Post Modern Architecture: Documentation and Conservation

At the DoCoMoMo US, Modern Matters, conference April 2013 in Sarasota, Florida, DoCoMoMo Oregon presented a debate on the merits of Michael Graves Portland Building and on the larger context of Post Modernism in general. A lively debate at the end of the presentation centered on the merits of DoCoMoMo incorporating Post Modern under the mission of the organization. In general, the support, or lack of support, for an expanded interpretation separated into two distinct viewpoints. The division represented the difference between individuals that look at Post Modernism as a historic event and individuals that still perceive Post Modernism as bad design even if executed within their own practice.

In a seemingly short period of time, a lot has transpired since 2013 regarding the conservation of Post Modernism. After a presentation on Post Modernism: Are You Prepared to Protect It during the Modern Heritage track at the October 2014 Association for Preservation Technology (APT) Conference in Quebec City, the APT Board unanimously supported the need to get ahead of the technical issues associated with preserving Post Modern architecture.

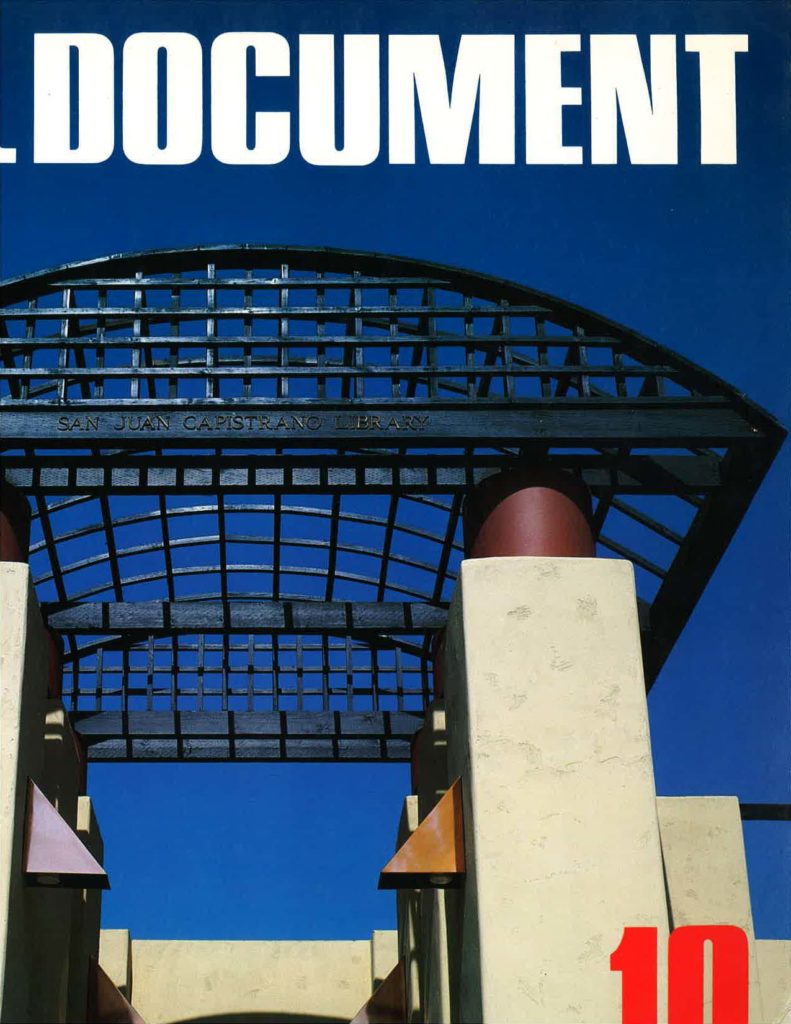

And in December 2015, the Princeton School of Architecture, educational forum for Michael Graves, hosted the Postmodern Procedures Conference. Described in the conference outline, there was a “particular emphasis on methods of documentation and analysis, technical and narrative drawing” related to Postmodern. Post Modern works, buildings, sites, and neighborhoods, as well as art works, are recognized as important design styles deserving conservation and further understanding of construction techniques. And many iconic structures are being negatively modified (Richard Meier, Bronx Development Center, 1977) or lost entirely (James Wines, Sculpture in the Environment (SITE), Best Product Stores, circa 1976). <1>

Post Modern design was broadly practiced in both the United States and internationally. Large and small firms were attracted to the stylistic incorporation of classical western design vocabulary in stark juxtaposition against the plain, unadorned, square box that many argued architecture had become. Post Modern architects, engineers, and material suppliers were pushing new materials and innovative construction technologies as a way to create Post Modern design elements. Continuous innovation in building skins reintroduced porcelain enamel panels, a product brought by Lustron to the building industry during the housing boom following World War II. New skins made from Glass Fibre Resin (GFR) capable of being molded in classical curves and ornamental shapes favored by Post Modern design were created. Innovations in brick technology including large scale brick panels made from a single wythe of masonry to panels whose outer face was only one half inch of masonry, or thin bricks. Improvements in resins created new wood or simulated wood products and adhesives for mounting faux finishes to structural systems. Perhaps one of the more ubiquitous new materials used in the creation of Post Modern architecture was the faux stucco product Dryvit, an Exterior Finish Insulation System (EIFS). Like porcelain enamel panels, EIFS was introduced as insulated wall assemblies as a means to improve energy performance during the world’s energy crisis of the 1970s.

Outside of dramatic assembly failures, particularly within the EIFS industry, that provide insight into Post Modern material and assemblies, much technological information has been relegated to the historical archives. Many Post Modern buildings incorporate systems or components that are neither produced nor currently assembled in similar manners due to improvements in technology and building envelope science. Therefore, the process and method of building restoration, rehabilitation, and/or focused envelope repair could dramatically impact the exterior character of Post Modern structures.

Focusing on one popular building skin material, Alucobond, much in use during the 1980s provides insight into the need for more research and deeper understanding of Post Modern assemblies and how to conserve and protect these systems.

Origins & Development

Alucobond falls into the category of aluminum composite panels (ACP) or sandwich panels. Alcan Composites & Alusuisse invented aluminum composites in 1964 and commercial production of Alucobond commenced in 1969, followed by Dibond in 1989.<2> ACPs are used in a variety of industries ranging from aerospace to construction. Perhaps the most well recognized structure using ACP is the Epcot Center’s Space Ship Earth built in 1982. However, it is the work of Richard Meier and I.M. Pei during the 1980s that brought Alucobond into the forefront as an architectural cladding material. Several different skin materials are available including aluminum, zinc, copper, titanium and stainless steel.

Manufacturing

The major aluminum raw ingredient, bauxite, is mined throughout the world with US sources coming from Georgia, Jamaica, and Haiti. Processing of the bauxite predominantly occurs near the ocean ports, like Corpus Christi, where the raw material is off loaded. Manufacturing starts from either solid blocks of aluminum made into coil sheets or directly from pre-manufactured coil sheets. Assembly occurs along a continuous operating line that bonds the weather (exterior) and interior faces to the core, cuts the panel to length, and produces special shapes as needed.

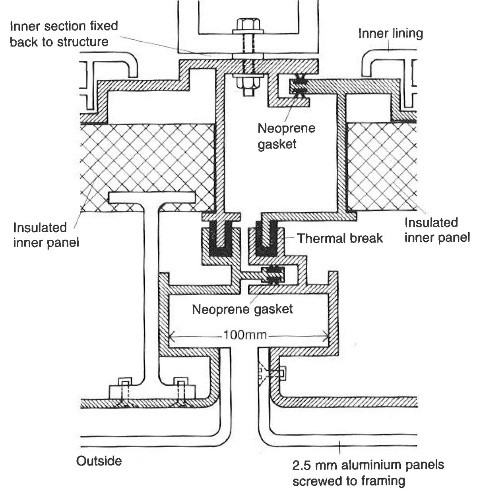

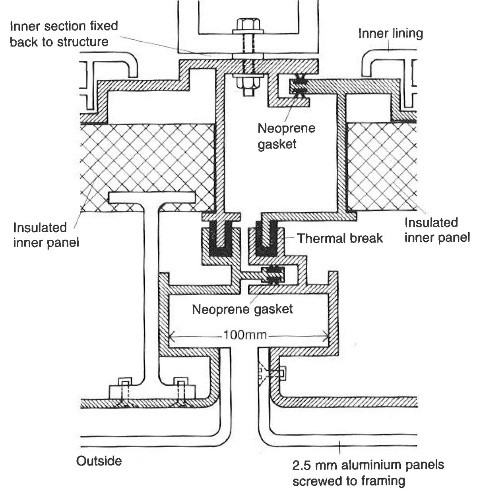

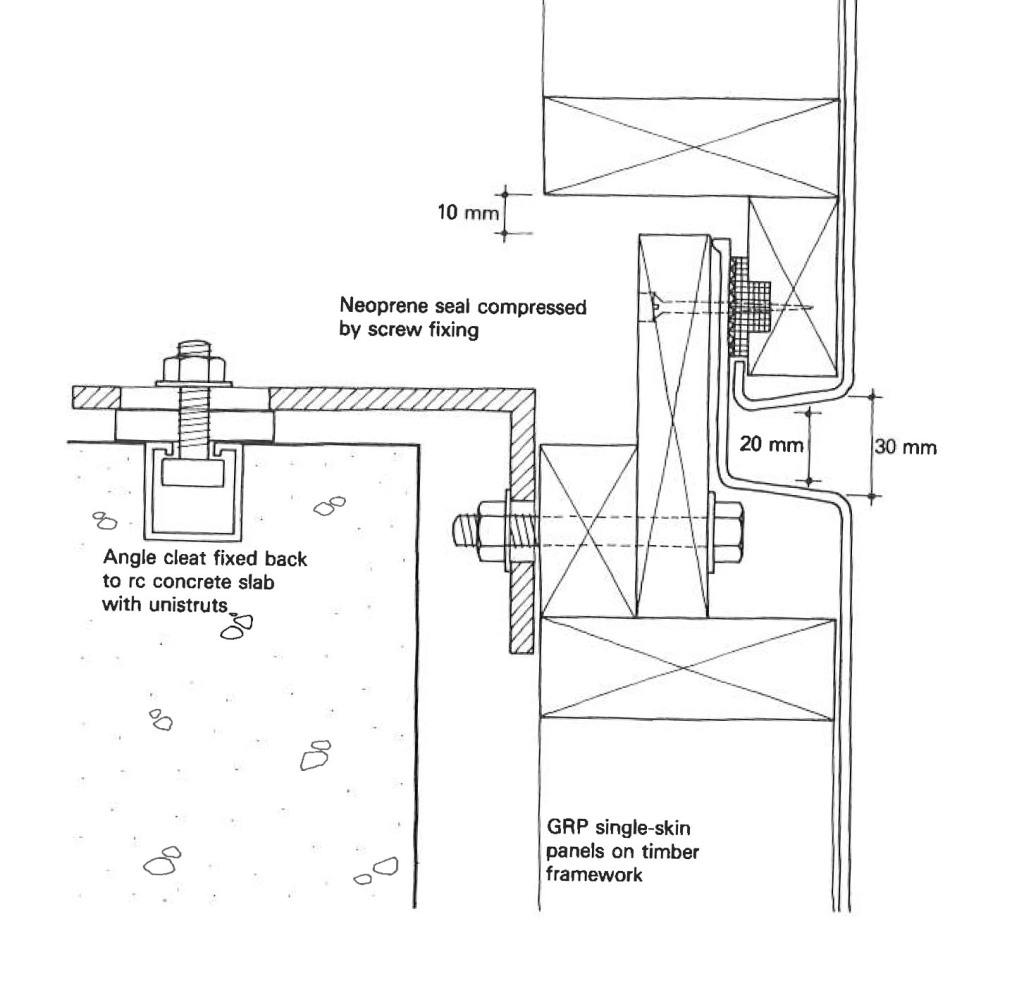

Aluminum Composite Panels (ACP) are high-performance wall cladding products typically consisting of two sheets of nominal 0.020″ (0.50 mm) aluminum permanently bonded to an extruded thermoplastic core (polyethylene). Assemblies in the mid-1980s would often consist of curtain wall sub-components with sheets of aluminum on the exterior and insulation placed behind the aluminum sheets. (See fig)

ACP can be roll formed to curve configurations for column covers, architectural bullnoses, radius-building corners and other applications requiring radius forming. This process can be accomplished with a “pyramid” roll forming machine, which consists of three motor-driven adjustable rollers. You can successfully roll form ACP using machines with minimum 2 1/2″ (64 mm) diameter rolls. The operator normally makes multiple passes of the panel through the rollers to gradually obtain the desired radius. <3>

Use & Methods of Installation

Post Modern assemblies generally assumed water would get behind the face aluminum panel and need a weep path to exit the system. Air gaps were incorporated to induce drying and allow for weeping via gravity. Wind loads were accommodated through additional brackets, or stiffeners, set behind the face panel and connected to sub-framing. Much of the technology was based on curtain wall knowledge.

The panel systems could often be complex in the attachment to the structure, but the face panels were very similar to panels of today.

Conservation

Deterioration mechanism are generally associated with the system assembly and rarely are there failures in individual panels beyond cosmetic damages to the face aluminum including fading colors, scratches, and impact damages. More often incorrect fasteners were used that create galvanic reaction between the fastener and aluminum panel or inadequate fasteners were used to accommodate structural loads. The lack of design for thermal movement between panels, over the height and length of the panel façade, or along edge interfaces with sealants are also key areas of assembly failures.

Fortunately manufactures of Alucobond, or other aluminum composite panels, are still manufacturing the panel and components making in-kind replacement a viable conservation option. Inadequate structural systems can be reinforced through disassembly of the ACP for access to the structural support. Laser scanning technology has greatly enhanced the accuracy of recording existing conditions and is critical in reproducing replacement panels. Although labor intensive, most of the systems were attached using stainless steel fasteners. Like modern curtain walls, sealant and gaskets will be removed during disassembly and require reinstallation.

Repainting or repairing surface defects is feasible but the results generally do not achieve the same quality of finish as the factory applied coating process. And as with all repainting projects, surface preparation is critical to the long-term success of the project.

Loss of original Post Modern aluminum composite panel systems can be reduced through an increasing interest and research into the original design intent and assembly techniques. ACP were incorporated into Post modern structures because of the simplicity to create the curved forms and for rapid pace of construction. The systems are an important part of understanding Post Modernism and worthy of Conservation.

Marquette Plaza (historic photograph)

Written by Peter Meijer, AIA, NCARB, Principal

Space programming respected the historic floor plan and scale of the original structure and recreated Yeon’s original design intent of integrating indoor space with outdoor space. Extraneous equipment and unsympathetic additions were removed from both the interior and exterior. Interior design elements, furniture, and fixtures maintain the open gallery spacial quality while integrating new furniture and fixtures meeting the needs of the tenant. Major preservation focused on the exterior restoring original paint colors through serration studies, restoring building signage in original type style and design, preserving original wood windows, when present, and restoring the intimate courtyard with a restored operating water feature.

Space programming respected the historic floor plan and scale of the original structure and recreated Yeon’s original design intent of integrating indoor space with outdoor space. Extraneous equipment and unsympathetic additions were removed from both the interior and exterior. Interior design elements, furniture, and fixtures maintain the open gallery spacial quality while integrating new furniture and fixtures meeting the needs of the tenant. Major preservation focused on the exterior restoring original paint colors through serration studies, restoring building signage in original type style and design, preserving original wood windows, when present, and restoring the intimate courtyard with a restored operating water feature. The restoration approach is intended to correct the structural deficiencies and replace the failed members with no changes to the historic appearance of the structure. The crib design allows for insertion of new steel elements, invisible from the exterior, capable of providing additional support for vertical loads. The difficulty arises because standard wood products available today have different visible and strength attributes from standard components available in 1965. Sourcing appropriate lumber is dependent upon clear and quantifiable specification, high quality inspection, and visual qualities. There are no structural standards for reclaimed or recycled lumber compounding the incorporation of “old growth” lumber as part of a new structural system. When original source material is no longer available, best practices for narrowing the selection of new materials will of necessity be combined with subjective visual qualities and a best-guess scenario as to how the new material will age in place similarly to the historic material. There are no single solutions so experience is key.

The restoration approach is intended to correct the structural deficiencies and replace the failed members with no changes to the historic appearance of the structure. The crib design allows for insertion of new steel elements, invisible from the exterior, capable of providing additional support for vertical loads. The difficulty arises because standard wood products available today have different visible and strength attributes from standard components available in 1965. Sourcing appropriate lumber is dependent upon clear and quantifiable specification, high quality inspection, and visual qualities. There are no structural standards for reclaimed or recycled lumber compounding the incorporation of “old growth” lumber as part of a new structural system. When original source material is no longer available, best practices for narrowing the selection of new materials will of necessity be combined with subjective visual qualities and a best-guess scenario as to how the new material will age in place similarly to the historic material. There are no single solutions so experience is key. Case Study 3

Case Study 3

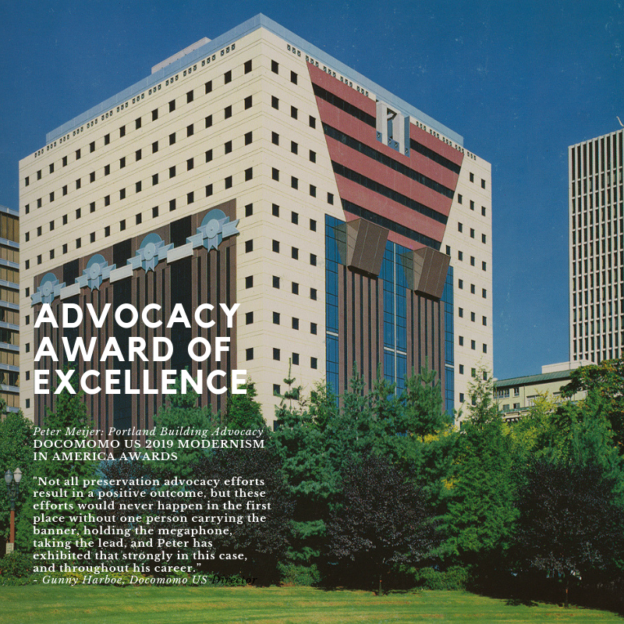

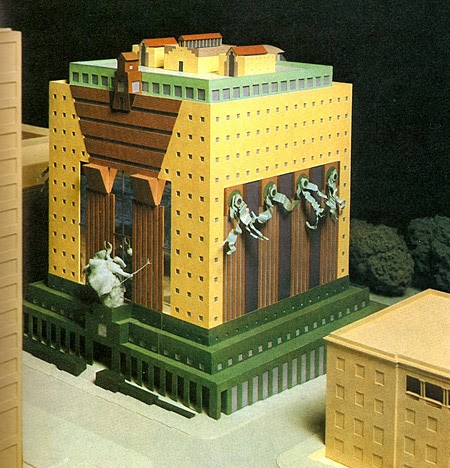

The Portland Building itself is significant as one of a handful of high-profile building designs that defined the aesthetic of Post Modern Classicism in the United States between the mid-1960s and the 1980s. Constructed in 1982, the Portland Public Service Building is nationally significant as the notable work that crystallized Michael Graves’s reputation as a master architect and as an early and seminal work of Post-Modern Classicism, an American style that Graves himself defined through his work. The structure is ground-breaking for its rejection of “universal” Modernist principles in favor of bold and symbolic color, well-defined volumes, and stylized- and reinterpreted-classical elements such as pilasters, garlands, and keystones.

The Portland Building itself is significant as one of a handful of high-profile building designs that defined the aesthetic of Post Modern Classicism in the United States between the mid-1960s and the 1980s. Constructed in 1982, the Portland Public Service Building is nationally significant as the notable work that crystallized Michael Graves’s reputation as a master architect and as an early and seminal work of Post-Modern Classicism, an American style that Graves himself defined through his work. The structure is ground-breaking for its rejection of “universal” Modernist principles in favor of bold and symbolic color, well-defined volumes, and stylized- and reinterpreted-classical elements such as pilasters, garlands, and keystones.  As one of the earliest large-scale Post-Modern buildings constructed, Graves’s design for the Portland Building was daring; almost shocking, in its vision for the future, and for its proposition as to what “after Modernism” could mean for architecture. The building itself is a fifteen-story regularly-fenestrated symmetrical monumental block clad in scored off-white colored stucco and set on a stepped two-story pedestal of blue-green tile. The building’s style is expressed through paint and applied ornament that implies classical architectural details, including terracotta tile pilasters and keystone, mirrored glass, and flattened and stylized garlands, among other elements that are intended to convey multiple meanings. For instance, the building is organized in a classical three-part division, bottom, middle, and top in reference to the human body, foot, middle, and head. At the same time, the building’s colors represent parts of the environment, with blue-green tile at the base symbolizing the earth and the light blue at the upper-most story representing the sky. The building uses layers of references to physically and symbolically tie it to place, its use, and the Western architectural tradition.

As one of the earliest large-scale Post-Modern buildings constructed, Graves’s design for the Portland Building was daring; almost shocking, in its vision for the future, and for its proposition as to what “after Modernism” could mean for architecture. The building itself is a fifteen-story regularly-fenestrated symmetrical monumental block clad in scored off-white colored stucco and set on a stepped two-story pedestal of blue-green tile. The building’s style is expressed through paint and applied ornament that implies classical architectural details, including terracotta tile pilasters and keystone, mirrored glass, and flattened and stylized garlands, among other elements that are intended to convey multiple meanings. For instance, the building is organized in a classical three-part division, bottom, middle, and top in reference to the human body, foot, middle, and head. At the same time, the building’s colors represent parts of the environment, with blue-green tile at the base symbolizing the earth and the light blue at the upper-most story representing the sky. The building uses layers of references to physically and symbolically tie it to place, its use, and the Western architectural tradition. The boxy, fifteen-story building is located in the center of downtown Portland, Oregon, occupying a full 200 by 200-foot city block right next to City Hall. The Portland Building is a surprising jolt of color within the more restrained environment and designs of nearby buildings, with its blue tile base and off-white stucco exterior accented with mirrored glass, earth-toned terracotta tile, and sky-blue penthouse. The figure of Lady Commerce from the city seal, reinterpreted by sculptor Ray Kaskey to represent a broader cultural tradition and renamed ‘Portlandia,’ is placed in front of one of the large windows as a further reference to the city. The building is notable for its regular geometry and fenestration as well as the architect’s use of over-scaled and highly-stylized classical decorative features on the building’s facades, including a copper statue mounted above the entry, garlands on the north and south facades, and the giant pilasters and keystone elements on the east and west facades. Whether or not one judges the building to be beautiful or even to have fulfilled Graves’s ideas about being humanist in nature, it is undeniably important in the history of American architecture. The building has been dispassionately evaluated in various scholarly works about the history of architecture and is inextricably linked to the rise of the Post-Modern movement.

The boxy, fifteen-story building is located in the center of downtown Portland, Oregon, occupying a full 200 by 200-foot city block right next to City Hall. The Portland Building is a surprising jolt of color within the more restrained environment and designs of nearby buildings, with its blue tile base and off-white stucco exterior accented with mirrored glass, earth-toned terracotta tile, and sky-blue penthouse. The figure of Lady Commerce from the city seal, reinterpreted by sculptor Ray Kaskey to represent a broader cultural tradition and renamed ‘Portlandia,’ is placed in front of one of the large windows as a further reference to the city. The building is notable for its regular geometry and fenestration as well as the architect’s use of over-scaled and highly-stylized classical decorative features on the building’s facades, including a copper statue mounted above the entry, garlands on the north and south facades, and the giant pilasters and keystone elements on the east and west facades. Whether or not one judges the building to be beautiful or even to have fulfilled Graves’s ideas about being humanist in nature, it is undeniably important in the history of American architecture. The building has been dispassionately evaluated in various scholarly works about the history of architecture and is inextricably linked to the rise of the Post-Modern movement.