume that the public will be notified and provided information about the identification and evaluation of historic resources and invites “the public to express views on resolving adverse effects.” How easily this process devolves into a Decides, Informs, Implements scenario with some paperwork.

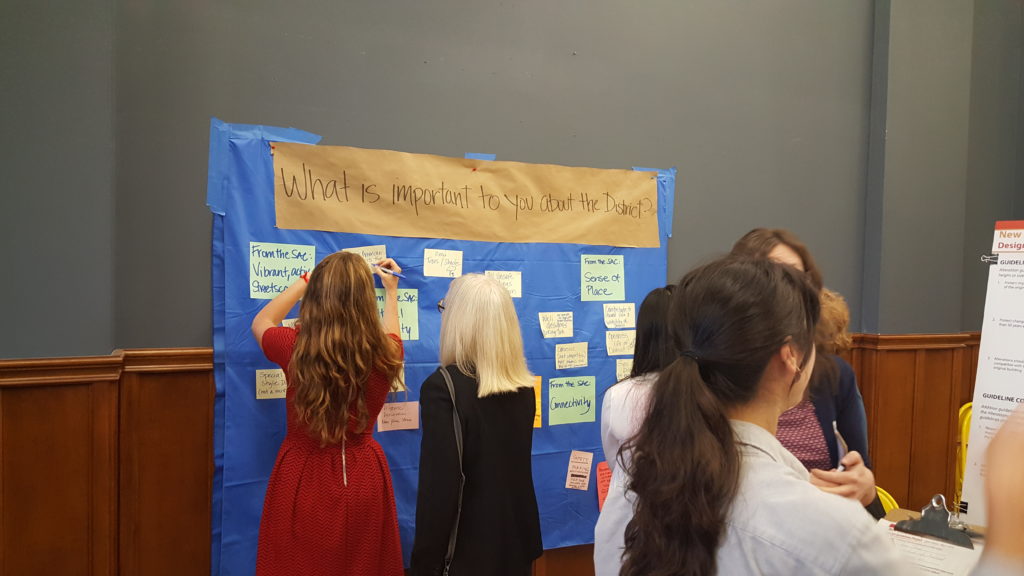

Consequently, we have the freedom to almost ignore the public even as we make the process somewhat transparent and provide information to those who ask. Conversely, we can identify various publics who could actively participate in the process and who can be involved in identifying and evaluating historic properties, as well as creating and using mitigation projects. We must go beyond the consideration of the public as the whole body politic, or all citizens.

Situational theorists working within the public relations field tell us there are three types of publics that have some interest and likely involvement in a topic or process, the:

1. Latent public becomes interested due to a certain project.

2. Aware public has interest in resources/topics before a project.

3. Active public is aroused to organization and action by a project.

I can easily further parse further the publics that we might serve as: the current public, future public, public affected by the undertaking, single-issue public, broader picture public, Historic Preservation public, and the general public. We must design consultation and mitigation projects to affect as many of these publics as we can, or have a good justification for serving a smaller segment of the public.

Currently, we act on the weak premise that—if some undefined member of the future public someday goes to the archives or museum storage facility and accesses documentation about a property that no longer exists—we are working in the public interest. However, we must note that the staff of the ACHP charged with the oversight of the Section 106 process has included in a policy statement that academia and academic associations are not considered to be “the public” for the purposes of the archaeological component of the Section 106 process. Even if this is not guidance that has widespread implementation, we must take this reading of the definition of the public to heart. It speaks to the need to serve more than one segment of the public.

My recent experience is that if authority is shared in the Section 106 process, it is likely that the public becomes problematic for bureaucrats. A portion of the affected and interested public in St. Louis faced with a large redevelopment project does not see history ending 50 years ago, the timeframe we use as for evaluating historic resources. This public saw the federal undertaking in the continuum of depriving African Americans of their neighborhoods that began with Urban Renewal and that remains unacknowledged. This public also did not separate history from activism; the insistence that our history project was totally separate from politically-charged protest of the use of Eminent Domain did not resonate. I find these points of view valid and worth taking to heart. The mitigation proposed by this public departed from the standard projects and some at the table were eager to dismiss them out of hand as not what we do. Even when part of this public participated in a public history project, some professionals wanted to control and approve of that work. Despite all this, a meaningful participatory public history project was completed.

The St. Louis project was a consultation process that exposed our inadequacy in consulting with the intent to respond to the affected public’s standpoints and recommendations for mitigation. We must learn how to respond differently to make affected publics valued partners in Section 106. It is us who must transform, not various publics, in order to share authority. My experience is that this will be both harder and more rewarding for all involved.

Will you be commit to a renewed effort to include various segments of the public in historic preservation consultation? What practice theories and methods can you bring to the conversation? Let’s work on this together.

FURTHER READING

Laurajane Smith coined the term authorized heritage discourse. Her Uses of Heritage (2006) and subsequent books and articles have been foundational in the Critical Heritage Studies field.

Randall Mason Mason has been a leader in decentering the physical attributes of resources in order to elevate the meaning and values we assign to resources. His important essay in Places, “Fixing Historic Preservation: A Constructive Critique of ‘Significance,’” is available here.

Jeremy Wells takes the position that our policies based on regulations cannot be adapted for more effective work; he also positions further study of historic preservation in social science research. Wells’ website Conserving the Human Environment, provides links to many of his papers. This link takes readers to the page where he explores Rebooting Environmental Compliance.

Author’s note: I am a historian and historic preservation who has had many seats at the historic preservation table, ranging from consultant to SHPO staff. I have recently undertaken a deep study of where we are in historic preservation and how we might practice in the field differently in the near future. The retrospective look that was taken at the 50th anniversary in 2016 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) provided a lot of dialog but no clear ways forward that are any different than what we have done in the past. Based on the assumption that there are additional effective practices we should explore, bolstered by a growing interest in Critical Heritage Theory, I’m convinced that we can add effective practices within the existing regulatory framework – particularly if we base them on more robust theories of historic preservation. Therefore, we have important work to do together to develop and apply practice theories for heritage work in the public sector. This essay is one of several that will explore how our practice can be different.

Author’s note: I am a historian and historic preservation who has had many seats at the historic preservation table, ranging from consultant to SHPO staff. I have recently undertaken a deep study of where we are in historic preservation and how we might practice in the field differently in the near future. The retrospective look that was taken at the 50th anniversary in 2016 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) provided a lot of dialog but no clear ways forward that are any different than what we have done in the past. Based on the assumption that there are additional effective practices we should explore, bolstered by a growing interest in Critical Heritage Theory, I’m convinced that we can add effective practices within the existing regulatory framework – particularly if we base them on more robust theories of historic preservation. Therefore, we have important work to do together to develop and apply practice theories for heritage work in the public sector. This essay is one of several that will explore how our practice can be different.