Back in April, we introduced an exciting on the boards project – Fountain Place Apartments Seismic Upgrade. Working with Lorentz Bruun Construction, we are delivering a design-build project to improve the life safety of Fountain Place Apartments, while retaining its historic character. Completed in 1914 and originally named Wheeldon Annex, Fountain Place is a five-story unreinforced brick apartment building located in downtown Portland, owned and operated by Home Forward. There are 74 total units, with studio, one-and two-bedroom homes. The unit mix is 5 at 40%, 5 at 50% and the rest restricted at 60% area median income (AMI). While the project is progressing on schedule, we will be discussing below the architectural significance of this historic resource as it relates to our built environment.

OVERVIEW

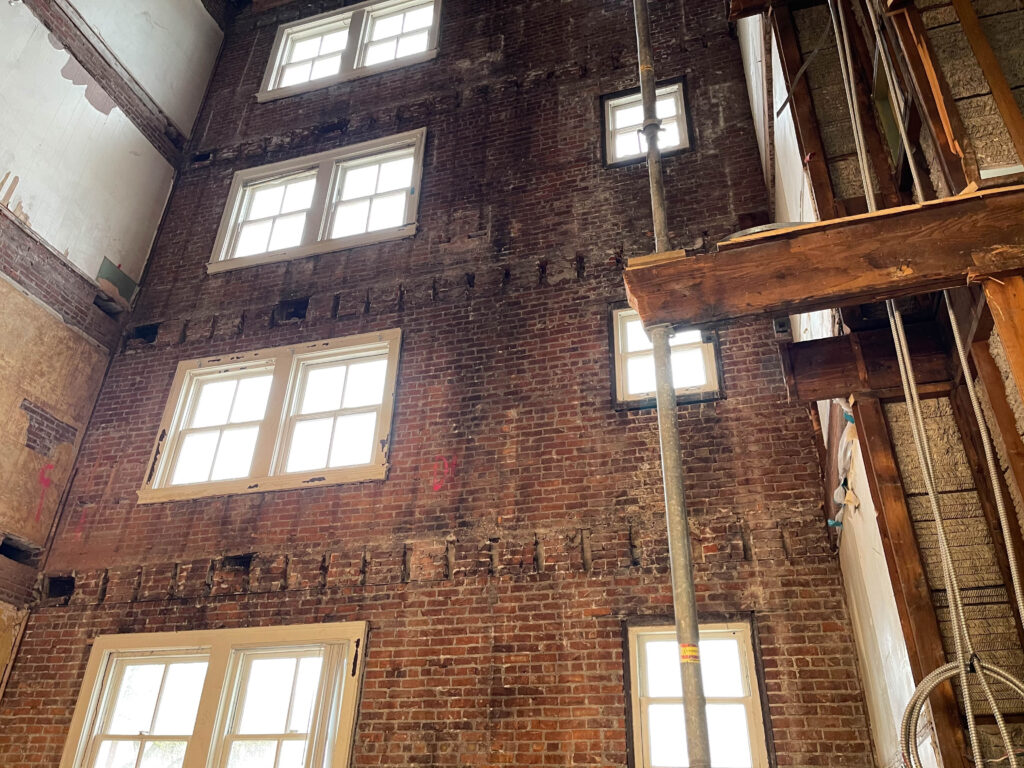

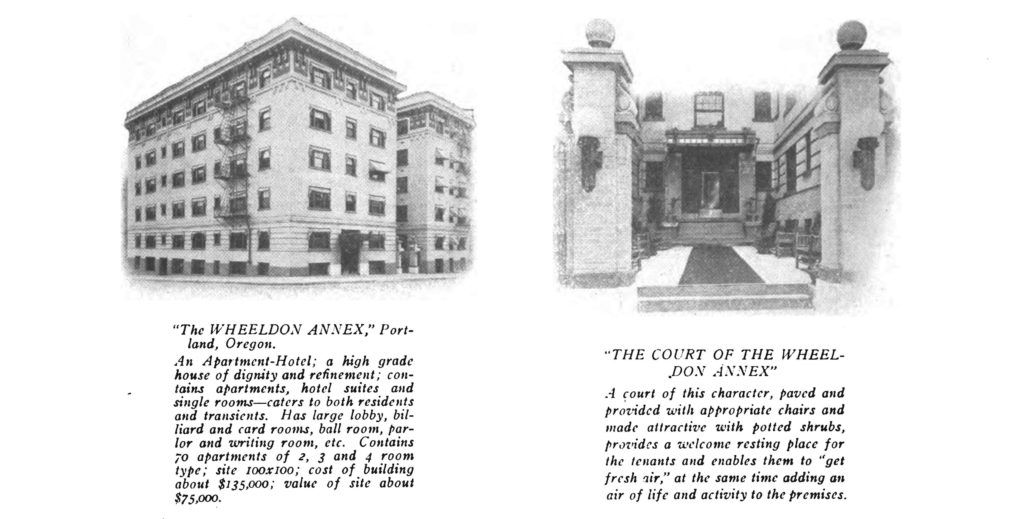

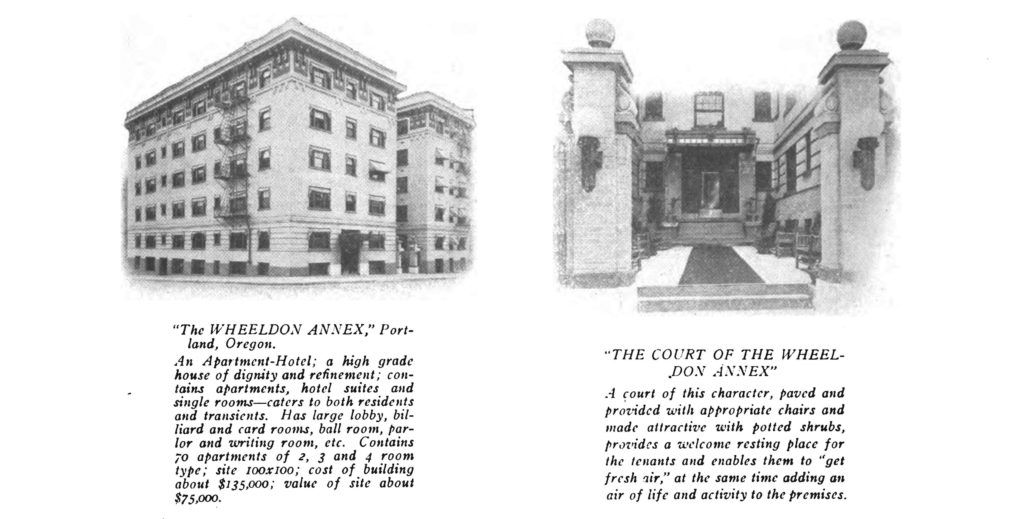

Constructed in two distinct phases in 1911, the Fountain Place Apartments were originally named the Wheeldon Annex. The building occupies a quarter-block lot in downtown Portland, Oregon, at the corner of SW Salmon Street and SW 10th Avenue. The Wheeldon Annex is one of the earliest surviving examples of a U-shaped residential apartment/hotel in downtown Portland. It is a 5-story brick structure with intact Italian Renaissance Revival features such as a decorative bracketed cornice, buff brick body with corbeled details and rusticated base, and an upper level treated as a paneled frieze. Character-defining wood double-hung multi-pane windows have been retained throughout and appear to be well maintained. Alterations to the exterior have been quite minimal.

The interior of the Wheeldon Annex has good integrity; although a number of units have been altered or divided, the general layout with U-shaped double-loaded corridors at every floor remains, and many units still contain at least some original features, materials, and layouts. These include primary rooms with original oak flooring and in some cases, the original built-in furniture with pull-out beds and fold-down desks; kitchens with wood cabinetry and trim; and bathrooms with claw foot tubs and built-in ventilation and cabinetry. While there are many units that have been divided, the alterations (primarily in the mid-1930s but continuing into the 1990s) have generally left original features in place.

The history of Wheeldon Annex is engrained in Portland’s and Oregon’s social history and practice of systemic racism. From Oregon’s statehood in 1859, the Black population were marginalized and segregated from the White population. Oregon’s State Constitution included Article 1, Section 35, “No free negro or mulatto not residing in this state at the time of the adoption of this constitution, shall come, reside or be within this state or hold any real estate, or make any contracts, or maintain any suit therein.” With the 14th and 15th Amendments, in 1868 and 1870, respectively, the Article should have been nullified, but the practices within restrictive covenants, discriminatory real estate sales, and racist zoning practices overwhelmingly prevented Black people in Oregon from accessing jobs, housing, and other vital resources.

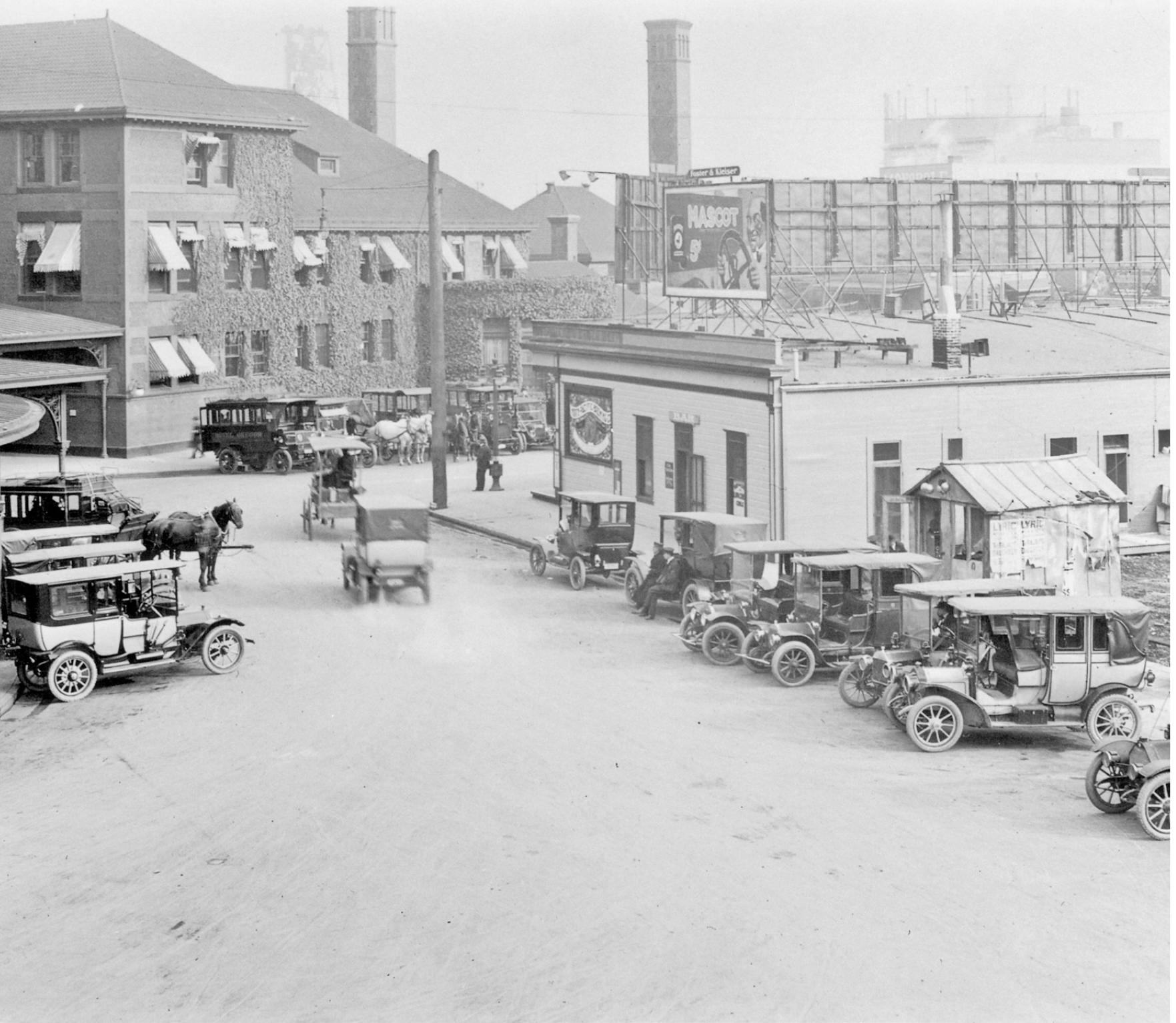

In 1910, one year before Wheeldon Annex opened, the Black population in Oregon was 1,492 while the state’s total population was 672,765. In Portland, the Black population was 775 while the city had a total of 90,246 inhabitants. The legal and systemic provisions put in place by the White majority were working to the detriment of Black people in Oregon.

DESIGN OF WHEELDON ANNEX

When Ernest MacNaughton was commissioned to design an apartment building for Frank Warren, he would have been quite familiar with the large apartment blocks built for well-off tenants on the east coast. MacNaughton’s design for the 1911 Wheeldon Annex illustrates a residential apartment block form with front courtyard protected on three sides. This form created an outdoor area but with restricted access, a pragmatic response to the more urban condition in downtown Portland.

The Wheeldon Annex, with its front entry court, appears to be among the first buildings in Portland to use a residential apartment typology in the downtown setting. There are only two earlier examples of a U-shaped apartment-style building constructed closer to downtown than those listed above; one of these is now demolished: the 1910 Beaux-Arts style Rose-Friend Apartments at 1307 SW Broadway. The other comparable downtown example pre-dating the Wheeldon Annex is the 1908 Nortonia Hotel (now Mark Spencer Hotel) at 409 SW 11th Avenue. The 6.5-story building was designed by Josef Jacobberger and has, atypically for a hotel, individual rooms along the ground floor rather than storefront with more commercial or public uses. The building exhibits a U-shaped plan with a central front pedestrian entry court and has a restrained style, with some Tudor elements and some Italian Renaissance Revival decorative touches. It is worth mentioning that there was another much larger but well-known hotel that may have been inspirational in its massing and layout. The opulent full-block Portland Hotel, which opened in 1890 and was demolished in 1951, was a 6-story building with H-shaped plan including a large forecourt for carriage drop-off.

SIGNIFICANCE

Designed by MacNaughton & Raymond for owner Frank M. Warren, the Wheeldon Annex is locally significant for its illustration of the newly acceptable, and even fashionable, shift towards high-end residential apartment living in downtown Portland. The building is one of the earliest downtown examples of a U-shaped residential apartment block form, which later proliferated across Portland, including in the downtown setting. It was completed in 1911, using a U-shaped layout first seen as early as 1907 in high-class apartments in the exclusive “Nob Hill” residential district to the west of downtown Portland. The Wheeldon Annex is associated with Portland’s exponential growth during the ten-year period starting with the Lewis and Clark Exposition. During this time, apartment buildings were introduced in Portland as a new type of construction and use targeted towards the wealthier class.

The Wheeldon Annex is also locally significant because it is a highly intact work of the well-regarded Portland architectural partnership of MacNaughton and Raymond. The building displays distinctive characteristics of the Italian Renaissance Revival style in its division into three parts; the rusticated base, middle, and decorative cornice. The Wheeldon Annex was conceived as a high-end venture; and its use of modern built-in, fold-away furniture, single bathrooms for every apartment, dumbwaiters, and tenant services gave the building a highly respectable and up-to-date reputation as soon as it was completed in 1911. While not all of these interior features, especially in individual units, are still present, the building still has good integrity overall. The building is still in its original and primary residential use, although it no longer has “hotel” functions. The building maintains its original location, design, setting, materials, and workmanship and still conveys its overall historic feeling and association.

The incredible boom in apartment and hotel construction in the first decade of the 20th century in Portland took place primarily in downtown and in northwest Portland. What is significant about the Wheeldon Annex is that it was one of the first to take the new apartment building block form, the largest and newest residential typology, and put it downtown without any ground floor commercial or significant public uses. Rather, the building featured a residential-style front courtyard. Almost all earlier forecourt apartment block examples in Portland were located significantly west of downtown. The Wheeldon Annex was constructed as an apartment-hotel, offering limited services to guests who might be permanent or temporary.

The building is locally significant for its association with the period of explosive growth starting with Portland’s Lewis and Clark Exposition in 1905. It is one of the earliest existing representations of a building typology that was to become all but ubiquitous. The size, scale, and general footprint of the building spawned hundreds of structures across Portland using a similar size, scale, and front court entry well into the 1930s. The building was designed by MacNaughton & Raymond for Frank Manley Warren, a man who made his fortune in the salmon packing and canning industry and died on the Titanic in 1912; one of only two Oregon residents to perish in the disaster. The building design features highly intact Italian Renaissance Revival exterior features such as a projecting decorative cornice with grouped brackets, a rusticated brick base, and multi-pane wood double-hung windows. It is therefore also locally significant for its architecture; as a well-crafted example of the style by a highly regarded Portland architectural firm.

MACNAUGHTON & RAYMOND ARCHITECTS

Ernest Boyd MacNaughton was an architect in Portland who practiced successfully for several decades. However, he also succeeded in becoming, through his own efforts, one of Portland’s powerful and influential banking and civic leaders. MacNaughton was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1880. MacNaughton arrived in Portland and was employed by Edgar M. Lazarus for three years until he formed his own office in 1906 with his brother-in-law, Herbert Raymond, an engineer. In 1907, only a few years after he had arrived in Portland without appreciable money or family connections, MacNaughton began to make speculative real estate transactions, riding the incredible growth in land values at that time in Portland.

In 1913, E. B. MacNaughton’s reputation took a hit when he was fired by Henry Pittock, publisher of the Oregonian. MacNaughton had been hired to renovate the Marquam building at Sixth and Morrison, but the east wall of the building collapsed when renovations were attempted and the building ultimately had to be demolished. By some accounts, the building was poorly constructed with defective materials.

By 1928, MacNaughton became involved with the First National Bank of Portland. He became president of the bank in 1932, and by 1947 chairman of the board. MacNaughton also sat in a position of leadership with many Portland institutions.

Across his design career, MacNaughton’s work shows an excellent sensitivity to scale and composition and a propensity towards a muted, 20th Century Commercial aesthetic perhaps most evident in his later warehouses. He did not have his classmate and early partner Ellis Lawrence’s facility with asymmetrical compositions or charming English styles, but MacNaughton showed a more than competent talent for the design of urban, commercial structures. Many of his buildings use tripartite “Chicago” windows, and almost all are brick.

Written by PMA staff, edited by Kate Kearney, Associate, for clarity.