Photo by Charles Birnbaum courtesy The Cultural Landscape Foundation.

Public open spaces, especially urban open spaces, are coming into their own recognition as historic resources. They are receiving more attention because well-designed outdoor landscapes reflect our values as individuals and as a society. Though the way we use these spaces may shift over time, the designs still reveal our collective aspirations for our relationships with nature, the built environment, and with each other.

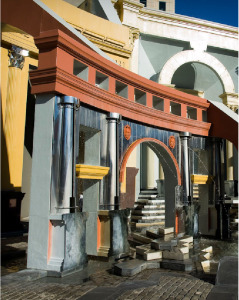

Two parkscapes in Portland are particularly good at showing us the values and aspirations of their era, and it is worth remembering the design concepts, and remembering how our interaction with the parkscapes has changed over time. These landscapes are the Washington Park Reservoirs, completed in 1894; and the SW Portland sequence of places anchored by Keller** and Lovejoy Fountains, completed in 1966-70.

Washington Park Reservoirs is a historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It was developed to store and distribute clean drinking water, but it had another important function which drove its design: it was a recreational destination for a growing urban population. At the end of the 19th Century, the City Beautiful movement across American cities inspired planners and politicians to create parks as refuges from urban life. Parks were seen as restorative, where citizens could breathe fresh air, stroll along paths or promenades, and view natural plants, lakes, and garden vistas. Many of our most famous American parks were developed during the City Beautiful era, including Central Park in New York City.

Washington Park and the Reservoirs were directly served by public transportation (the Portland cable car) and offered panoramic views east over the City towards the Cascade Mountains. The Reservoirs served as reflective focal points in a landscape designed to look completely natural, yet evoke romantic memories of western European aqueducts and fortresses.

By the 1930s, civic open spaces and the development of public parks had become unaffordable for most municipalities, and also had become less valued by Americans who were increasingly moving out of the cities and into suburban developments. Existing parks were generally not well maintained, and crime and vandalism created more abandonment by well-off city dwellers. By Mid-century, though, a new type of open space was being developed in many American cities. Under urban renewal programs, cities razed perceived decrepit, crowded, and crime-ridden neighborhoods and replaced them with open, clear, utopian style developments.

Portland Open Space courtesy TCLF

One of the largest and most successful Modern-era urban renewal projects in Oregon includes a series of public parks, walkways, fountains, and plazas designed by landscape architect Lawrence Halprin, known as the Halprin Open Space Sequence. The project, at the south end of downtown Portland, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2013. The Halprin nomination quotes from J. William Thompson, editor of Landscape Architecture magazine, comparing Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. (the progenitor of the City Beautiful movement) to Lawrence Halprin: “For Olmsted, the vision was one of pastoral relief from smoke and crowding; for Halprin, one of celebration of the city’s rambunctious vitality. Both viewed city parks and open spaces as a meeting ground for people of all classes.”

How much has our use of these two open spaces changed over time? We still get out of the house to walk in a park, possibly more than we did 50 years ago or 120 years ago. We have more leisure time, many of us own pets that need exercise, and people stay active longer than they used to. There have been societal changes that work against the popularity of local parks, including the ease of automobile transportation (pulling people further afield), the proliferation of other ways we can spend our leisure time, and the rise in obesity; but in general we use and care for our shared local parks and open spaces. However, there are changes in our relationships with these two specific open spaces that illuminate deeper trends in our society. One of the most complex relationship is the trend towards an increased mistrust of government.

The Washington Park Reservoir area shows the most profound shift in use over time. The need to cover and further protect drinking water in underground storage contains in lieu of open Reservoirs reflects a growing national divide between government and the public made visible by current limited access to a once prominent bucolic public destination. Perhaps a certain level of distrust is to be expected from decisions affecting public safety, but the potential loss of the Reservoirs as a contemplative, experiential destination is in stark contrast to the one of original design intent. Part of the current limited access results from the explosion in liability, where government agencies can and will be found at fault for any harm that might befall a park user or a water consumer. Federal regulations requiring municipal drinking water to be covered also feed our collective sense that there are malicious people among us.

The City of Portland is boldly attempting to both comply with the federal ruling to cover our drinking water reservoirs and restore the original city beautiful interaction with the park. In so doing, the City will eliminate the biggest concern with the liability and safety of our drinking water and the restorative design will re-imagine the Reservoirs, not as a highly urban, interactive series of features like the Halprin Sequence, but as a tranquil, even romantic, natural setting for the public to once again walk through and enjoy a natural beautiful city.

Amazingly, the Halprin Open Space Sequence continues to survive the “age of liability” with its wonderful interactive fountains, plazas, and pools intact. Nothing this fun- and potentially hazardous- will likely be constructed again as a public project. The design reminds us that we must be responsible for protecting this level of freedom, and that this very public- and yes, democratic- open space, is uniquely valuable as a symbol of public trust.

Written by Kristen Minor, Preservation Planner

Washington Park Reservoirs is a historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It was developed to store and distribute clean drinking water, but it had another important function which drove its design: it was a recreational destination for a growing urban population. At the end of the 19th Century, the City Beautiful movement across American cities inspired planners and politicians to create parks as refuges from urban life. Parks were seen as restorative, where citizens could breathe fresh air, stroll along paths or promenades, and view natural plants, lakes, and garden vistas. Many of our most famous American parks were developed during the City Beautiful era, including Central Park in New York City.

Washington Park Reservoirs is a historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It was developed to store and distribute clean drinking water, but it had another important function which drove its design: it was a recreational destination for a growing urban population. At the end of the 19th Century, the City Beautiful movement across American cities inspired planners and politicians to create parks as refuges from urban life. Parks were seen as restorative, where citizens could breathe fresh air, stroll along paths or promenades, and view natural plants, lakes, and garden vistas. Many of our most famous American parks were developed during the City Beautiful era, including Central Park in New York City.

The Washington Park Reservoir area shows the most profound shift in use over time. The need to cover and further protect drinking water in underground storage contains in lieu of open Reservoirs reflects a growing national divide between government and the public made visible by current limited access to a once prominent bucolic public destination. Perhaps a certain level of distrust is to be expected from decisions affecting public safety, but the potential loss of the Reservoirs as a contemplative, experiential destination is in stark contrast to the one of original design intent. Part of the current limited access results from the explosion in liability, where government agencies can and will be found at fault for any harm that might befall a park user or a water consumer. Federal regulations requiring municipal drinking water to be covered also feed our collective sense that there are malicious people among us.

The Washington Park Reservoir area shows the most profound shift in use over time. The need to cover and further protect drinking water in underground storage contains in lieu of open Reservoirs reflects a growing national divide between government and the public made visible by current limited access to a once prominent bucolic public destination. Perhaps a certain level of distrust is to be expected from decisions affecting public safety, but the potential loss of the Reservoirs as a contemplative, experiential destination is in stark contrast to the one of original design intent. Part of the current limited access results from the explosion in liability, where government agencies can and will be found at fault for any harm that might befall a park user or a water consumer. Federal regulations requiring municipal drinking water to be covered also feed our collective sense that there are malicious people among us.  Amazingly, the Halprin Open Space Sequence continues to survive the “age of liability” with its wonderful interactive fountains, plazas, and pools intact. Nothing this fun- and potentially hazardous- will likely be constructed again as a public project. The design reminds us that we must be responsible for protecting this level of freedom, and that this very public- and yes, democratic- open space, is uniquely valuable as a symbol of public trust.

Amazingly, the Halprin Open Space Sequence continues to survive the “age of liability” with its wonderful interactive fountains, plazas, and pools intact. Nothing this fun- and potentially hazardous- will likely be constructed again as a public project. The design reminds us that we must be responsible for protecting this level of freedom, and that this very public- and yes, democratic- open space, is uniquely valuable as a symbol of public trust.