On a recent trip to Italy, I couldn’t help but contemplate the progression of architecture styles across time and contemporary architecture’s divergence/evolution from past practice. Architecture, alongside art, has long reflected contemporary trends, culture, and politics. More than ever, contemporary architecture reflects our societies’ obsession with technology, efficiency, and value-engineering. As I stood within the walls of Carlos Scarpa’s Brion Cemetery, taking in the attention to detail and crafted experience of the space, I wondered if architecture would ever return to this level of craft, detail, and whimsy. It is hard to image Carlos Scarpa’s intricate and unique detail being created in the architectural world today. From my perception, the art of architecture on a mass scale is being transformed to a systems and science of architecture where unique, non-functioning, artful details are being abandoned as superfluous and cost prohibited.

A Paradigm Shift

Great works of historic architecture were conceived by pen and paper as artistic minds envisioned each space on iterative gestural pages; translated from enigmas to sketches to drawings to reality. Materials were crafted by hand and details seamlessly integrated within each trade’s identity. Today’s paradigm shift toward Building Information Modeling (BIM), factory production, and intelligent building systems have transformed the means and methods of the tradition discipline. Traditional detailing known by each trade has been lost to time as architects and builders move to new systems. The design process has continued to evolve and transitioned to computer based iterative processes. This creates a new dialog where the computer program itself has an influence over the design.

Architectural contemporary styles are named for the processes in which they were designed, such as Diagramism, Revitism, Scriptism, and Subdivisionism. These processes include designing in CAD, BIM, and other 3D programs, which can predominantly drive the design style and form. Architects and designers need to be aware of how architectural design is affected by each program’s restrictions and work flow tendencies. There can be a detachment for the final goal of the built form as we go down the virtual rabbit hole. The benefit of 3D modeling is that it allows designers to more fully comprehend form and its intersection with the overall building systems. However, if the design process is pushed into modeling without a strong concept, the objective can be easily replaced with creating a well-organized and systematic Building Information Modeling, instead of holistic architectural design.

Architectural Design and BIM

BIM designs are based primarily of component systems that create efficient, intelligent, and informative models. Designers can easily draw schedules and quantities that greatly speed up processes, however in the design process, focusing on components can also create a disassociation from the whole building and design concept. The translation of an artistic gesture of a material or space can easily be lost in the clunky world of 3D representation and restrictions.

I am certainly a proponent of BIM, but I am also an advocate of preserving the art and craft of architecture. BIM is a terrific for understanding buildings in their 3D form as a composition of components and systems. BIM’s intelligence allows for continued updating of schedules and quantities, allowing for time efficiency. However, these components are limited to the software’s modeling options and the designer’s skill at modeling. The virtual world is still not an accurate representation of all the properties of building materials or their structural capabilities. In other words, BIM cannot be a means from the start to the end. Our profession is obligated to continue to push for high design standards and syndicate and extrapolate. I continue to see architecture that either allows BIM to drive design or prioritizes efficiency and value-engineering over quality of design. As BIM evolves within architecture as a means to design, I hope it can assist designers in their creative process and challenge our profession’s boundaries.

Written by Hali Knight, Architect I

Sources

Prospect Magazine

Archdaily

DI

Buildings constructed before 1965 have reached the age of eligibility for being considered historic by the standards of the National Register. That means that much of Modern Architecture, the general period ranging from 1950 through 1970, is historic, or soon will be considered historic as the 50-year mark is crossed. As historians assess and study Modern Architecture, we provide ever more precise descriptions and terms to describe the sub-styles and variations within the large umbrella term, “Modern.” As in taxonomy, which classifies and categorizes living organisms, we can recognize and assign groups of similar resources together for study.

Buildings constructed before 1965 have reached the age of eligibility for being considered historic by the standards of the National Register. That means that much of Modern Architecture, the general period ranging from 1950 through 1970, is historic, or soon will be considered historic as the 50-year mark is crossed. As historians assess and study Modern Architecture, we provide ever more precise descriptions and terms to describe the sub-styles and variations within the large umbrella term, “Modern.” As in taxonomy, which classifies and categorizes living organisms, we can recognize and assign groups of similar resources together for study.

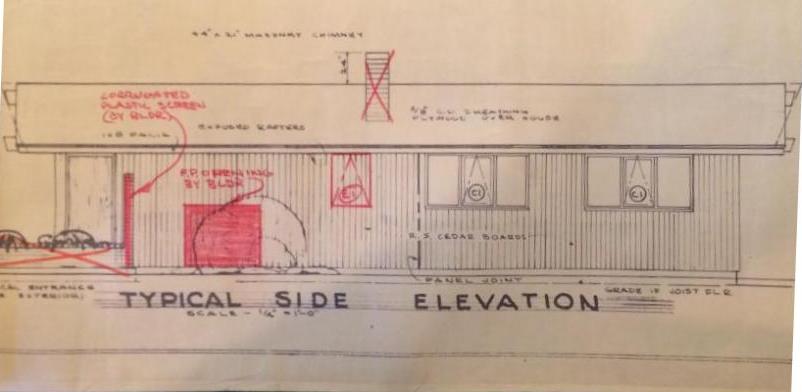

The Olympia survey classified the first grouping of styles as those that are transitional. Transitional Modern styles have some elements of Modern and some elements of more traditional architecture. Windows might be vertically-oriented, double-hung wood windows (traditional) rather than having horizontal proportions (Modern). A roof might be a moderate pitch, with minimal overhangs (traditional), rather than a shallow pitch with outwardly-extending gables (Modern). In Olympia, 37% of the houses surveyed were Modern Minimal Traditional, by far the most prevalent Transitional Modern style.

The Olympia survey classified the first grouping of styles as those that are transitional. Transitional Modern styles have some elements of Modern and some elements of more traditional architecture. Windows might be vertically-oriented, double-hung wood windows (traditional) rather than having horizontal proportions (Modern). A roof might be a moderate pitch, with minimal overhangs (traditional), rather than a shallow pitch with outwardly-extending gables (Modern). In Olympia, 37% of the houses surveyed were Modern Minimal Traditional, by far the most prevalent Transitional Modern style.  Ranch style architecture is the style that architecture critics have generally spurned, since houses were often constructed by contractors without architect’s involvement. Ranch buildings are broad, one-story, and horizontal in overall proportion. They have an attached garage which faces the street and is part of the overall form of the house, and almost always a large picture window facing the street as well. Cladding is used to accentuate the horizontal lines of the house, so there is often a change in material at the lower part of the front façade- brick veneer was a popular choice. Many of the sub-styles of Ranch architecture are “styled” Ranch houses, meaning that elements from another style of architecture were placed on a Ranch form building. One example is Storybook Ranch, which uses “gingerbread” trim, dormers or a cross-gable, and sometimes diamond-pane windows. Are these decorated sub-styles still part of the canon of Modern Architecture? In many ways, they are more Post-Modern than Modern, but that distinction is worthy of an involved discussion of its own.

Ranch style architecture is the style that architecture critics have generally spurned, since houses were often constructed by contractors without architect’s involvement. Ranch buildings are broad, one-story, and horizontal in overall proportion. They have an attached garage which faces the street and is part of the overall form of the house, and almost always a large picture window facing the street as well. Cladding is used to accentuate the horizontal lines of the house, so there is often a change in material at the lower part of the front façade- brick veneer was a popular choice. Many of the sub-styles of Ranch architecture are “styled” Ranch houses, meaning that elements from another style of architecture were placed on a Ranch form building. One example is Storybook Ranch, which uses “gingerbread” trim, dormers or a cross-gable, and sometimes diamond-pane windows. Are these decorated sub-styles still part of the canon of Modern Architecture? In many ways, they are more Post-Modern than Modern, but that distinction is worthy of an involved discussion of its own.  The Olympia Mid-Century Residential survey found over half the resources surveyed to be Ranch or variants of Ranch style. 31% of the surveyed homes were identified as simply Ranch, with another 11% Early Ranch, 9% Contemporary Ranch, 4% Split-Level or Split-Entry, and 4% one of the “Styled” Ranch variations. Sheer numbers alone remind us that the Ranch is deserving of study and shows us how the majority of middle-class Americans lived. As Alan Hess writes in his book Ranch House,

The Olympia Mid-Century Residential survey found over half the resources surveyed to be Ranch or variants of Ranch style. 31% of the surveyed homes were identified as simply Ranch, with another 11% Early Ranch, 9% Contemporary Ranch, 4% Split-Level or Split-Entry, and 4% one of the “Styled” Ranch variations. Sheer numbers alone remind us that the Ranch is deserving of study and shows us how the majority of middle-class Americans lived. As Alan Hess writes in his book Ranch House,