Schools come in all shapes and sizes. They are one-story and two-story. Schools serve young children, teenagers, and adults alike, and they are designed in all manner of style. In most instances, schools appear to be historic because of these architectural features. However, there is another yard stick with which to measure school building’s role in architectural history. As with all things, time changes our understanding and perspective, and educational theory is no different. Each school building reflects modern thought and beliefs of the era.

When imagining a school that is two-stories, designed in a classical, Spanish, or other revival style with a central corridor flanked by classrooms, it is likely to be a school from the Progressive era of education. The Progressive Era spans from the end of the nineteenth century to World War II. During this period, there was a shift from informal education to an organized system structed by putting age groups into grade levels and creating a curriculum based on intellectual rigor and mental discipline.

EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY SCHOOL DESIGN

By the early twentieth century, school buildings were becoming more specialized and standardized as educators pushed for more control of school design. Plan books and design guides for educational buildings were introduced. There was a movement to make schools a healthier environment, improving ventilation and illumination. H-plan schools were introduced to bring more light and air into classrooms. Early twentieth-century school buildings typically featured traditional architectural styles, monumental designs, symmetrical facades, oversized entrances, and rectangular plans. Designed as civic monuments, the architectural focus was on building a school that would be a source of community pride. [1]

However, despite various applied stylistic details on the exteriors, the interiors were generally the same. The classroom was the basic building block for the school building, stacked vertically and horizontally to form a school. Classrooms were identical and all featured fixed desks facing the teacher at the front of the room with windows along one wall providing a single-direction light source. The emphasis was on order and authority. [2]

In 1918, the federal Office of Education published Cardinal Principles of Secondary Education. It established a list of seven key elements that education should encompass: command of basic skills, health, family values, vocation, civic education, worthy use of leisure time, and ethical character. Clearly influenced by Progressive ideals, the publication emphasized personal development rather than academic criteria. [3] It developed seven tenets of Progressive education: freedom to develop naturally; interest in the motive of all work; the teacher as a guide, rather than task-master; scientific study of pupil development; greater attention to conditions that affect a child’s physical development; co-operation between school and home to meet the needs of child-life; and the Progressive as a leader in educational movements. Progressive educational ideals were being widely implemented in schools by the 1930s. [4]

There was a considerable lack of new schools constructed between 1930 and 1945, due to a lack of funding during the Great Depression and lack of available building materials during World War II. Educators at the 1947 National Conference for the Improvement of Teaching recommended a ten-billion-dollar building program over the next decade to meet the classroom demand, estimating that “between 50 and 75 percent of all school buildings were obsolete and should be replaced immediately.” [5] At the time, general consensus among educators was that the lifespan of a school was 25 to 50 years after which new teaching methods and technology made it obsolete. Moreover, the population of the United States was increasing at a faster rate than schools could keep up with and soon overcrowded schools became commonplace. New schools were desperately needed, and like the previous Progressive era schools reflected education theory of the day, so too did mid-century schools.

MID-CENTURY SCHOOL DESIGN AND PLANNING

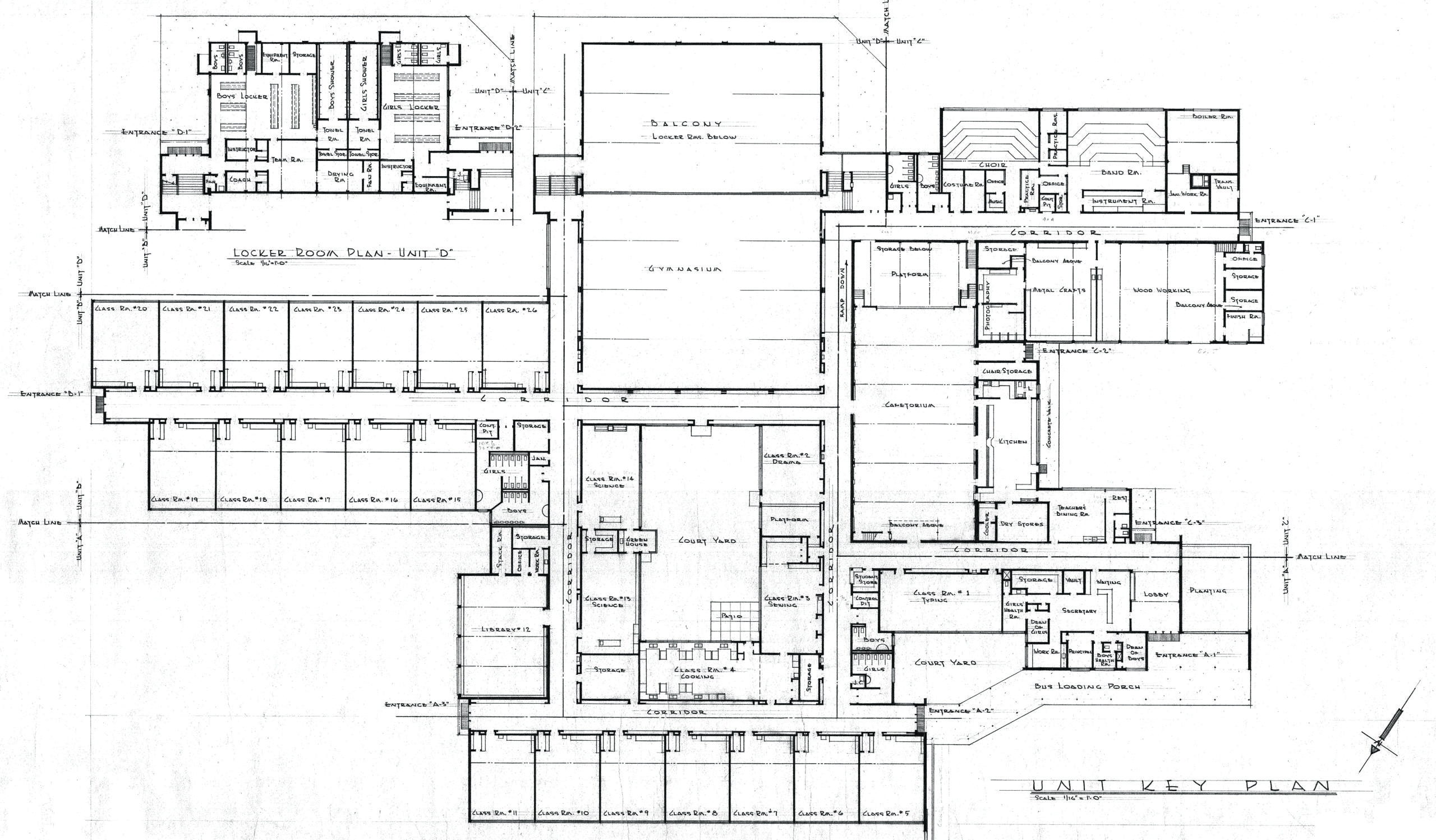

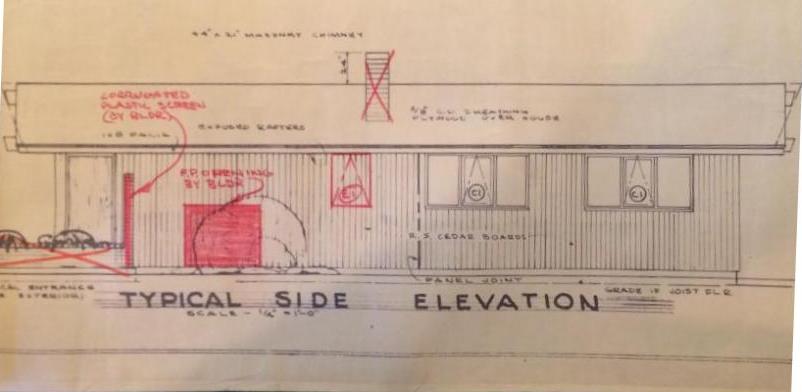

After World War II, schools stopped serving just the physical and educational needs of students but took interest in nurturing students’ emotional development. Schools of this era were typically long and low, one-story buildings designed in the International style with enormous windows, light-filled courtyards, and a decentralized floorplan.

According to mid-century educators, successful school planning required balancing three primary concerns: environment, education, and economy. The district needed to provide the best possible environment for students and teachers in order to facilitate learning while working within the limitations of the budget. [6] New schools had to meet both physical needs – sanitary, safe, quiet, well-lit – and emotional needs – pleasant, secure, inspiring, friendly, restful. In the Northwest, most schools reflected regional style by incorporating an interior courtyard. [7] During this period, the progressive theory of education was common. This theory was based on the concept that education should include the general welfare of students, not just their intellectual development, and that students should aspire to individuality not conformity. Teachers were encouraged to have a democratic classroom where they worked collaboratively with students rather than lecturing, and assignments were active and engaging rather than reading and watching. Additional topics were added to the curriculum that would better prepare students for the next phases in their lives, these topics included woodshop, home economics, and physical education. The general welfare of students was better minded and encompassed hot lunches, health services, and changes to disciplinary actions. [8]

The other hurdle for school districts was the rising cost of construction in the post-War era. For example, in 1930, $100,000 would buy a ten-room school, in 1940, it would buy an eight-room school and in 1950, it would buy a four-room school. [9] Fortunately for school district budgets, many communities wanted modern design schools rather than the neo-classical or art deco designs from previous decades, and these modern designs were less expensive to build. Mid-century schools and houses utilized new technologies, materials, and mass production methods to meet the demand for affordable and fast construction. [10] Classrooms also featured extensive built-ins that included sinks, slots for bulky roles of paper, and coat storage.

TYPICAL MID-CENTURY DESIGN ELEMENTS

Mid-century schools and suburban housing shared many design elements, including: floorplans laid out to maximize space and flexibility; floorplans, fenestration, and landscaping designed to create connections between indoor and outdoor spaces; facades featuring large windows and ribbon windows; buildings designed to accommodate easy expansion later; decorative elements replaced with contrasting wall materials on the exterior; floorplans encouraged socializing; single-story designs with flay or low pitch roofs and deep eave overhangs; and buildings integrated into the landscape. Mid-century schools featured larger sites and a greater emphasis on landscaping and outdoor recreation. This resulted in more sprawling school designs. Instead of compactly containing all school facilities within a single rectangular block, facilities were clustered by function, such as separating quiet classrooms from noisy cafeterias. Plans were often irregular.

Schools are designed from the inside out and what is on the inside reflects education theory and beliefs of the day. The next time you admire a school’s architecture, be sure to notice more than its visual aesthetic, but its role in the pursuit of education.

Written by Tricia Forsi, Preservation Planner.

Sources

[1] Donovan, John J. School Architecture: Principles and Practices. New York: MacMillan Company, p. 24

[2] Weisser, Amy S. “’Little Red School House, What Now?’ Two Centuries of American Public School Architecture.” Journal of Planning History. Vol. 5, No. 3. August 2006, p. 200

[3] Graham, Patricia Albjerg. Schooling America: How the Public Schools Meet the Nation’s Changing Needs. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 76-77

[4] Weisser 2006, 203

[5] Benjamin Fine, “Broader Vocational System Is Advocated to Help Meet Modern Industrial Needs,” New York Times, April 11, 1948.

[6] William W. Caudill, Toward Better School Design, New York: F. W. Dodge Corporation, 1954,

[7] Entrix, Inc., Portland Public Schools Historic Building Assessment, October 2009, p. 3-18

[8] “Modern Design Transforms Schools.” New York Times. August 24, 1952; “Modern Schools Are Built to Fit Child Emotionally and Physically,” New York Times, December 23, 1956; New Schools of Thought: Modern Trend in Education Is Reflected in Buildings Themselves,” New York Times, December 16, 1952; Abigail Christman, National Register of Historic Places Nomination: Colorado’s Mid-Century Schools, 1945-1970,” May 1, 2017

[9] “New Schools, U.S. Is Building Some Fine Ones But Is Facing A Serious Shortage.” Time. October 16, 1950, p. 80

[10] Otaga, “Building for Learning in Postwar American Elementary Schools.” p. 563.

Since its creation in 1862, the ballpark has continued to have an influential impact on those who experience it. This impact is not only measured by heritage tourism to these sites, like Fenway Park or Wrigley Field, but also by how they are preserved. In some cases, such as Fenway Park, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, ballparks are preserved in a very traditional sense of the word. However, most ballparks never have the opportunity to reach the benchmarks needed to be preserved according to these preservation standards and are therefore preserved through a variety of alternative preservation methods. These methods, which span the spectrum from preserving a ballpark through the presentation of their original objects in a museum to the preservation of existing relics in their original location, such as Tiger Stadium’s center field flag pole, have given a large segment of our society an opportunity to continue their emotional discourse with this architectural form. Yet, the results of these preservation methods are commonly only the conclusion to a greater act of ceremony and community involvement that preludes them.

Since its creation in 1862, the ballpark has continued to have an influential impact on those who experience it. This impact is not only measured by heritage tourism to these sites, like Fenway Park or Wrigley Field, but also by how they are preserved. In some cases, such as Fenway Park, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, ballparks are preserved in a very traditional sense of the word. However, most ballparks never have the opportunity to reach the benchmarks needed to be preserved according to these preservation standards and are therefore preserved through a variety of alternative preservation methods. These methods, which span the spectrum from preserving a ballpark through the presentation of their original objects in a museum to the preservation of existing relics in their original location, such as Tiger Stadium’s center field flag pole, have given a large segment of our society an opportunity to continue their emotional discourse with this architectural form. Yet, the results of these preservation methods are commonly only the conclusion to a greater act of ceremony and community involvement that preludes them.  Part of this ceremony and community involvement is the simple act of participating in the ritual that is the game itself. Most often this is conducted through observation, as society, architecture, and sport become one for nine innings. However, other documented examples of ceremony and community involvement that express the level of compassion our society has for ballparks include ritualistic acts, such as the digging up and transferring of home plate. In some cases, this ritual has included the transferring of home plate via helicopter, limousines, or police escort. Ceremonies like this have also included, for better or worse, the salvaging of dirt, sod, and other relics from a ballpark to be, either cherished as a memento or repurposed in new stadiums. Nevertheless, these examples of ceremony only scratch the surface of the depth that is our society’s infatuation with sport and its architecture, more specifically the ballpark.

Part of this ceremony and community involvement is the simple act of participating in the ritual that is the game itself. Most often this is conducted through observation, as society, architecture, and sport become one for nine innings. However, other documented examples of ceremony and community involvement that express the level of compassion our society has for ballparks include ritualistic acts, such as the digging up and transferring of home plate. In some cases, this ritual has included the transferring of home plate via helicopter, limousines, or police escort. Ceremonies like this have also included, for better or worse, the salvaging of dirt, sod, and other relics from a ballpark to be, either cherished as a memento or repurposed in new stadiums. Nevertheless, these examples of ceremony only scratch the surface of the depth that is our society’s infatuation with sport and its architecture, more specifically the ballpark.  Ceremonial Acts & Community Involvement Efforts

Ceremonial Acts & Community Involvement Efforts  Led by the Friends of Civic Stadium president, Dennis Hebert, the organization held a wake in honor of their lost historic building. The wake, intimate in size, resembled a jazz funeral with a procession to the remains of the ballpark led by the One More Time Marching Band. Once at the site of the ballpark, there were multiple ritualistic acts that mimicked traditional funeral ceremonies. These acts included a moment of silence, a passionate speech by Dennis Hebert, and the always haunting rendition of Amazing Grace on bagpipes. After the ceremony, the Friends of Civic Stadium and the friends of Friends of Civic Stadium proceeded back to Tsunami Books where they continued to express their condolences and fond memories of the lost historic ballpark.

Led by the Friends of Civic Stadium president, Dennis Hebert, the organization held a wake in honor of their lost historic building. The wake, intimate in size, resembled a jazz funeral with a procession to the remains of the ballpark led by the One More Time Marching Band. Once at the site of the ballpark, there were multiple ritualistic acts that mimicked traditional funeral ceremonies. These acts included a moment of silence, a passionate speech by Dennis Hebert, and the always haunting rendition of Amazing Grace on bagpipes. After the ceremony, the Friends of Civic Stadium and the friends of Friends of Civic Stadium proceeded back to Tsunami Books where they continued to express their condolences and fond memories of the lost historic ballpark.

Greatly influenced by the 1936 publication of John Yeon’s Watzek House, Oregon architects began to experiment with wood skins and “Mt. Hood” entry facades reminiscent of Yeon’s design. The idea that wood was symbolic of Northwest character continued through the 1950s and 1960s mid-century modern aesthetics. Local architects like Francis Jacobberger, McCoy & Bradbury, Pietro Belluschi, and others crafter their designs from outside to inside using local species of wood while simultaneously using wood to express the structural elements.

Greatly influenced by the 1936 publication of John Yeon’s Watzek House, Oregon architects began to experiment with wood skins and “Mt. Hood” entry facades reminiscent of Yeon’s design. The idea that wood was symbolic of Northwest character continued through the 1950s and 1960s mid-century modern aesthetics. Local architects like Francis Jacobberger, McCoy & Bradbury, Pietro Belluschi, and others crafter their designs from outside to inside using local species of wood while simultaneously using wood to express the structural elements.

Well known Oregon artists, including Ray Grimm, a ceramists, created the dominating Tree of Life mosaic on the west façade. LeRoy Setziol, the “Father of Wood Carving in Oregon,” created the wood Stations of the Cross and baptismal font. Surprisingly Setziol was commissioned to execute the stained glass windows as well. And Lee Kelly, one of Portland’s best known metal sculptors, enriched the church with delicate displays of metal work both on the interior and exterior. Queen of Peace is a marvelous collaboration of architecture, art, and technical daring creating a wonderful display of Oregon indigenous mid-century religious architecture.

Well known Oregon artists, including Ray Grimm, a ceramists, created the dominating Tree of Life mosaic on the west façade. LeRoy Setziol, the “Father of Wood Carving in Oregon,” created the wood Stations of the Cross and baptismal font. Surprisingly Setziol was commissioned to execute the stained glass windows as well. And Lee Kelly, one of Portland’s best known metal sculptors, enriched the church with delicate displays of metal work both on the interior and exterior. Queen of Peace is a marvelous collaboration of architecture, art, and technical daring creating a wonderful display of Oregon indigenous mid-century religious architecture. Buildings constructed before 1965 have reached the age of eligibility for being considered historic by the standards of the National Register. That means that much of Modern Architecture, the general period ranging from 1950 through 1970, is historic, or soon will be considered historic as the 50-year mark is crossed. As historians assess and study Modern Architecture, we provide ever more precise descriptions and terms to describe the sub-styles and variations within the large umbrella term, “Modern.” As in taxonomy, which classifies and categorizes living organisms, we can recognize and assign groups of similar resources together for study.

Buildings constructed before 1965 have reached the age of eligibility for being considered historic by the standards of the National Register. That means that much of Modern Architecture, the general period ranging from 1950 through 1970, is historic, or soon will be considered historic as the 50-year mark is crossed. As historians assess and study Modern Architecture, we provide ever more precise descriptions and terms to describe the sub-styles and variations within the large umbrella term, “Modern.” As in taxonomy, which classifies and categorizes living organisms, we can recognize and assign groups of similar resources together for study.

The Olympia survey classified the first grouping of styles as those that are transitional. Transitional Modern styles have some elements of Modern and some elements of more traditional architecture. Windows might be vertically-oriented, double-hung wood windows (traditional) rather than having horizontal proportions (Modern). A roof might be a moderate pitch, with minimal overhangs (traditional), rather than a shallow pitch with outwardly-extending gables (Modern). In Olympia, 37% of the houses surveyed were Modern Minimal Traditional, by far the most prevalent Transitional Modern style.

The Olympia survey classified the first grouping of styles as those that are transitional. Transitional Modern styles have some elements of Modern and some elements of more traditional architecture. Windows might be vertically-oriented, double-hung wood windows (traditional) rather than having horizontal proportions (Modern). A roof might be a moderate pitch, with minimal overhangs (traditional), rather than a shallow pitch with outwardly-extending gables (Modern). In Olympia, 37% of the houses surveyed were Modern Minimal Traditional, by far the most prevalent Transitional Modern style.  Ranch style architecture is the style that architecture critics have generally spurned, since houses were often constructed by contractors without architect’s involvement. Ranch buildings are broad, one-story, and horizontal in overall proportion. They have an attached garage which faces the street and is part of the overall form of the house, and almost always a large picture window facing the street as well. Cladding is used to accentuate the horizontal lines of the house, so there is often a change in material at the lower part of the front façade- brick veneer was a popular choice. Many of the sub-styles of Ranch architecture are “styled” Ranch houses, meaning that elements from another style of architecture were placed on a Ranch form building. One example is Storybook Ranch, which uses “gingerbread” trim, dormers or a cross-gable, and sometimes diamond-pane windows. Are these decorated sub-styles still part of the canon of Modern Architecture? In many ways, they are more Post-Modern than Modern, but that distinction is worthy of an involved discussion of its own.

Ranch style architecture is the style that architecture critics have generally spurned, since houses were often constructed by contractors without architect’s involvement. Ranch buildings are broad, one-story, and horizontal in overall proportion. They have an attached garage which faces the street and is part of the overall form of the house, and almost always a large picture window facing the street as well. Cladding is used to accentuate the horizontal lines of the house, so there is often a change in material at the lower part of the front façade- brick veneer was a popular choice. Many of the sub-styles of Ranch architecture are “styled” Ranch houses, meaning that elements from another style of architecture were placed on a Ranch form building. One example is Storybook Ranch, which uses “gingerbread” trim, dormers or a cross-gable, and sometimes diamond-pane windows. Are these decorated sub-styles still part of the canon of Modern Architecture? In many ways, they are more Post-Modern than Modern, but that distinction is worthy of an involved discussion of its own.  The Olympia Mid-Century Residential survey found over half the resources surveyed to be Ranch or variants of Ranch style. 31% of the surveyed homes were identified as simply Ranch, with another 11% Early Ranch, 9% Contemporary Ranch, 4% Split-Level or Split-Entry, and 4% one of the “Styled” Ranch variations. Sheer numbers alone remind us that the Ranch is deserving of study and shows us how the majority of middle-class Americans lived. As Alan Hess writes in his book Ranch House,

The Olympia Mid-Century Residential survey found over half the resources surveyed to be Ranch or variants of Ranch style. 31% of the surveyed homes were identified as simply Ranch, with another 11% Early Ranch, 9% Contemporary Ranch, 4% Split-Level or Split-Entry, and 4% one of the “Styled” Ranch variations. Sheer numbers alone remind us that the Ranch is deserving of study and shows us how the majority of middle-class Americans lived. As Alan Hess writes in his book Ranch House,

Presently, the City of Portland awarded a contract for Spectator Facilities Construction Project Management Services for a yet unnamed Veterans Memorial Coliseum project. The city is preparing for potential renovation scenarios. The uncertain future of the Coliseum feels like déjà vu.

Presently, the City of Portland awarded a contract for Spectator Facilities Construction Project Management Services for a yet unnamed Veterans Memorial Coliseum project. The city is preparing for potential renovation scenarios. The uncertain future of the Coliseum feels like déjà vu.