PMA’s internship program provides students and recent graduates the opportunity to gain hands-on experience working in the dynamic fields of architecture and historic preservation. Our firm is dedicated to reinvesting into our existing built environment, with a focus on building material science and historic preservation. Since March 2021, Madison Irwin has been an intern with PMA. Her internship has focused on the intersection of net-zero research, approaches to sustainability, and historic preservation. Madison holds a Masters of Architecture from the University of Kansas and is currently completing her Masters of Science, Historic Preservation from the University of Oregon.

Describe the focus of your internship at PMA. What aspects of your internship opportunity have you enjoyed most?

I enjoyed researching materials and how they relate to new and existing buildings. I learned how old materials could be used in new ways and vice versa. How we should apply an old material in a new space brings up a lot of discussion about preservation theory and my philosophy. At PMA, I was able to learn more about this tension between old and new, and how people view them differently. Tricia, Preservation Planner, and Peter, Principal-in-Charge, made these conversations interesting. They placed these conversations within the context of Portland, Oregon.

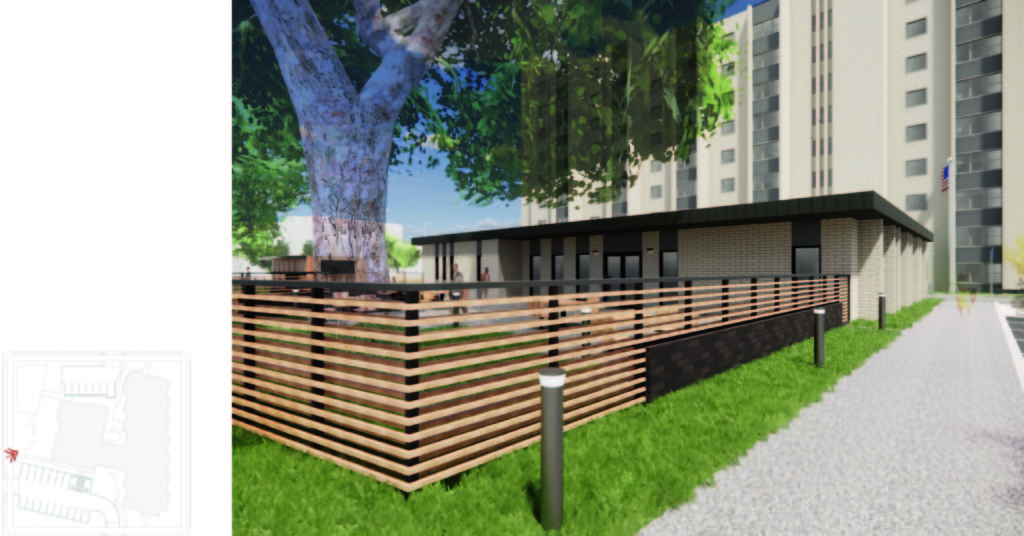

Working with Hali, Associate, and Halla, Associate-Principal, provided more of an architectural experience, especially in the realm of sustainability. The most exciting thing I researched was embodied carbon. It places the importance of using old spaces, especially if there is no reason not to use these existing spaces. It was inspirational and helped me narrow down a thesis topic for school.

Has your internship changed your perspective on historic preservation, or working with existing resources?

Yes, most definitely! It has made me more motivated to use existing places and even existing materials. There will always be a layer of history and meaning to materials, regardless of people’s care. It’s sad but true. Knowing this, I feel inspired to try and save as much as possible.

While working at PMA, I was able to work with architects and preservationists who care, very deeply, for these places that have layers of history and meaning, and there is an extra layer of sustainability and affordability that PMA advocates for. If a building means nothing to one person, the amount of carbon that was saved from being emitted or the low construction cost might be more meaningful to that person. Preservation in architecture is a way of retaining as much history as possible while making sure the resource is reused in an impactful way for the community it continues to serve.

There is more than one way to save a building and there is more than one reason to save it. It gave me a sense of opportunity.

How has your internship experience influenced your studies as you return to school to complete your thesis?

My time at PMA impacted my writing skills and how I will ultimately approach my thesis. My writing has always been something I’ve struggled with, and while I had to work through a lot of writing revisions, I also learned that it’s a forever struggle. I will always be working to improve my writing.

My thesis will look at the overlap of preservation, sustainability, and affordability, with embodied carbon being the ultimate argument to save old places. This evolved from research that I conducted at PMA.

Do you have a favorite aspect about architecture or historic preservation?

I especially love the tension between old buildings and new buildings. To see a house built in 1912 next to an ADU built in 2018 is a much more complex story. I find it more compelling than a neighborhood where everything is perfect like it was frozen in time. A layered history is more accurate to how people live their lives. Our own homes are made up of hand-me-downs from parents, grandparents; as well as the latest technologies, fashions, and books.

It sounds eclectic, it might be messy, and some people might be upset to see this new 2018 ADU in the backyard of a historic home. Some people might say, tear down the historic home! I think it comes from our society thinking that there’s no way for the two to live together. The mentality of purity is so dangerous and erases the unique, the different, the excluded.

Exploring this concept has helped me better understand how communities develop and reflect the whole history of an individual lot or a whole neighborhood. Resistance or encouragement to the ebbs and flows of developments also helps to understand the people who live in that community.

As a Kansas City native, we have to ask, what is your favorite style of BBQ?

I am unfortunately a vegetarian at the moment so I don’t get to eat my favorite, which is baby back ribs (with lots of sauce and pickles). But the grillers in KC are coming up with fun substitutes for us veggies. My favorite is a pulled jackfruit sandwich. It tastes like its own thing but is also a great replacement if you ever crave a pulled pork sandwich, with a lot of sauce, of course!

From historic to existing built infrastructure, our goal is to strengthen and enhance properties and sites that already exist. We bring together people who share our vision of delivering projects that contribute to and enhance our built environments. We are looking for individuals that share in our joy of working with owners, agencies, and other consultants, in meeting the challenges of re-investing in properties to create long-term success.

From historic to existing built infrastructure, our goal is to strengthen and enhance properties and sites that already exist. We bring together people who share our vision of delivering projects that contribute to and enhance our built environments. We are looking for individuals that share in our joy of working with owners, agencies, and other consultants, in meeting the challenges of re-investing in properties to create long-term success.

At Peter Meijer Architect, PC (PMA), we integrate Design, Science, and Preservation. Founded in 2003, PMA provides our clients with professional architectural design, building envelope science, and preservation planning services throughout the Pacific Northwest with a core focus on existing and historic buildings.

At Peter Meijer Architect, PC (PMA), we integrate Design, Science, and Preservation. Founded in 2003, PMA provides our clients with professional architectural design, building envelope science, and preservation planning services throughout the Pacific Northwest with a core focus on existing and historic buildings.