The terms ‘Sustainability’, ‘Green Building’, ‘Environmental Design’, and other similar phrases have recently become critical in how we approach and understand contemporary architecture. As concerns over pollution, global warming, and our impact on the surrounding environment have gained traction – we have begun to understand the building industry’s contribution to these issues. The US Green Building Council reports that buildings account for 39% of all carbon emissions in the United States, surpassing both industry and transportation.

At the core of the issue is how architects, clients, and the public imagine buildings should function and operate; a vision which has transformed over the last two centuries as technological advances have developed the capabilities of the building industry. In the last two centuries, buildings have become monuments to the Industrial and Technological Revolutions. The development of electrification, central heating, air conditioning, steel and concrete have transformed how architects design and how users function within the built environment. This shift has transformed architecture from an inherently sustainable practice into a much more complex and often unresponsive process.

While the phrase ‘sustainability’ has only recently been associated with architecture, many historic buildings were designed by incorporating sustainable practices. Without electricity, buildings by necessity had to respond to site orientation and the local climate. Natural ventilation was used to passively cool buildings, well placed windows provided natural light, and construction methods varied by location to provide an appropriate level of protection from the surrounding environment. However, as a result of modern renovations, these sustainable attributes are not always utilized to their fullest potential.

Historically, large, operable windows were an integral component of architecture in moderate climates like the Pacific Northwest. The glazing provided natural daylight while the operability allowed users to ventilate spaces based on thermal comfort. Today, the operability of windows in many historic buildings has been compromised for a variety of reasons:

• Windows that have been fixed shut to prevent users from overriding the central air system.

• Broken window hardware that hasn’t been properly maintained.

• Windows that have been painted shut.

• Windows that have been fixed shut to minimize maintenance.

Without the natural ventilation that was incorporated into the original design, these historic structures often overheat and/or rely heavily on central air conditioning. One must question why the inherent sustainability of these historic structures was compromised. Was it simply our initial infatuation with mechanical heating/cooling systems? As passive sustainable design gains traction it is critical that we understand the capabilities of historic structures in regards to their inherent sustainability.

For further investigation we have identified a case study that explores the possible impact reintegrating natural ventilation may have on thermal comfort. Trinity Episcopal Cathedral in Portland, Oregon was built in 1906 and the original design included 10 operable dormers along the Sanctuary roof. The dormers have since been boarded over, preventing rising heat from escaping. Congregants find the space overheated during the summer months and one must question whether operable dormers would provide adequate ventilation to sufficiently cool the space.

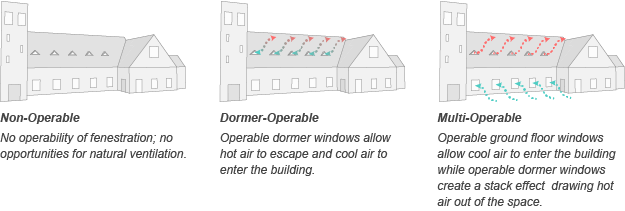

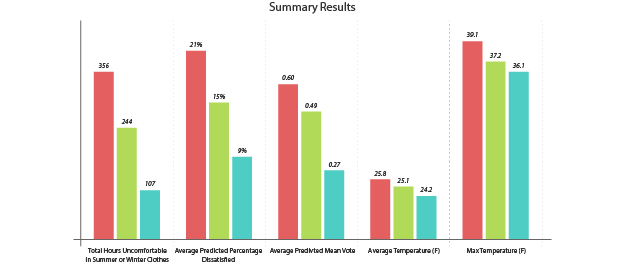

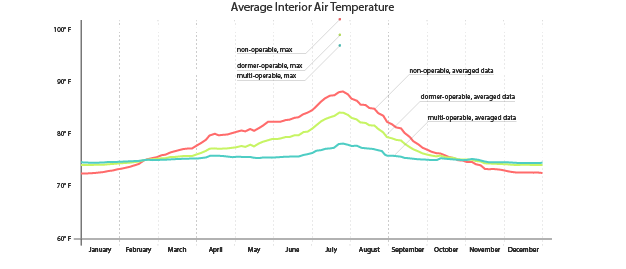

An energy model has been developed using OpenStudio and EnergyPlus to compare the thermal comfort of occupants within the space. A baseline model mimics the existing conditions and provides a comparison for the two different natural ventilation configurations. One natural ventilation configuration re-introduces the operable roof dormers to vent hot rising air. The other natural ventilation configuration re-introduces the operable roof dormers and integrates additional ventilation at the exterior wall of the building to produce stack ventilation.

While the project is still in process, initial results indicate that natural ventilation could have a significant impact on the space. The study has focused on the thermal comfort within the Sanctuary and results show that natural ventilation could dramatically lower indoor temperatures during peak summer months.

The results continue to be fine-tuned, and further refinement of the energy model will include:

• Adjusting schedules/systems to more closely reflect the building’s occupancy.

• More accurately defining the exterior infiltration rates.

• Exploring more relevant solutions for integrating stack ventilation that don’t require the large operable exterior windows. For example integrating ventilation through the basement into the main sanctuary.

While further research remains to be done, initial results are promising and demonstrate the inherent sustainability of the structure. While each building is unique, this Case Study shows how reintegration of natural ventilation may be a viable solution for passive cooling in uncomfortably warm historic buildings. Continue to check back for updates as we refine our study and explore how re-integration of natural ventilation may result in energy savings!

Written by Halla Hoffer, Architect I

Washington Park Reservoirs is a historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It was developed to store and distribute clean drinking water, but it had another important function which drove its design: it was a recreational destination for a growing urban population. At the end of the 19th Century, the City Beautiful movement across American cities inspired planners and politicians to create parks as refuges from urban life. Parks were seen as restorative, where citizens could breathe fresh air, stroll along paths or promenades, and view natural plants, lakes, and garden vistas. Many of our most famous American parks were developed during the City Beautiful era, including Central Park in New York City.

Washington Park Reservoirs is a historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It was developed to store and distribute clean drinking water, but it had another important function which drove its design: it was a recreational destination for a growing urban population. At the end of the 19th Century, the City Beautiful movement across American cities inspired planners and politicians to create parks as refuges from urban life. Parks were seen as restorative, where citizens could breathe fresh air, stroll along paths or promenades, and view natural plants, lakes, and garden vistas. Many of our most famous American parks were developed during the City Beautiful era, including Central Park in New York City.

The Washington Park Reservoir area shows the most profound shift in use over time. The need to cover and further protect drinking water in underground storage contains in lieu of open Reservoirs reflects a growing national divide between government and the public made visible by current limited access to a once prominent bucolic public destination. Perhaps a certain level of distrust is to be expected from decisions affecting public safety, but the potential loss of the Reservoirs as a contemplative, experiential destination is in stark contrast to the one of original design intent. Part of the current limited access results from the explosion in liability, where government agencies can and will be found at fault for any harm that might befall a park user or a water consumer. Federal regulations requiring municipal drinking water to be covered also feed our collective sense that there are malicious people among us.

The Washington Park Reservoir area shows the most profound shift in use over time. The need to cover and further protect drinking water in underground storage contains in lieu of open Reservoirs reflects a growing national divide between government and the public made visible by current limited access to a once prominent bucolic public destination. Perhaps a certain level of distrust is to be expected from decisions affecting public safety, but the potential loss of the Reservoirs as a contemplative, experiential destination is in stark contrast to the one of original design intent. Part of the current limited access results from the explosion in liability, where government agencies can and will be found at fault for any harm that might befall a park user or a water consumer. Federal regulations requiring municipal drinking water to be covered also feed our collective sense that there are malicious people among us.  Amazingly, the Halprin Open Space Sequence continues to survive the “age of liability” with its wonderful interactive fountains, plazas, and pools intact. Nothing this fun- and potentially hazardous- will likely be constructed again as a public project. The design reminds us that we must be responsible for protecting this level of freedom, and that this very public- and yes, democratic- open space, is uniquely valuable as a symbol of public trust.

Amazingly, the Halprin Open Space Sequence continues to survive the “age of liability” with its wonderful interactive fountains, plazas, and pools intact. Nothing this fun- and potentially hazardous- will likely be constructed again as a public project. The design reminds us that we must be responsible for protecting this level of freedom, and that this very public- and yes, democratic- open space, is uniquely valuable as a symbol of public trust.

Space programming respected the historic floor plan and scale of the original structure and recreated Yeon’s original design intent of integrating indoor space with outdoor space. Extraneous equipment and unsympathetic additions were removed from both the interior and exterior. Interior design elements, furniture, and fixtures maintain the open gallery spacial quality while integrating new furniture and fixtures meeting the needs of the tenant. Major preservation focused on the exterior restoring original paint colors through serration studies, restoring building signage in original type style and design, preserving original wood windows, when present, and restoring the intimate courtyard with a restored operating water feature.

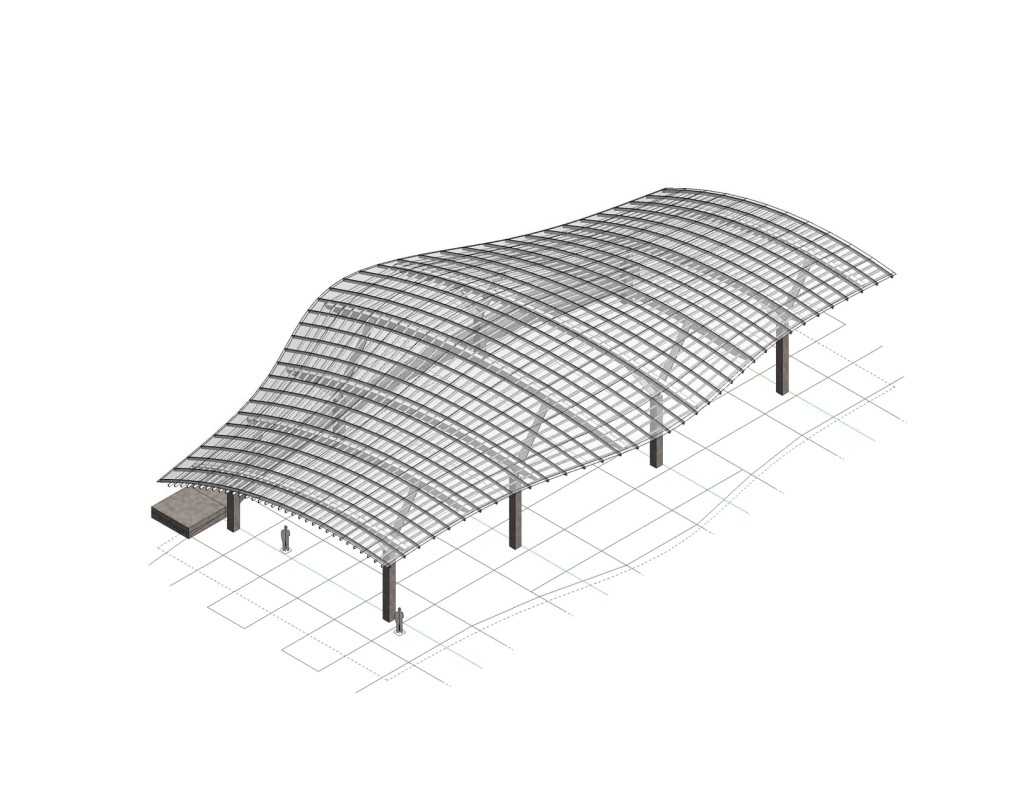

Space programming respected the historic floor plan and scale of the original structure and recreated Yeon’s original design intent of integrating indoor space with outdoor space. Extraneous equipment and unsympathetic additions were removed from both the interior and exterior. Interior design elements, furniture, and fixtures maintain the open gallery spacial quality while integrating new furniture and fixtures meeting the needs of the tenant. Major preservation focused on the exterior restoring original paint colors through serration studies, restoring building signage in original type style and design, preserving original wood windows, when present, and restoring the intimate courtyard with a restored operating water feature. Moore, Lyndon, Turnbull & Whitaker’s 1965 Pavilion at Lawrence Halprin’s Lovejoy Fountain is a whimsical all wood structure with a copper shingle roof. Although a small structure, the pavilion represents a major mid-transitional work for Charles Moore as his design style moved from mid-century modern to Post-modern design. In keeping with the naturalistic design aesthetic established by Halprin, northwest wood species comprise the major structural system including the roof trusses, vertical post supports, and vertical cribs built from 2 x 4 members laid on their side and stacked.

Moore, Lyndon, Turnbull & Whitaker’s 1965 Pavilion at Lawrence Halprin’s Lovejoy Fountain is a whimsical all wood structure with a copper shingle roof. Although a small structure, the pavilion represents a major mid-transitional work for Charles Moore as his design style moved from mid-century modern to Post-modern design. In keeping with the naturalistic design aesthetic established by Halprin, northwest wood species comprise the major structural system including the roof trusses, vertical post supports, and vertical cribs built from 2 x 4 members laid on their side and stacked. The restoration approach is intended to correct the structural deficiencies and replace the failed members with no changes to the historic appearance of the structure. The crib design allows for insertion of new steel elements, invisible from the exterior, capable of providing additional support for vertical loads. The difficulty arises because standard wood products available today have different visible and strength attributes from standard components available in 1965. Sourcing appropriate lumber is dependent upon clear and quantifiable specification, high quality inspection, and visual qualities. There are no structural standards for reclaimed or recycled lumber compounding the incorporation of “old growth” lumber as part of a new structural system. When original source material is no longer available, best practices for narrowing the selection of new materials will of necessity be combined with subjective visual qualities and a best-guess scenario as to how the new material will age in place similarly to the historic material. There are no single solutions so experience is key.

The restoration approach is intended to correct the structural deficiencies and replace the failed members with no changes to the historic appearance of the structure. The crib design allows for insertion of new steel elements, invisible from the exterior, capable of providing additional support for vertical loads. The difficulty arises because standard wood products available today have different visible and strength attributes from standard components available in 1965. Sourcing appropriate lumber is dependent upon clear and quantifiable specification, high quality inspection, and visual qualities. There are no structural standards for reclaimed or recycled lumber compounding the incorporation of “old growth” lumber as part of a new structural system. When original source material is no longer available, best practices for narrowing the selection of new materials will of necessity be combined with subjective visual qualities and a best-guess scenario as to how the new material will age in place similarly to the historic material. There are no single solutions so experience is key. Case Study 3

Case Study 3

The reservoirs embody the challenge associated with retaining a historic place as both a visual element and a dynamic landscape. The safety, security and seismic solutions may alter the purpose of the visual feature and the interaction with the “water,” but that does not translate into a diminishing of a historic place. There are no easy answers. In the end, this final decision should be assuring that the Washington Park Reservoirs will continue to provide safe, reliable water storage, and to elicit wonder well beyond the next 100 years.

The reservoirs embody the challenge associated with retaining a historic place as both a visual element and a dynamic landscape. The safety, security and seismic solutions may alter the purpose of the visual feature and the interaction with the “water,” but that does not translate into a diminishing of a historic place. There are no easy answers. In the end, this final decision should be assuring that the Washington Park Reservoirs will continue to provide safe, reliable water storage, and to elicit wonder well beyond the next 100 years.

There is still much work to be done. The Pittock Mansion Society has identified the top priority projects ranging from the practical structural and electrical work to additional programming and preservation projects. The Centennial celebration will be a grand formal affair, fitting for such a magnificent and unique cultural icon within the City of Portland’s stewardship.

There is still much work to be done. The Pittock Mansion Society has identified the top priority projects ranging from the practical structural and electrical work to additional programming and preservation projects. The Centennial celebration will be a grand formal affair, fitting for such a magnificent and unique cultural icon within the City of Portland’s stewardship.

For more information about this exciting project, including a list of buildings for intensive research, mid-century modern properties, city map with property locations, and property descriptions. Visit:

For more information about this exciting project, including a list of buildings for intensive research, mid-century modern properties, city map with property locations, and property descriptions. Visit:

These studies combined with documented field assessments and field evidence of older structures surviving earthquakes and repeated ground motion disturbances over several hundred years are available in numerous communities and offer case study structures for further research. The numbers of university engineering departments with “shake tables” (e.g. Portland State University) create opportunities for joint partnership with private sector consultants, public agencies, and professional organizations to assess and analyze the unique aspects of archaic building materials and methodologies for seismic response. The collaboration between university and private cooperation for seismic research has the potential to develop a wealth of practical and applicable information. The current collaborative efforts involving energy consumption offer the model from which to base seismic research.

These studies combined with documented field assessments and field evidence of older structures surviving earthquakes and repeated ground motion disturbances over several hundred years are available in numerous communities and offer case study structures for further research. The numbers of university engineering departments with “shake tables” (e.g. Portland State University) create opportunities for joint partnership with private sector consultants, public agencies, and professional organizations to assess and analyze the unique aspects of archaic building materials and methodologies for seismic response. The collaboration between university and private cooperation for seismic research has the potential to develop a wealth of practical and applicable information. The current collaborative efforts involving energy consumption offer the model from which to base seismic research.

When replacement units are not required and the scope is limited to on-site repair, labor costs exceed material costs. Since many historic terra cotta units were specialty designed and installed for the structure, a premium price is paid for replacement. New exterior decorative terra cotta is available only from the sources referenced and with small quantity orders, the first unit is approximately $5,000 with much of the costs attributed to making the form and determining the finish color and texture. Subsequent costs per unit will decrease with the range of decrease dependent upon quantities required.

When replacement units are not required and the scope is limited to on-site repair, labor costs exceed material costs. Since many historic terra cotta units were specialty designed and installed for the structure, a premium price is paid for replacement. New exterior decorative terra cotta is available only from the sources referenced and with small quantity orders, the first unit is approximately $5,000 with much of the costs attributed to making the form and determining the finish color and texture. Subsequent costs per unit will decrease with the range of decrease dependent upon quantities required.