BACKGROUND

Construction means and methods of masonry veneer walls, and particularly flashing systems needed for protection from water intrusion of those veneer walls, was well known in the Post-Modern era (circa 1980’s – 1990’s). Many professional organizations and industries (e.g. Brick Institute of America) published technical documents as guides to proper construction of masonry veneer walls.

PMA was retained to conduct a building envelope enclosure assessment of a Post Modern masonry veneer building, over the Owner’s concern of advanced deteriorated conditions of precast window sills. The purpose of the assessment was to provide the Owner an understanding of the extent of the precast failures, whether or not any other materials were impacted by the failed conditions, and to provide an analysis of potential cause and a rough order of magnitude cost of potential mitigation. The Owner also sought an evaluation of the effectiveness of a proposal to install sheet metal over the sills to prolong the life of the precast for another forty years.

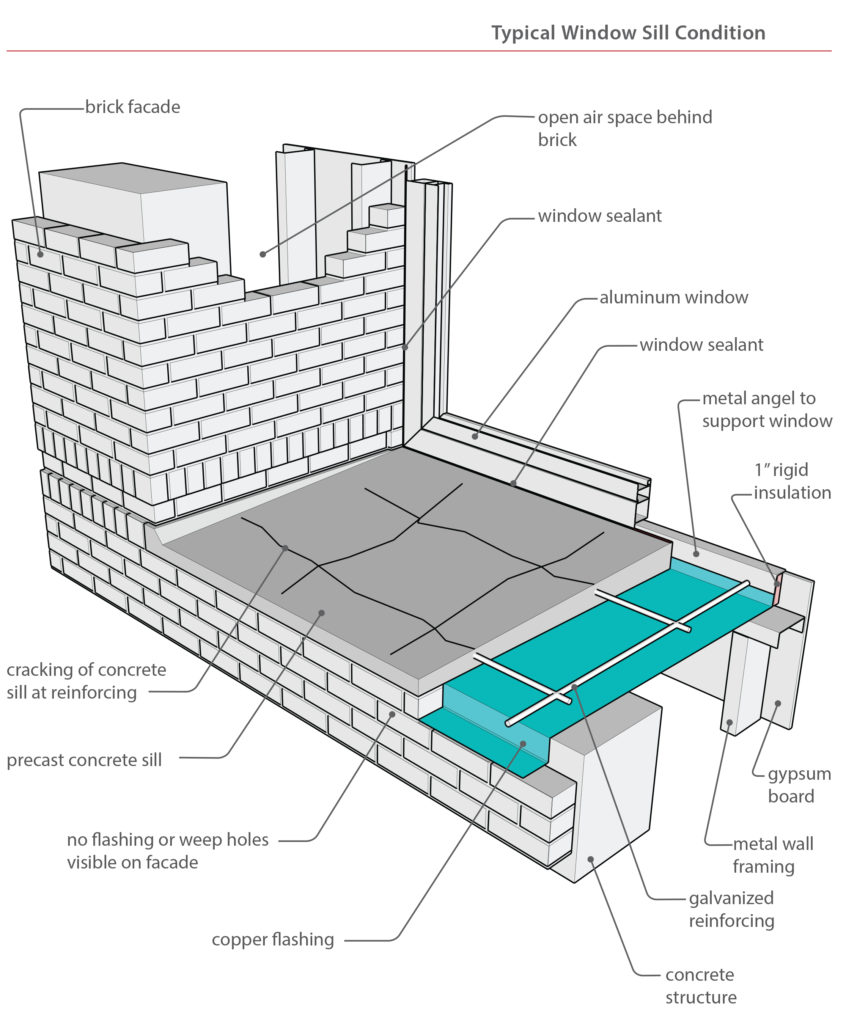

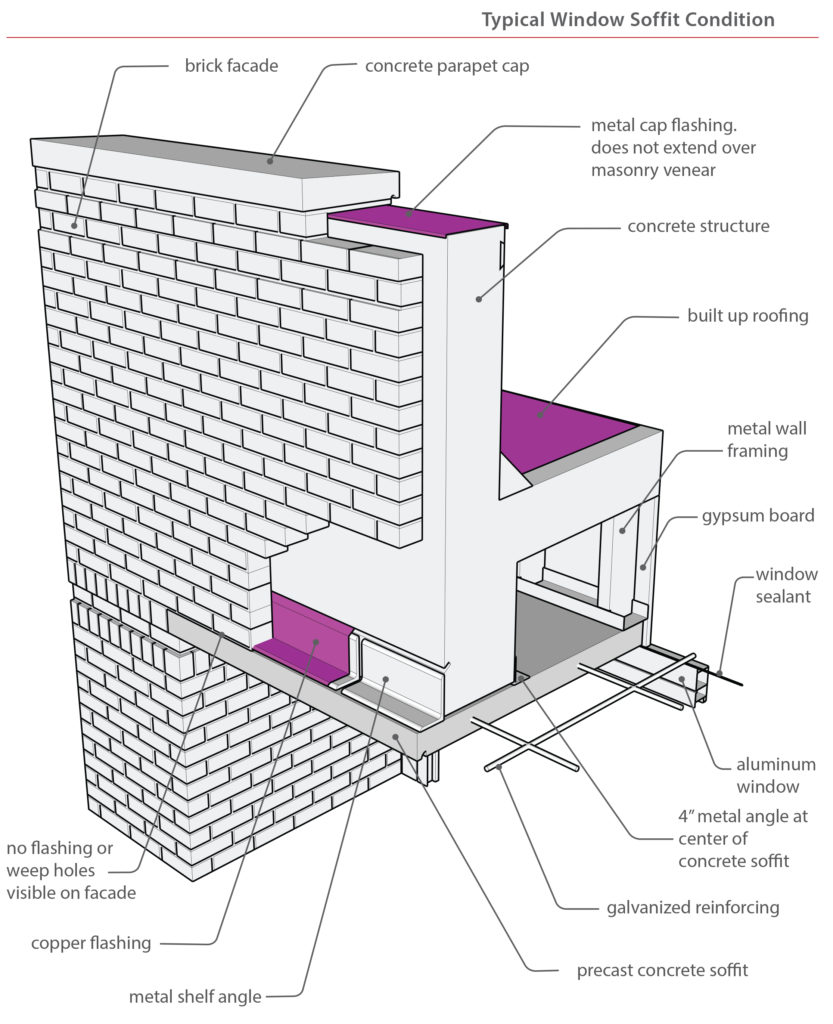

The circa 1984 Post Modern masonry veneer building links two existing historic academic classroom buildings and functions as both laboratory space and faculty offices. The building is an off-set “T” in plan with the leg of the T forming the link between the existing academic structures. A six-story faculty office tower, rises between the existing structures on the east end of the leg. The majority of the window openings occur along the bar of the T on the west elevation. The building wall cross section, from exterior to interior, is comprised of a single course of masonry veneer, a 1.5 inch air gap, an 12 inch thick cast in place concrete structural frame, a 4 inch air gap, steel stud framing, and one layer of interior gypsum board. Given the laboratory program, there is a strong interior positive air pressure that creates significant air flow within the interior air gap between the gypsum board and concrete frame. There have been no major renovations of the building since its construction.

ASSESSMENT PROCESS

PMA conducted a two-part assessment program. Part 1 consisted of a visual only assessment performed on the precast window sills, precast window headers, masonry veneer mortar joints, sealant joints, and interior gypsum board adjacent to the aluminum window sill corners. Review of the 1984 original design documents and detail book were used to augment the on-site observations.

Visual observations of the exterior face of the veneer identified the extent of the aforementioned pre-cast sill damage, previous repairs and subsequent further cracking to the pre-cast window headers, mortar popping out of the joints, sealant failure along masonry control joints, rust staining corresponding to the veneer ledgers, and weeps were not visible along the ledger locations. In addition, dirt, debris, and other exterior material had blocked the built-in aluminum window frame weep holes.

In review of the design documents, it was noted that not all details followed industry standards. In specific, flashing was absent from some details. Other details indicated an incomplete flashing system for adequate protection of veneer walls. No three dimensional drawings for indicating flashing termination were included.

Part 2 of the assessment involved creating openings in the wall system both on the exterior and the interior. The purpose of the invasive openings was to verify that the wall was constructed as designed, to confirm if additional flashing was installed, and to determine if water intrusion was contributing to the visible damage. Given the degree of deterioration observed on the exterior, target locations for wall openings were performed of the interior face of the gypsum board immediately adjacent to the interior aluminum window sills.

FINDINGS

The results of the invasive openings were significant in providing evidence of how lack of proper flashing can damage wall components while high internal positive air pressure can limit the damage to interior systems and protect veneer building envelope enclosure systems from extensive water intrusion.

The as‐built conditions, in some locations, varied considerably from the design details. No flashing was installed below the pre-cast window sills and no flashing was installed along the interface between the vertical window system and veneer walls. An outer layer of backer rod behind the vertical sealant joint and inner layer of backer rod behind the gypsum board were the only line of defense against water intrusion. Adequate and substantial copper flashing protected the steel ledger but all rope weeps (a common Post-Modern era construction material for veneer walls) were installed at proper spacing but did not extend to the exterior thereby trapping water against the ledger angles. Beyond the initial outer layer of defense against water intrusion (sealant system, veneer wall, and aluminum window system) there is no back up / secondary protection in place.

No interior finish systems appear to be damaged. The lack of adequate flashing does not currently create interior water intrusion. Current water intrusion is isolated to materials outward of the concrete structural frame. The lack of damage to the interior can be attributed to the high positive air pressure which in turn creates high volume of air flow within the interior air gap inward of the concrete frame. This positive pressure acts as a mitigating element against bulk water intrusion. Combined with the thickness of the concrete structural wall (approximately 12 inches), water intrusion is isolated to the masonry veneer system. Even at the aluminum window frame interface, the two layer of backer rod are sufficient to block water intrusion with a positive air pressure environment.

Recently installed new roof coping provided the means to mitigate the lack of through wall flashing along the parapet and greatly reduced water intrusion in the veneer wall air cavity. Given the age of the building, and visual observations, damage has already occurred prior to the new roof coping. In addition, the lack of flashing increases the need to routinely replace deteriorated sealant systems and maintain weeps on both the veneer wall and the aluminum window system. The extensive existing damage to the pre-cast components will require full replacement. During replacement, further assessment of structural components can be made and adequate flashing and weeps can be installed. The pre-cast replacement process may also serve as an opportunity to mock up potential secondary defense systems at the aluminum window frame/veneer wall interfaces. At this time the laboratory use requiring positive air pressure is protecting the interior. However, should the use of the building coincide with lowering of the pressure and air flow, a secondary means to prevent water intrusion will be required. For now, the large amount of air flow with in the cavity provides sufficient temperature and flow volume to adequately dry the cavity space.

Veneer systems, especially those constructed during the Post-Modern era require attention to the flashing details and corollary protective systems like sealant joints, weep holes, and preventive maintenance procedures to prolong the life of the structure and reduce the need for substantial repairs.

Written by Peter Meijer, AIA, NCARB / Principal, and PMA architectural staff.