DOCOMOMO_OREGON and the Northwest Chapter of the Association for Preservation Technology recently held an Energy Conservation Symposium that explored issues facing mid-century modern buildings: How can modern historic buildings comply with today’s energy conservation standards? Is it possible to maintain the integrity of the historic building materials and aesthetics while also meeting new energy conservation requirements?

At PMA we believe that while challenging, it is possible to maintain the integrity of these historic mid-century modern buildings and meet new energy conservation requirements. In an effort to explore this possibility, we submitted an abstract for the symposium, and Halla Hoffer, AIA, subsequently presented on Best Practices for Providing Effective Daylight in Mid-Century Modern Structures.

BACKGROUND

Effective daylighting can reduce both lighting and cooling loads while improving user comfort, satisfaction, and health. Despite plentiful glass, using daylight in mid-century modern building can be challenging. Glare and uneven light distribution can cause user discomfort and pose challenges to effectively daylighting spaces. Frequently, artificial lighting is used to balance lighting in spaces over lit by the sun, negating any potential energy savings. For existing buildings, the available methods to provide effective daylighting are limited by the existing constructions and configuration. To both preserve existing structures and provide ample daylight a critical question must be answered – what are the best practices for improving daylight in existing buildings? This study provides insight to daylighting existing structures, specifically, how light can be controlled and distributed in mid-century modern buildings with plentiful glazing.

1963 RESIDENTIAL TOWER

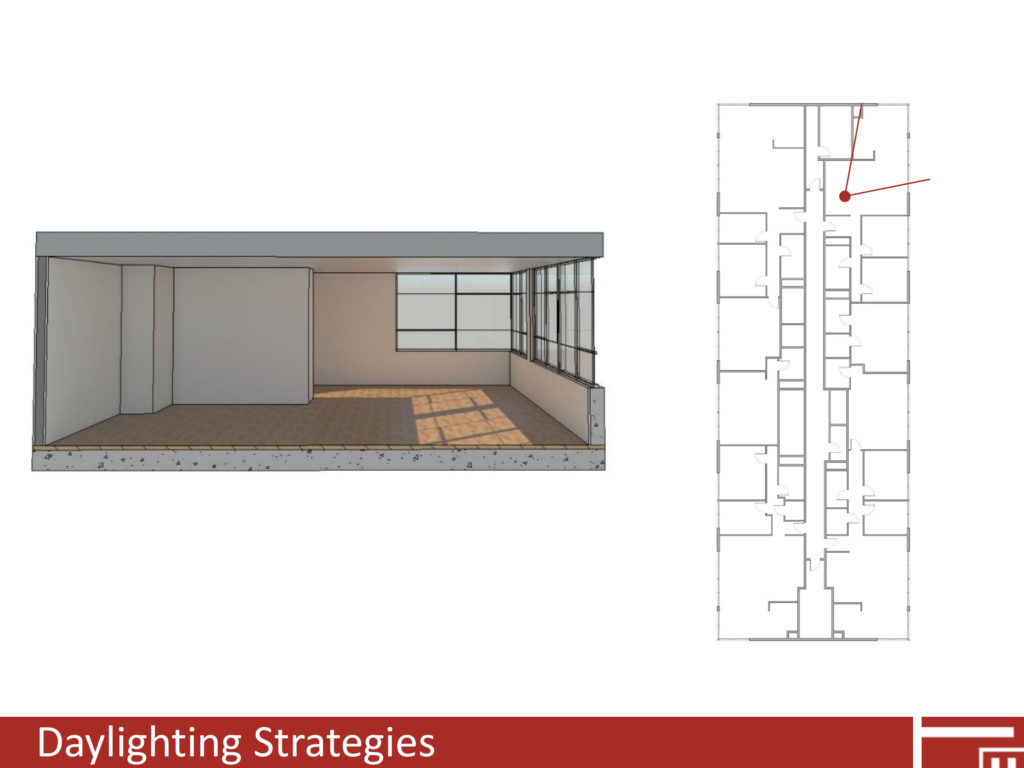

This study explores and analyzes how common daylighting strategies can be implemented on existing mid-century modern structures. The study focuses on a sixteen-story 1963 residential tower in Portland, Oregon, and explores how interior reflectivity, interior/exterior light shelves, shading, and glazing can impact daylight availability and distribution. The study looks at a variety of ways each strategy can be implemented and analyzes the results to determine best practices based on daylight distribution/availability, glare, lighting loads, and heating/cooling loads.

TOOLS USED FOR SPECIFIC ANALYSIS

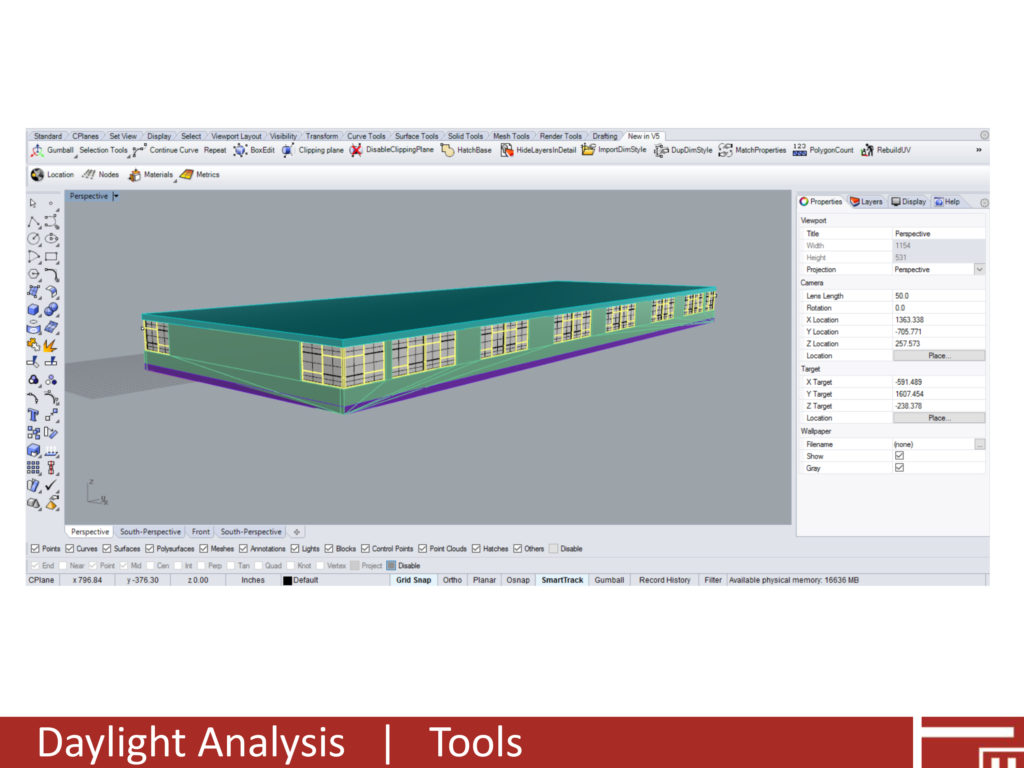

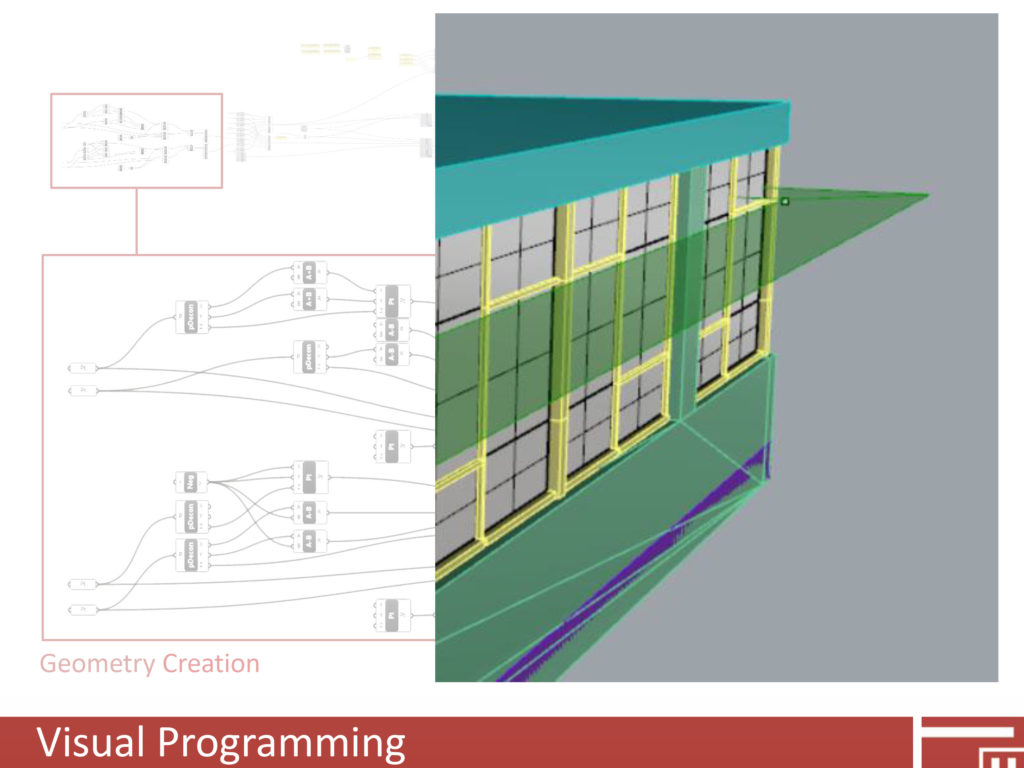

Emerging tools and technologies provide effective methods of analyzing hundreds of different daylighting simulations. Applications such as Grasshopper and Dynamo, which are visual programming environments for Rhinoceros 3D and Revit respectively, allow users to explore a variety of different design interventions and determine optimal solutions. Prior to starting the daylight analysis, we began with a “base geometry” of the existing conditions that we modeled in Rhinoceros 3D. We then developed a Grasshopper file to create daylighting interventions. For this study the interventions consisted of interior light shelves and exterior shading devices based on numerical inputs for shelf depth and height. Using Grasshopper in lieu of traditional 3D modeling allowed us to systematically test multiple variations of intervention geometry. In addition to studying how new geometries would impact daylighting we also studied how existing/new materials could impact daylighting performance.

The daylighting analysis was performed using DIVA for Rhino, a plug-in that performs daylighting and energy analysis directly in Rhino. DIVA also offers several Grasshopper nodes, allowing the analysis to be controlled and managed directly in Grasshopper. For this analysis the primary results we extracted and used to measure performance included:

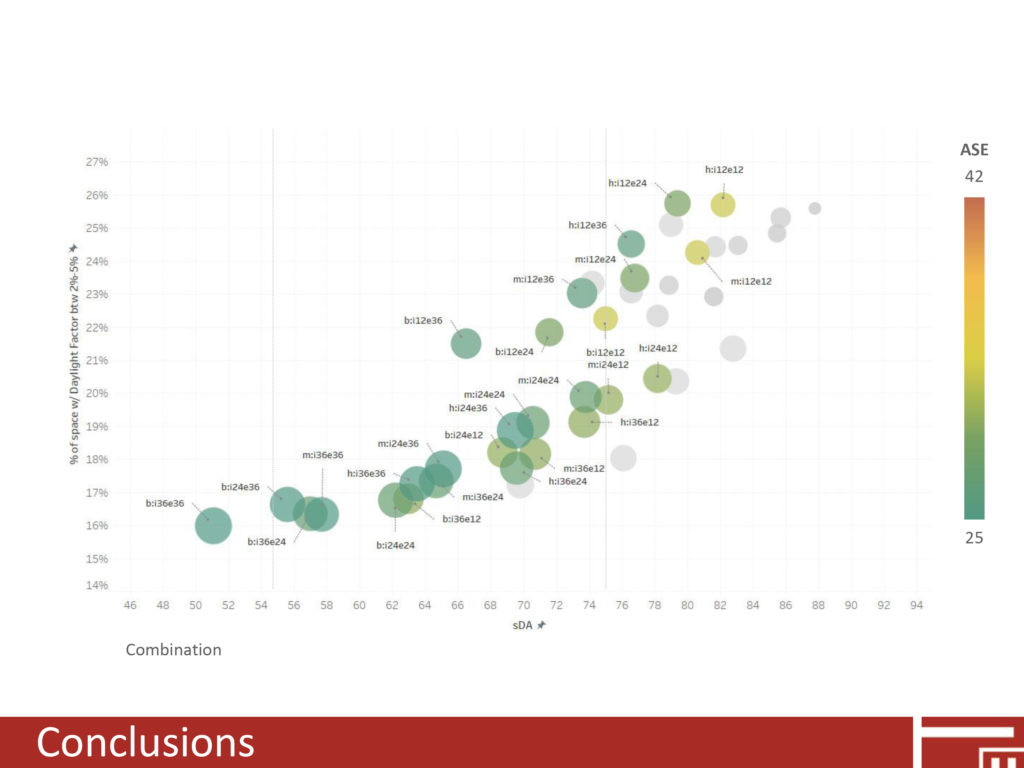

CONCLUSIONS

Reflective interior surfaces can have a significant impact on daylight distribution.

Without any shading there is a high probability for glare according to ASE and DF values.

Interior light shelves alone can reduce the ASE values and the probability of glare.

Interior light shelves alone are not as effective as exterior shading devices in reducing glare.

A combination of reflective interior materials, interior light shelves, and exterior shading devices is the most effective method to provide adequate levels and even distribution of light.

Written and presented by Halla Hoffer, AIA, Assoc. DBIA / Associate

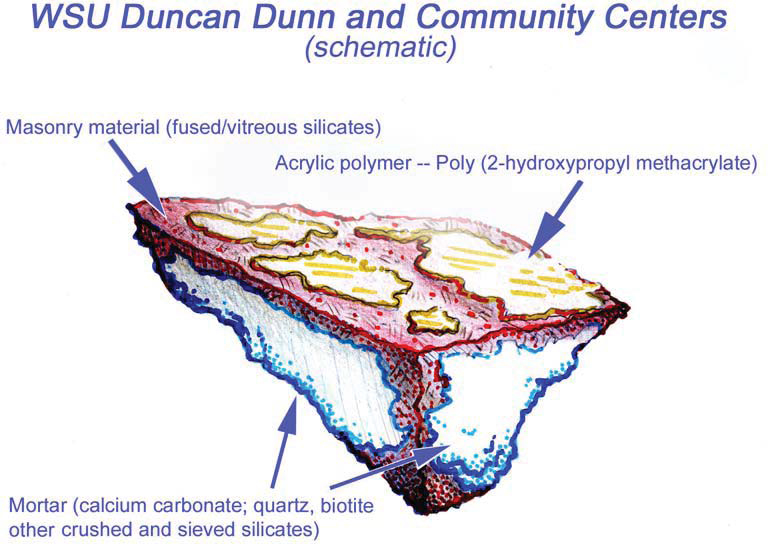

Believing the white haze was a result of UV degradation of a masonry sealer, PMA conducted Reunion Internationale des Laboratoires D’essais et de Recherches sur les Materiaux et les Constructions (RILEM) tube tests of water absorption on the exterior brick on Duncan Dunn Hall. The area of brick chosen for the test was out of direct sunlight to avoid affecting the results and was conducted during dry weather. No movement of the water over a 45 minute period was recorded during the test. Masonry units, even those constructed with high quality clays under controlled firing conditions will absorb some water. The results of the field test on Duncan Dunn, along with the white surface haze, reinforced the assumption of the presence of a masonry coating.

Believing the white haze was a result of UV degradation of a masonry sealer, PMA conducted Reunion Internationale des Laboratoires D’essais et de Recherches sur les Materiaux et les Constructions (RILEM) tube tests of water absorption on the exterior brick on Duncan Dunn Hall. The area of brick chosen for the test was out of direct sunlight to avoid affecting the results and was conducted during dry weather. No movement of the water over a 45 minute period was recorded during the test. Masonry units, even those constructed with high quality clays under controlled firing conditions will absorb some water. The results of the field test on Duncan Dunn, along with the white surface haze, reinforced the assumption of the presence of a masonry coating.