Buildings are physical representations of the social, economic, political, technological, and cultural climates of their eras of origin. Ultimately buildings represent our cultural heritage and our architectural history. However, mid-century modern era buildings are increasingly interpreted as antiquated architecture that is functionally obsolete and lacking use in today’s society. Our recent-past modern buildings are being labeled as “failed” or “useless” architecture. As a result, mid-century modern architecture is rapidly being demolished and replaced with newer sustainable structures believed to better represent our most current social and cultural ideals. Current architecture is believed to be far more aesthetically pleasing than their modern predecessors.

But in the context of society, including heritage, what constitutes “useful” architecture verses useless building? There must be a relationship of parts to complete the building, but structure and function alone do not equate to architecture. Perhaps “useful” should be a term connected to architecture exhibiting enduring design excellence? Paradoxically, design excellence is tangled with style, and history demonstrates that style preference is ephemeral, subjective, and fluxuates at a high velocity. Yet the loss of style preference, or the falling out of design aesthetics favor, is one of the biggest rationale for the demolition of modern era buildings. Presently, Brutalism is at the crux of the demolition/ preservation debate.

Framed in the context of history, it can only follow that Brutalist buildings were going to be executed as formal monumental concrete structures that directly juxtapose (even challenge) their environments. But more often than not, the perspective of historic context is outnumbered by present aesthetic preference. For example, Prentice Women’s Hospital (Bertrand Goldberg) in Chicago, the Berkeley Art Museum (Mario Ciampi) in California, and several of Paul Rudolph’s brute beauties were technological and architectural triumphs of their time. However, the Brutalist buildings like other modern era buildings that rate low on the aesthetic-scale have been equally disregarded in their maintenance. The argument for demolition based on deficiencies caused by a lack of maintenance becomes all too convenient. The wide-spread demise of brutalist civic and urban buildings is a demise of the ideologies behind the intent of the architecture and those housed within.

Aesthetics cannot be the pretext for significance or the preservation of architecture. Letting aesthetics judge value will strip our architectural history of some of the most influential and innovated examples of modern era architecture. In effect, we are killing, and ultimately denying claim to, a portion of our architectural history. There is value in the perspective of context and value in re-using and re-imagining modern era architecture. If aesthetic preference continues to get in the way, what use is there for the architect or an architectural legacy?

Written by Kate Kearney, Marketing Coordinator

For more information about this exciting project, including a list of buildings for intensive research, mid-century modern properties, city map with property locations, and property descriptions. Visit:

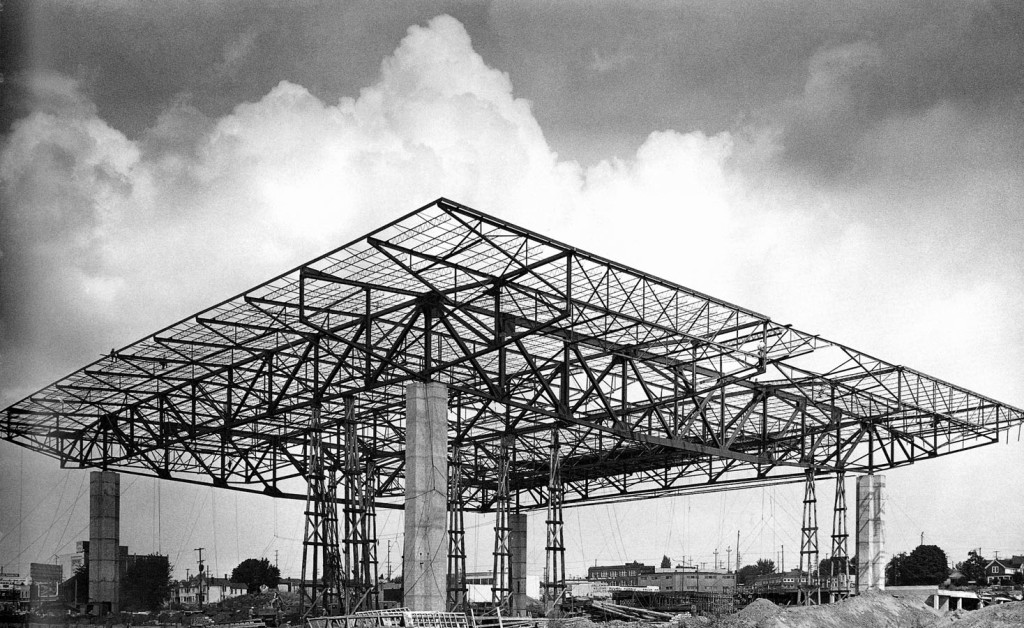

For more information about this exciting project, including a list of buildings for intensive research, mid-century modern properties, city map with property locations, and property descriptions. Visit:  Many of Portland’s iconic landmark buildings are modern era resources, such as the Veterans Memorial Coliseum, Lloyd Center Mall, U.S. Bancorp tower, and the Portland Building. The survey intentionally excludes these well-known properties in order to highlight broader architectural patterns and identify some of the less prominent buildings that may be considered historically significant in the future.

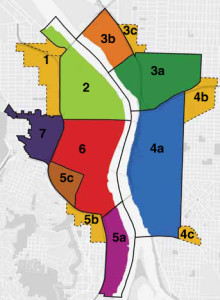

Many of Portland’s iconic landmark buildings are modern era resources, such as the Veterans Memorial Coliseum, Lloyd Center Mall, U.S. Bancorp tower, and the Portland Building. The survey intentionally excludes these well-known properties in order to highlight broader architectural patterns and identify some of the less prominent buildings that may be considered historically significant in the future. Of approximately 976 modern period resources within the Central City’s seven geographic clusters, PMA selected 152 properties for reconnaissance level survey. Representation of geographic clusters, resource typologies, and potential eligibility were considered when selecting properties to survey. In a selective survey, most properties should be considered potentially eligible for historic designation. Online maps, tax assessor information, and Google Earth were used to inform the selection process. Fieldwork involved taking photographs of each property, recording the resource type, cladding materials, style, height, plan type, and auxiliary resources, and then making a preliminary determination of National Register eligibility based on age, integrity, and historic character-defining features. A final report outlines the project and findings, and survey data was added to the Oregon Historic Sites database.

Of approximately 976 modern period resources within the Central City’s seven geographic clusters, PMA selected 152 properties for reconnaissance level survey. Representation of geographic clusters, resource typologies, and potential eligibility were considered when selecting properties to survey. In a selective survey, most properties should be considered potentially eligible for historic designation. Online maps, tax assessor information, and Google Earth were used to inform the selection process. Fieldwork involved taking photographs of each property, recording the resource type, cladding materials, style, height, plan type, and auxiliary resources, and then making a preliminary determination of National Register eligibility based on age, integrity, and historic character-defining features. A final report outlines the project and findings, and survey data was added to the Oregon Historic Sites database.