The origin of Structural Brick Veneer Panel dates back to the early sixties when new “tensile strength intensive” exotic mortar combined with steel reinforcing to create a 4-inch thick, single wythe brick panel. Developments continued to occur throughout the 1960s and 1970s, peaking in use during the 1980s. The system was relatively expensive due to the use of the high tensile strength mortar.

Developments in both the high tensile strength mortar and the clay units continued to reduce cost and allow the use of regular reinforcing and standard mortar and grout. Newer systems and manufacturing processes accommodated both horizontal and vertical reinforcing and permitted high-lift grouting. Later advancements in the connections of the brick veneer panel system to the building frame resulted in the use of brick veneer panels system on multi-story high-rise office buildings, schools, apartment buildings, residences and many other applications throughout the United States and the Pacific Northwest.

Major Failure Mechanisms

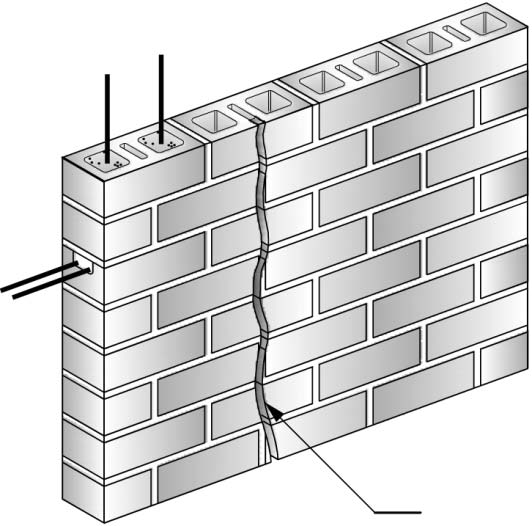

There are two major failure mechanisms of Structural Brick Veneer Panels: water intrusion and mortar/grout additives. Water intrusion can occur from a lack of adequate flashing at the window head and sill interface, carbonization of the mortar, and structural cracking. Brick veneer panels are commonly designed to allow for limited cracking at the horizontal bed joints at the brick to mortar interface. Masonry veneer panels leak more through the mortar and brick interface than through the masonry unit itself. If the mortar and brick interface is cracked, as is permitted under structural design calculations, water infiltration will increase. A cement based material, panel mortar will carbonize over time decreasing the protective alkalinity environment surrounding the reinforcing bar and thus increasing the potential for corrosion. The largest volume of water intrusion is typically associated with inadequate window systems that fail to keep water out of both the structural brick veneer panel and the cavity interface.

The durability of the wall is highly influenced by the quality of the mortar joints and interior cell grout. The specification should require reconsolidation of the grout or the incorporation of additives that balance expanding, retarding, and water reducing agents to provide a slow, controlled expansion prior to the grout hardening. Mortar/grout additives, particularly those developed in the 1970s, containing vinylidene chloride can initiate and accelerate reinforcing steel corrosion under the right conditions. The composition of the mortar/grout is determined through laboratory analysis of chloride content, vinylidene chloride, and pH level.

Repairs to structural brick veneer panels is labor intensive and may involve panel replacement, panel encapsulation, window system replacement, and/or extensive individual masonry unit repair.

Written by Peter Meijer AIA,NCARB, Principal

—————

Acknowledgement: Tawresey, John G. & John M. Hochwalt, KPFF Structural Engineers, Design Guide for Structural Brick Veneer, 3rd Ed, Western State Clay Products Association

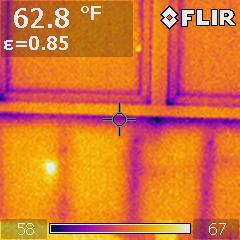

Infrared camera analysis adds another diagnostic layer of evaluation data. Temperature differentials between wet and dry surfaces can collaborate other visual observations. However, a number of varying conditions, not just water, can cause temperature differences between materials or even temperature differences within the same material. For instance, an exterior stucco wall installed over steel studs may have extreme temperature changes as a result of heat conductance through the steel studs with no related water intrusion.

Infrared camera analysis adds another diagnostic layer of evaluation data. Temperature differentials between wet and dry surfaces can collaborate other visual observations. However, a number of varying conditions, not just water, can cause temperature differences between materials or even temperature differences within the same material. For instance, an exterior stucco wall installed over steel studs may have extreme temperature changes as a result of heat conductance through the steel studs with no related water intrusion.

The balance is the most recognizable symbol, symbolizing justice. It follows that since the U.S. Custom House was built for the U.S. Custom Services, which played a significant role in the economic growth of the area, architectural ornamentation of the symbol of justice would be included. This symbol tells the audience that all services by its governing body will be conducted justly. The key is borrowed from a Christian symbol which references the bureaucratic nature of Saint Peter’s ability to grant or withhold salvation. This symbol was common in architectural ornamentation in the sixteenth-century, when politics and religion were heavily and most complicatedly intertwined. Perhaps the keys are meant to remind those within to repent, but more likely serve as an emblem of time and removers of obstacles- which are also emblems of the Roman God Janis.

The balance is the most recognizable symbol, symbolizing justice. It follows that since the U.S. Custom House was built for the U.S. Custom Services, which played a significant role in the economic growth of the area, architectural ornamentation of the symbol of justice would be included. This symbol tells the audience that all services by its governing body will be conducted justly. The key is borrowed from a Christian symbol which references the bureaucratic nature of Saint Peter’s ability to grant or withhold salvation. This symbol was common in architectural ornamentation in the sixteenth-century, when politics and religion were heavily and most complicatedly intertwined. Perhaps the keys are meant to remind those within to repent, but more likely serve as an emblem of time and removers of obstacles- which are also emblems of the Roman God Janis.  Portland’s U.S. Custom House is unquestionably one of Portland’s finest historic structures. It is an exquisite display of the Italian Renaissance Revival style of architecture with a symmetrical organization, use of terra-cotta, Roman brick, and granite materials, classically engaged Doric, Iconic, and Corinthian Columns, and displays of richly detailed architectural ornamentation found throughout the Gibbs-Surround. While it has been said the allegorical symbolic ornamentation used on U.S. Custom House is without significance and merely decorative, the explanation of each symbol has led to the credible reason for the inclusion of all these symbols. For the architecture of Portland’s U.S. Custom House is in the Italian Renaissance style, a style that uses symbolic ornamentation to signify both emotion and reason.

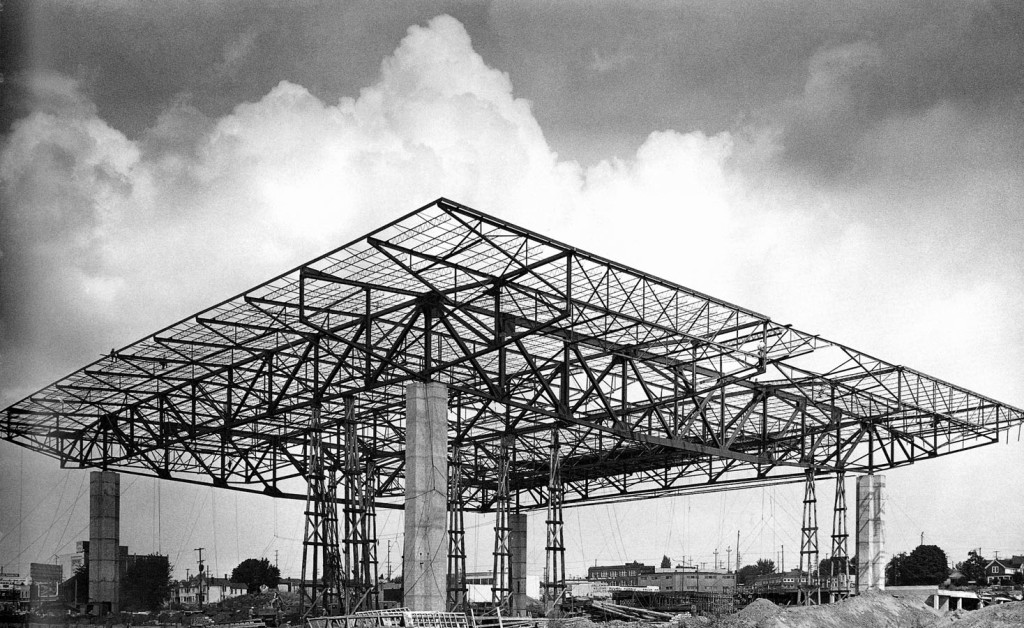

Portland’s U.S. Custom House is unquestionably one of Portland’s finest historic structures. It is an exquisite display of the Italian Renaissance Revival style of architecture with a symmetrical organization, use of terra-cotta, Roman brick, and granite materials, classically engaged Doric, Iconic, and Corinthian Columns, and displays of richly detailed architectural ornamentation found throughout the Gibbs-Surround. While it has been said the allegorical symbolic ornamentation used on U.S. Custom House is without significance and merely decorative, the explanation of each symbol has led to the credible reason for the inclusion of all these symbols. For the architecture of Portland’s U.S. Custom House is in the Italian Renaissance style, a style that uses symbolic ornamentation to signify both emotion and reason. Many of Portland’s iconic landmark buildings are modern era resources, such as the Veterans Memorial Coliseum, Lloyd Center Mall, U.S. Bancorp tower, and the Portland Building. The survey intentionally excludes these well-known properties in order to highlight broader architectural patterns and identify some of the less prominent buildings that may be considered historically significant in the future.

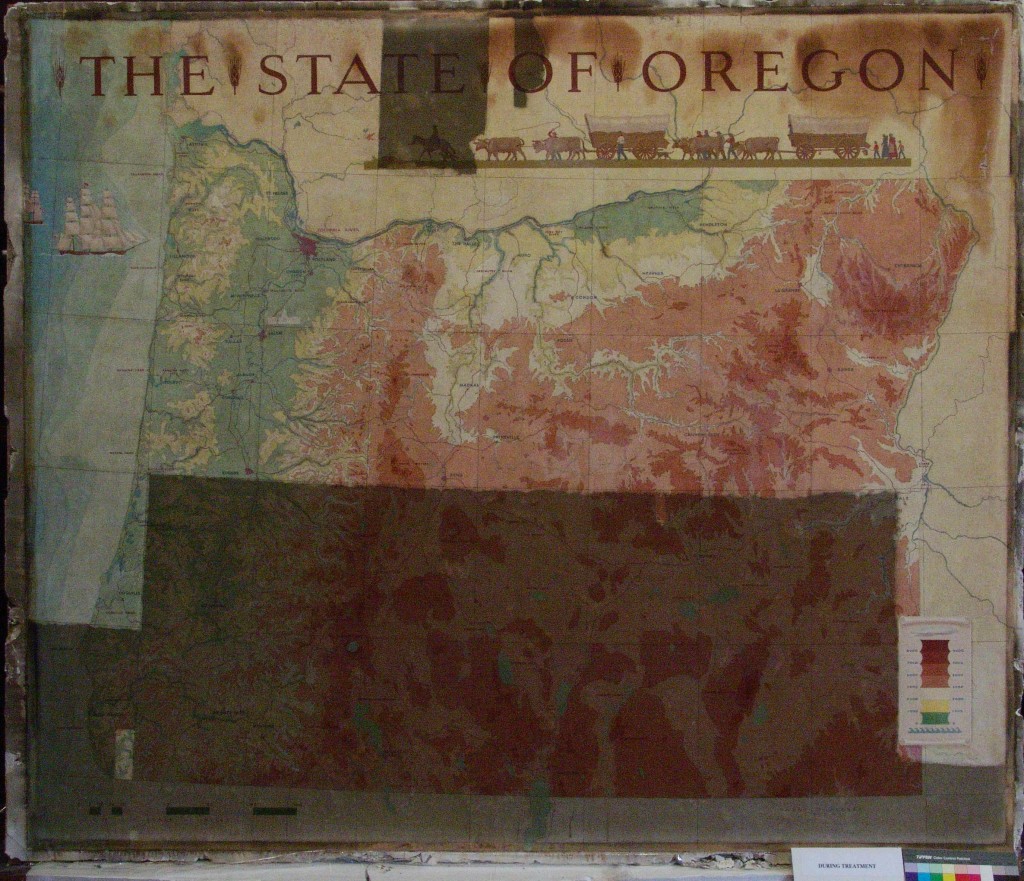

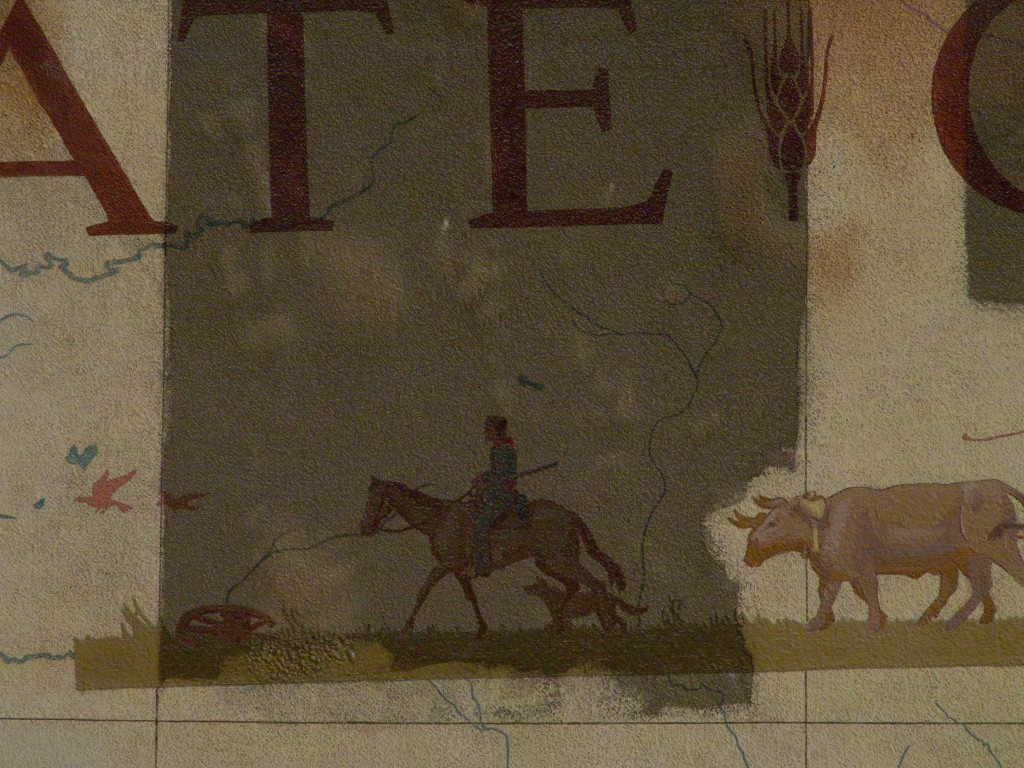

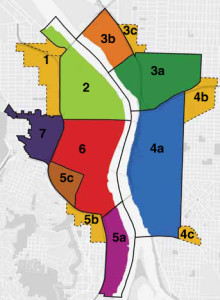

Many of Portland’s iconic landmark buildings are modern era resources, such as the Veterans Memorial Coliseum, Lloyd Center Mall, U.S. Bancorp tower, and the Portland Building. The survey intentionally excludes these well-known properties in order to highlight broader architectural patterns and identify some of the less prominent buildings that may be considered historically significant in the future. Of approximately 976 modern period resources within the Central City’s seven geographic clusters, PMA selected 152 properties for reconnaissance level survey. Representation of geographic clusters, resource typologies, and potential eligibility were considered when selecting properties to survey. In a selective survey, most properties should be considered potentially eligible for historic designation. Online maps, tax assessor information, and Google Earth were used to inform the selection process. Fieldwork involved taking photographs of each property, recording the resource type, cladding materials, style, height, plan type, and auxiliary resources, and then making a preliminary determination of National Register eligibility based on age, integrity, and historic character-defining features. A final report outlines the project and findings, and survey data was added to the Oregon Historic Sites database.

Of approximately 976 modern period resources within the Central City’s seven geographic clusters, PMA selected 152 properties for reconnaissance level survey. Representation of geographic clusters, resource typologies, and potential eligibility were considered when selecting properties to survey. In a selective survey, most properties should be considered potentially eligible for historic designation. Online maps, tax assessor information, and Google Earth were used to inform the selection process. Fieldwork involved taking photographs of each property, recording the resource type, cladding materials, style, height, plan type, and auxiliary resources, and then making a preliminary determination of National Register eligibility based on age, integrity, and historic character-defining features. A final report outlines the project and findings, and survey data was added to the Oregon Historic Sites database.

The Portland Building itself is significant as one of a handful of high-profile building designs that defined the aesthetic of Post Modern Classicism in the United States between the mid-1960s and the 1980s. Constructed in 1982, the Portland Public Service Building is nationally significant as the notable work that crystallized Michael Graves’s reputation as a master architect and as an early and seminal work of Post-Modern Classicism, an American style that Graves himself defined through his work. The structure is ground-breaking for its rejection of “universal” Modernist principles in favor of bold and symbolic color, well-defined volumes, and stylized- and reinterpreted-classical elements such as pilasters, garlands, and keystones.

The Portland Building itself is significant as one of a handful of high-profile building designs that defined the aesthetic of Post Modern Classicism in the United States between the mid-1960s and the 1980s. Constructed in 1982, the Portland Public Service Building is nationally significant as the notable work that crystallized Michael Graves’s reputation as a master architect and as an early and seminal work of Post-Modern Classicism, an American style that Graves himself defined through his work. The structure is ground-breaking for its rejection of “universal” Modernist principles in favor of bold and symbolic color, well-defined volumes, and stylized- and reinterpreted-classical elements such as pilasters, garlands, and keystones.  As one of the earliest large-scale Post-Modern buildings constructed, Graves’s design for the Portland Building was daring; almost shocking, in its vision for the future, and for its proposition as to what “after Modernism” could mean for architecture. The building itself is a fifteen-story regularly-fenestrated symmetrical monumental block clad in scored off-white colored stucco and set on a stepped two-story pedestal of blue-green tile. The building’s style is expressed through paint and applied ornament that implies classical architectural details, including terracotta tile pilasters and keystone, mirrored glass, and flattened and stylized garlands, among other elements that are intended to convey multiple meanings. For instance, the building is organized in a classical three-part division, bottom, middle, and top in reference to the human body, foot, middle, and head. At the same time, the building’s colors represent parts of the environment, with blue-green tile at the base symbolizing the earth and the light blue at the upper-most story representing the sky. The building uses layers of references to physically and symbolically tie it to place, its use, and the Western architectural tradition.

As one of the earliest large-scale Post-Modern buildings constructed, Graves’s design for the Portland Building was daring; almost shocking, in its vision for the future, and for its proposition as to what “after Modernism” could mean for architecture. The building itself is a fifteen-story regularly-fenestrated symmetrical monumental block clad in scored off-white colored stucco and set on a stepped two-story pedestal of blue-green tile. The building’s style is expressed through paint and applied ornament that implies classical architectural details, including terracotta tile pilasters and keystone, mirrored glass, and flattened and stylized garlands, among other elements that are intended to convey multiple meanings. For instance, the building is organized in a classical three-part division, bottom, middle, and top in reference to the human body, foot, middle, and head. At the same time, the building’s colors represent parts of the environment, with blue-green tile at the base symbolizing the earth and the light blue at the upper-most story representing the sky. The building uses layers of references to physically and symbolically tie it to place, its use, and the Western architectural tradition. The boxy, fifteen-story building is located in the center of downtown Portland, Oregon, occupying a full 200 by 200-foot city block right next to City Hall. The Portland Building is a surprising jolt of color within the more restrained environment and designs of nearby buildings, with its blue tile base and off-white stucco exterior accented with mirrored glass, earth-toned terracotta tile, and sky-blue penthouse. The figure of Lady Commerce from the city seal, reinterpreted by sculptor Ray Kaskey to represent a broader cultural tradition and renamed ‘Portlandia,’ is placed in front of one of the large windows as a further reference to the city. The building is notable for its regular geometry and fenestration as well as the architect’s use of over-scaled and highly-stylized classical decorative features on the building’s facades, including a copper statue mounted above the entry, garlands on the north and south facades, and the giant pilasters and keystone elements on the east and west facades. Whether or not one judges the building to be beautiful or even to have fulfilled Graves’s ideas about being humanist in nature, it is undeniably important in the history of American architecture. The building has been dispassionately evaluated in various scholarly works about the history of architecture and is inextricably linked to the rise of the Post-Modern movement.

The boxy, fifteen-story building is located in the center of downtown Portland, Oregon, occupying a full 200 by 200-foot city block right next to City Hall. The Portland Building is a surprising jolt of color within the more restrained environment and designs of nearby buildings, with its blue tile base and off-white stucco exterior accented with mirrored glass, earth-toned terracotta tile, and sky-blue penthouse. The figure of Lady Commerce from the city seal, reinterpreted by sculptor Ray Kaskey to represent a broader cultural tradition and renamed ‘Portlandia,’ is placed in front of one of the large windows as a further reference to the city. The building is notable for its regular geometry and fenestration as well as the architect’s use of over-scaled and highly-stylized classical decorative features on the building’s facades, including a copper statue mounted above the entry, garlands on the north and south facades, and the giant pilasters and keystone elements on the east and west facades. Whether or not one judges the building to be beautiful or even to have fulfilled Graves’s ideas about being humanist in nature, it is undeniably important in the history of American architecture. The building has been dispassionately evaluated in various scholarly works about the history of architecture and is inextricably linked to the rise of the Post-Modern movement.