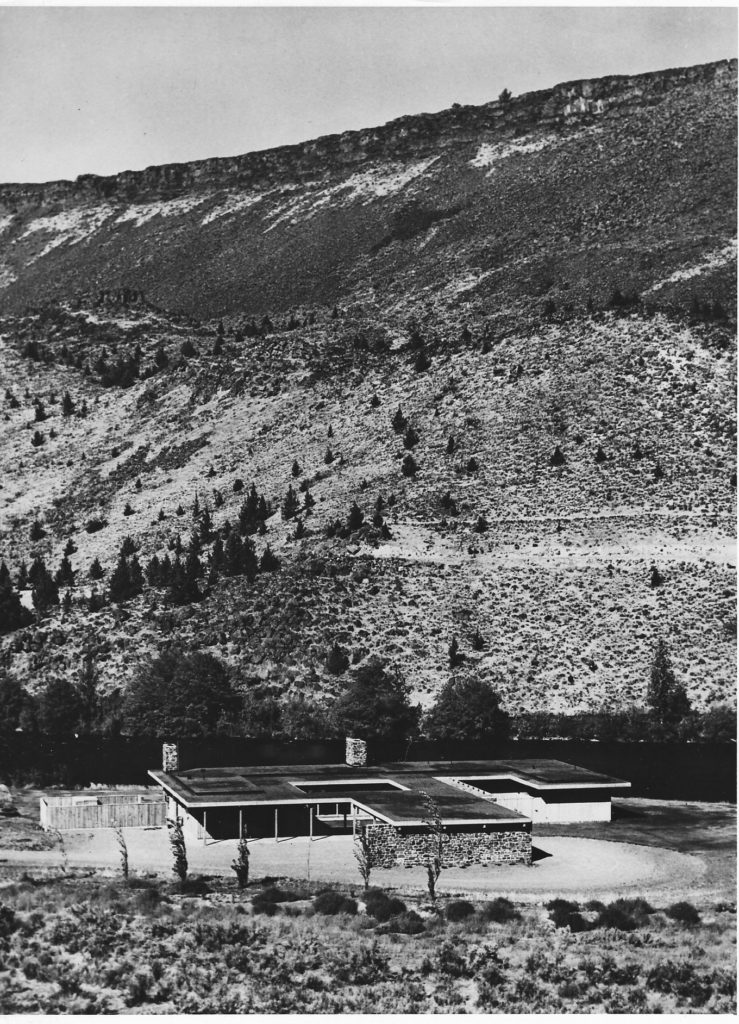

This fall, Halla Hoffer, AIA, Assoc. DBIA and Peter Meijer, AIA, NCARB, had the opportunity to teach a course in the Historic Preservation Program at the University of Oregon, School of Architecture & Allied Arts: Field Recording Methods. The course is designed for students to learn and practice the methods and strategies for conducting physical site, structure, building, and object investigation using professional practice standards. The case study for learning these methods and strategies included the Belluschi designed Robert and Charles Wilson Homes situated along the Deschutes River. The homes are included in Restore Oregon’s 2019 Most Endangered Places list.

1. How does your architect’s mindset influence your role teaching a historic preservation class?

Historic Preservation and Architecture are very closely tied together – and yet there can be a disconnect between the two fields. As architects, we are taught to think creatively about problems and develop design solutions, while also understanding building constructions and materials. I believe our background in architecture gives us a unique perspective on not only on the construction of historic buildings but also allows us to creatively find ways to preserve those structures. In this course, we’ve been able to share our architectural experience through discussions on building observations/assessment, drawing conventions, building materials, and more.

2. What is your favorite aspect of working with students interested in learning about how to conduct site-specific observation/assessments for historic structures?

We’ve had the opportunity to take two field trips out to the Wilson Homes in Warm Springs, Oregon. Each visit has been a really fun experience for the entire class. When learning how to conduct a building assessment – there is only so much information that can be communicated through a lecture. The experience of being in the field and observing a structure in person cannot compare to photographs. I’ve had a lot of fun looking at the Wilson Homes with the class – and making observations with them about the condition of the homes, original constructions/materials, existing conditions, etc.

3. Do you have a favorite aspect of the Belluschi designed Wilson Homes? [layout; relation to the land; opportunity for rehab; etc…]

One of the most unique aspects of the Wilson Homes is their location on the Deschutes River. The homes are located directly on the river – and deeply connected to the landscape. It is difficult to explain the experience of being within a canyon along the Deschutes River and within one of the Wilson Homes. The views and sounds of the landscape are completely intertwined with the experience of the Homes.

4. Why is it important to rehabilitate these structures? What stories will be lost if they disappear?

Few intact examples of northwest mid-century modern homes remain. As a culture – our preferences for interior finishes, appliances, spatial layouts, etc have changed over the last half-century. Many mid-century homes have retained their exterior appearance, yet significant interior alterations have altered the original design intent. The Wilson Homes are unique in that minimal interior renovations have taken place. In both homes, the original spatial arrangements remain in-tact and many of the finishes are unaltered. The Robert Wilson home is particularly unique in that the original kitchen remains, dishwasher included. A rehabilitation would preserve these unique examples of mid-century architecture in the Pacific Northwest.

5. If you could give one piece of advice to graduate students (or recent graduates), what would it be?

Take the time to form relationships with both professors and people outside of school you can learn from. School is a wonderful, structured way to gain knowledge. But… that structure falls away once you graduate – and the need to continue learning doesn’t. Having people you can reach out to for guidance can be a valuable tool!

Halla Hoffer, AIA, Assoc. DBIA

Associate / Peter Meijer Architect, PC

Halla is passionate about rehabilitating historic and existing architecture by integrating the latest energy technologies to maintain the structures inherent sustainability. Halla joined PMA in 2012 and was promoted to Associate in 2016. She is a specialist in energy and environmental management, as well as building science performance for civic, educational, and residential resources. Halla meets the Secretary of the Interior’s Historic Preservation Professional Qualification Standards (36 CFR Part 61).

Halla is passionate about rehabilitating historic and existing architecture by integrating the latest energy technologies to maintain the structures inherent sustainability. Halla joined PMA in 2012 and was promoted to Associate in 2016. She is a specialist in energy and environmental management, as well as building science performance for civic, educational, and residential resources. Halla meets the Secretary of the Interior’s Historic Preservation Professional Qualification Standards (36 CFR Part 61).