During the 1960s Oregon architects, led by the Portland Archdiocese, created significant examples of unique mid‐century churches and religious structures in collaboration with local craftsman, artists, and influenced by European examples, resulting in a unique indigenous religious Modern Oregon style.

Oregon has several examples of unique mid-century churches and religious structures. Oregon is also rich in mid-century religious architecture that are unique examples of the community and/or church leadership’s interest in combining modern architecture with modern art.

During the late 1930’s Oregon architects were seeking ways to meet both the liturgical programs of their clients yet express the architecture using materials evocative of the Northwest.

Greatly influenced by the 1936 publication of John Yeon’s Watzek House, Oregon architects began to experiment with wood skins and “Mt. Hood” entry facades reminiscent of Yeon’s design. The idea that wood was symbolic of Northwest character continued through the 1950s and 1960s mid-century modern aesthetics. Local architects like Francis Jacobberger, McCoy & Bradbury, Pietro Belluschi, and others crafter their designs from outside to inside using local species of wood while simultaneously using wood to express the structural elements.

Greatly influenced by the 1936 publication of John Yeon’s Watzek House, Oregon architects began to experiment with wood skins and “Mt. Hood” entry facades reminiscent of Yeon’s design. The idea that wood was symbolic of Northwest character continued through the 1950s and 1960s mid-century modern aesthetics. Local architects like Francis Jacobberger, McCoy & Bradbury, Pietro Belluschi, and others crafter their designs from outside to inside using local species of wood while simultaneously using wood to express the structural elements.

During the 1950s and 1960s, architectural journals devoted pages and images to the increasingly innovative use of concrete as both a structural element and aesthetic material. Local Oregon firms too experimented with concrete. John Maloney’s 1950 design for St. Ignatius is executed entirely of formed concrete. The exterior, interior, and the bell tower are unabashedly presented as an aesthetic material worthy of religious structure. Maloney deliberately painted the interior white to match the exterior and emphasize the versatility and economy of concrete, the new material of choice.

Queen of Peace

One of the most unique indigenous examples of Oregon religious architecture is the Queen of Peace in north Portland. Queen of Peace combines both the engineering daring of concrete with the creative influences from local artists. Queen of Peace is created with clay, river stone, and stunning minimalist concrete structure.

Queen of Peace was influenced by Friar John Domin who served the Portland Archdiocese as a priest for 57 years, as a pastor of several parishes, a high school art teacher, and volunteer at the Art Institute of Portland. As Chairman of the Sacred Art Commission of the Archdiocese of Portland, he actively engaged in the design process of churches and chapels. He worked with architects and hired ingenious liturgical artists who worked in a variety of media to enhance churches with stunning sacred art. ” (Sanctuary for Sacred Arts website)

Well known Oregon artists, including Ray Grimm, a ceramists, created the dominating Tree of Life mosaic on the west façade. LeRoy Setziol, the “Father of Wood Carving in Oregon,” created the wood Stations of the Cross and baptismal font. Surprisingly Setziol was commissioned to execute the stained glass windows as well. And Lee Kelly, one of Portland’s best known metal sculptors, enriched the church with delicate displays of metal work both on the interior and exterior. Queen of Peace is a marvelous collaboration of architecture, art, and technical daring creating a wonderful display of Oregon indigenous mid-century religious architecture.

Well known Oregon artists, including Ray Grimm, a ceramists, created the dominating Tree of Life mosaic on the west façade. LeRoy Setziol, the “Father of Wood Carving in Oregon,” created the wood Stations of the Cross and baptismal font. Surprisingly Setziol was commissioned to execute the stained glass windows as well. And Lee Kelly, one of Portland’s best known metal sculptors, enriched the church with delicate displays of metal work both on the interior and exterior. Queen of Peace is a marvelous collaboration of architecture, art, and technical daring creating a wonderful display of Oregon indigenous mid-century religious architecture.

Written by Peter Meijer AIA, NCARB, Principal. This post is an excerpt from Peter’s presentation at this year’s DoCoMoMo_US National Symposium: Modernism on the Prairie. Peter is the President and Founder of DoCoMoMo_US Oregon Chapter. For more information, please visit: DoCoMoMo-US

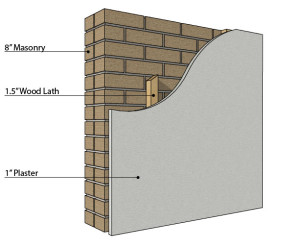

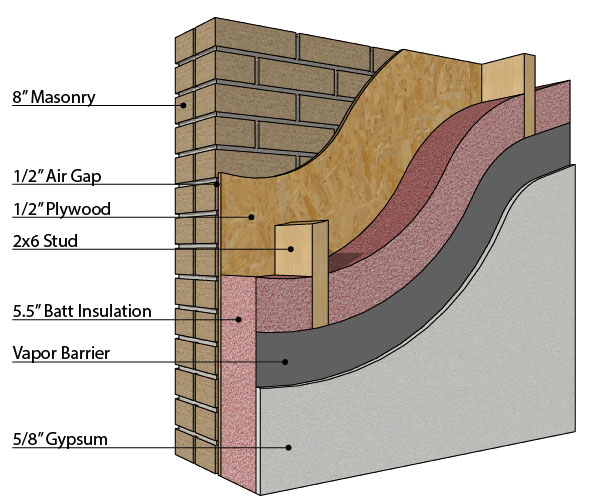

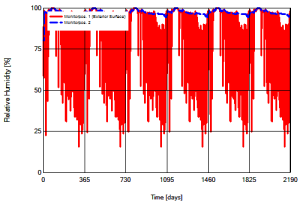

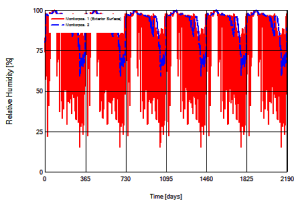

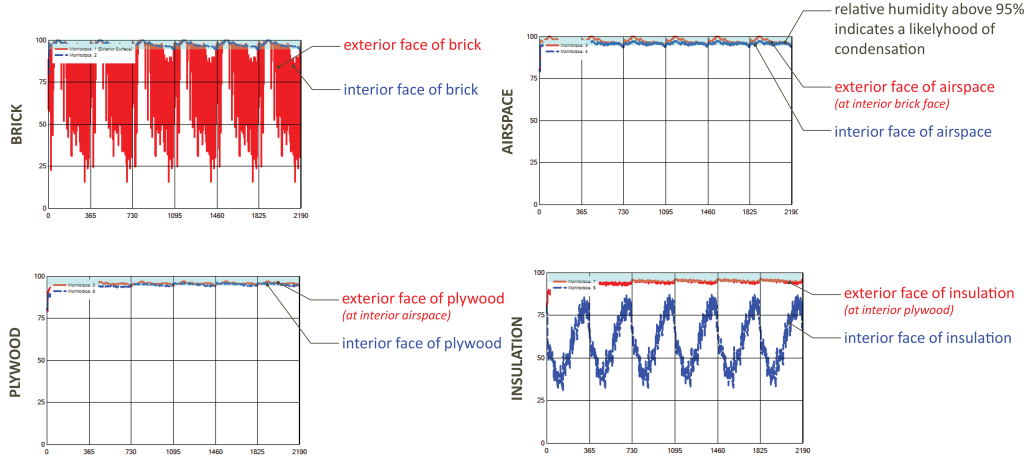

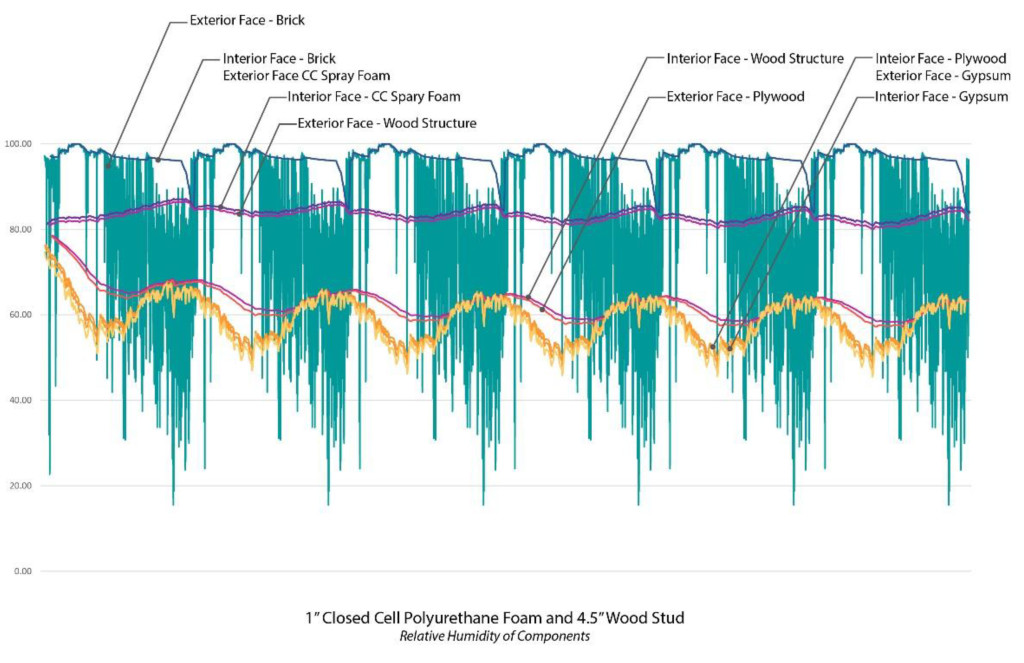

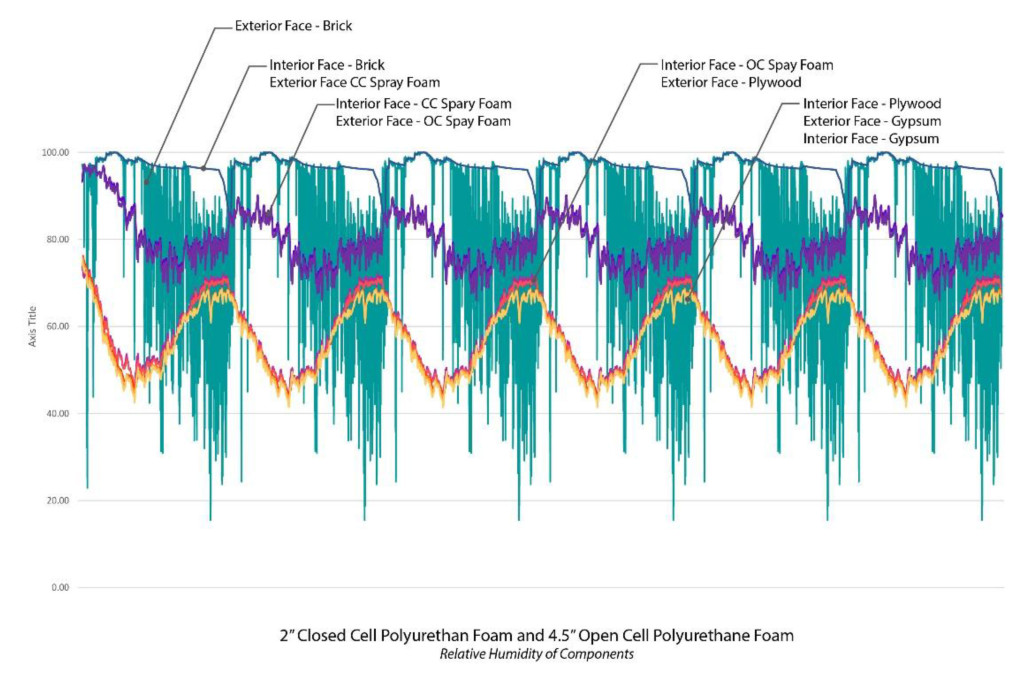

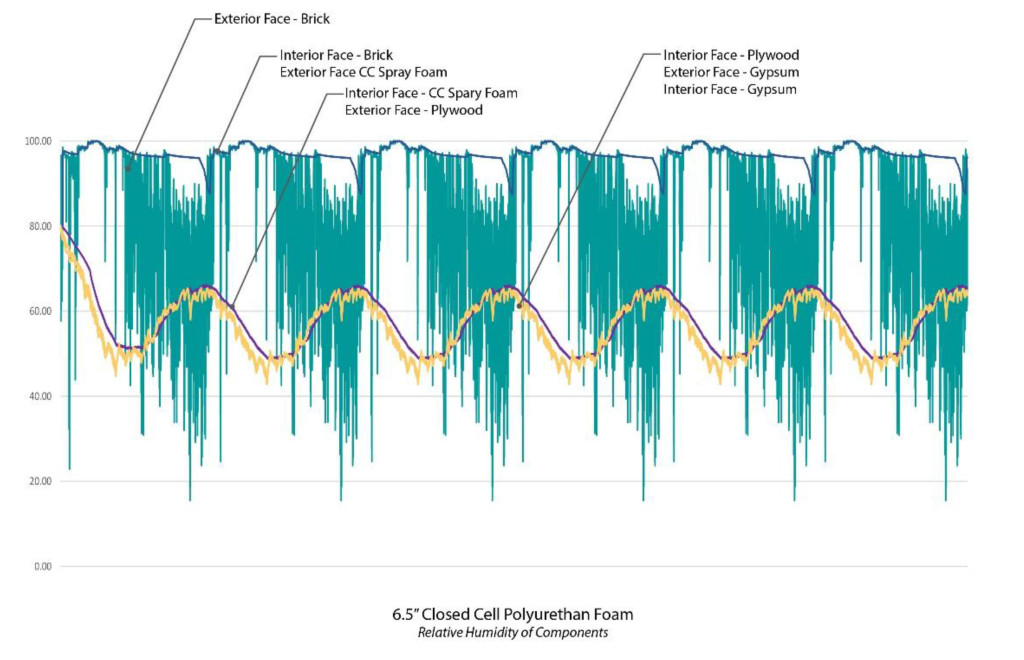

The results of the initial analysis indicated that as might be expected the masonry was not only exposed to longer periods of cool temperatures, it rarely was capable of fully drying. The two charts at the right show the relative humidity in the original construction and the proposed construction where each vertical line marks a calendar year. Note that a relative humidity above 95% indicates a likelihood of condensation. As can be seen in the original construction, during the wet months the relative humidity hovers at about 95%, but drops off significantly during the warmer months. Alternately in the proposed construction the relative humidity rarely drops below 95%, indicating that moisture is present in the masonry almost year round. When the individual layers are examined it becomes clear that in addition to considerable moisture in the masonry itself, water is likely to condense within the wall cavity. As seen in the series of charts below the relative humidity remains high through the airspace and plywood only dropping off between the exterior and interior face of the insulation.

The results of the initial analysis indicated that as might be expected the masonry was not only exposed to longer periods of cool temperatures, it rarely was capable of fully drying. The two charts at the right show the relative humidity in the original construction and the proposed construction where each vertical line marks a calendar year. Note that a relative humidity above 95% indicates a likelihood of condensation. As can be seen in the original construction, during the wet months the relative humidity hovers at about 95%, but drops off significantly during the warmer months. Alternately in the proposed construction the relative humidity rarely drops below 95%, indicating that moisture is present in the masonry almost year round. When the individual layers are examined it becomes clear that in addition to considerable moisture in the masonry itself, water is likely to condense within the wall cavity. As seen in the series of charts below the relative humidity remains high through the airspace and plywood only dropping off between the exterior and interior face of the insulation.  Given these initial results we suggested a redesign of the insulation system. The existing two wythe wall was not capable of adequately protecting the interior of the building, and the redesign had to accommodate for water infiltration through the masonry. Two options were discussed A) treat the masonry as a veneer wall and install waterproofing to the exterior face of the plywood as a drainage plane or B) install insulation that could be exposed to moisture and water. The constructability of Option A was significantly more complex than that of Option B so our initial analysis focused on Option B.

Given these initial results we suggested a redesign of the insulation system. The existing two wythe wall was not capable of adequately protecting the interior of the building, and the redesign had to accommodate for water infiltration through the masonry. Two options were discussed A) treat the masonry as a veneer wall and install waterproofing to the exterior face of the plywood as a drainage plane or B) install insulation that could be exposed to moisture and water. The constructability of Option A was significantly more complex than that of Option B so our initial analysis focused on Option B.

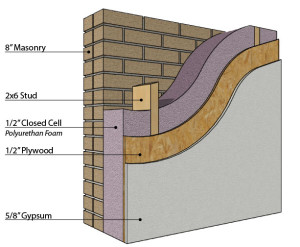

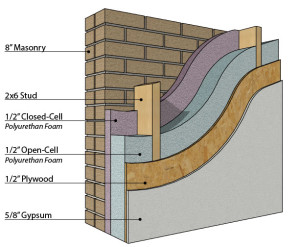

Spray foam was identified as an alternative to the original batt insulation because it can both serve as a vapor retarder and insulate even when exposed to moisture. Two design options were investigated to determine the extent of closed cell foam necessary to adequately protect the interior surfaces from moisture. As can be seen to the right we investigated a construction filled entirely with closed cell polyurethane foam vs. a cavity filled with a combination of closed and open cell polyurethanes. Additionally we looked at the condition of moisture/heat transfer at the perceived weakest point in the structure, where the structural framing was only barely (1/2”) separated from the masonry. The structural integrity of the seismic upgrade depended on a minimal distance between the framing and the existing masonry, but concerns existed as to whether the wood would be exposed to enough moisture to cause mold.

Spray foam was identified as an alternative to the original batt insulation because it can both serve as a vapor retarder and insulate even when exposed to moisture. Two design options were investigated to determine the extent of closed cell foam necessary to adequately protect the interior surfaces from moisture. As can be seen to the right we investigated a construction filled entirely with closed cell polyurethane foam vs. a cavity filled with a combination of closed and open cell polyurethanes. Additionally we looked at the condition of moisture/heat transfer at the perceived weakest point in the structure, where the structural framing was only barely (1/2”) separated from the masonry. The structural integrity of the seismic upgrade depended on a minimal distance between the framing and the existing masonry, but concerns existed as to whether the wood would be exposed to enough moisture to cause mold.

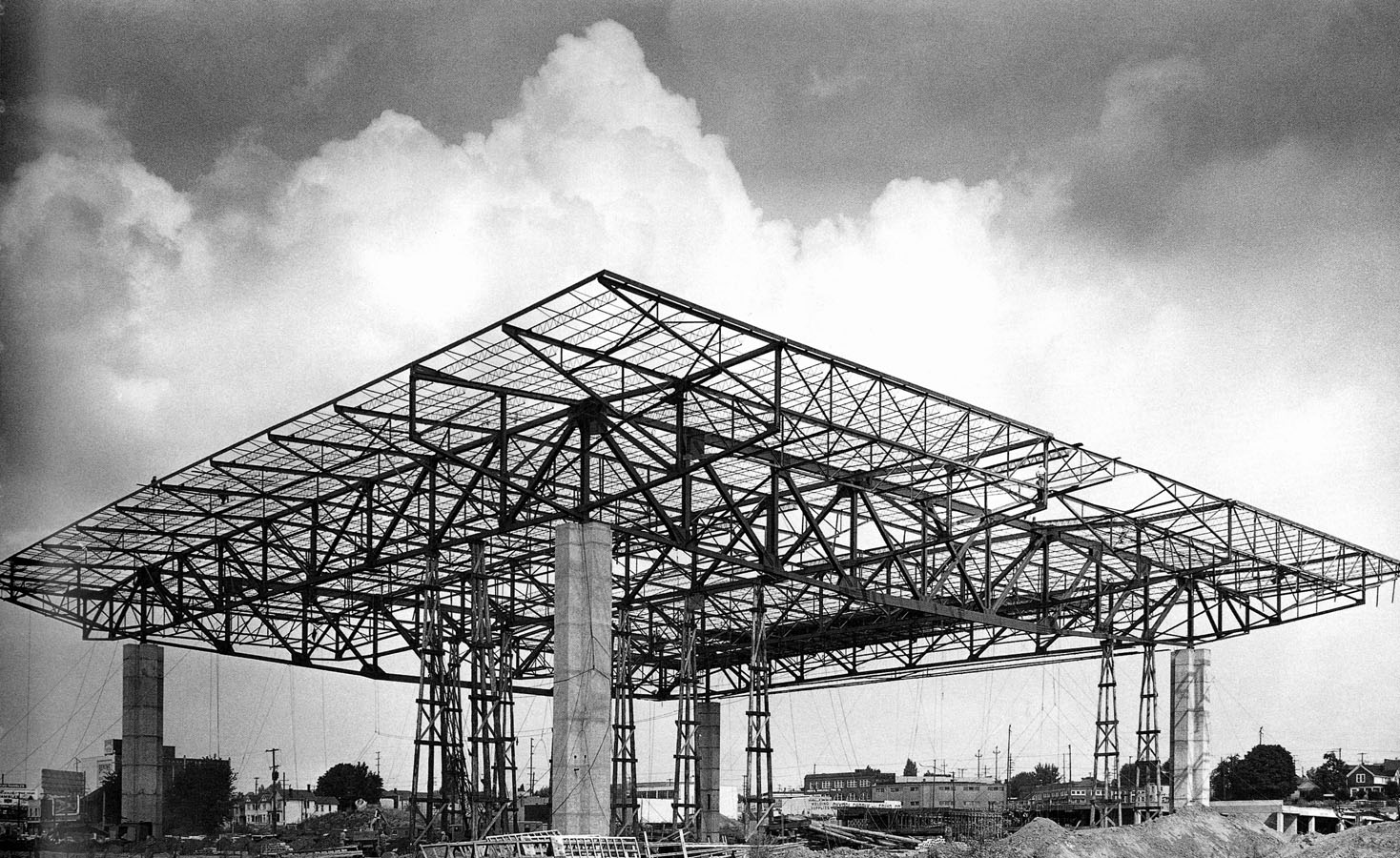

Presently, the City of Portland awarded a contract for Spectator Facilities Construction Project Management Services for a yet unnamed Veterans Memorial Coliseum project. The city is preparing for potential renovation scenarios. The uncertain future of the Coliseum feels like déjà vu.

Presently, the City of Portland awarded a contract for Spectator Facilities Construction Project Management Services for a yet unnamed Veterans Memorial Coliseum project. The city is preparing for potential renovation scenarios. The uncertain future of the Coliseum feels like déjà vu.

Space programming respected the historic floor plan and scale of the original structure and recreated Yeon’s original design intent of integrating indoor space with outdoor space. Extraneous equipment and unsympathetic additions were removed from both the interior and exterior. Interior design elements, furniture, and fixtures maintain the open gallery spacial quality while integrating new furniture and fixtures meeting the needs of the tenant. Major preservation focused on the exterior restoring original paint colors through serration studies, restoring building signage in original type style and design, preserving original wood windows, when present, and restoring the intimate courtyard with a restored operating water feature.

Space programming respected the historic floor plan and scale of the original structure and recreated Yeon’s original design intent of integrating indoor space with outdoor space. Extraneous equipment and unsympathetic additions were removed from both the interior and exterior. Interior design elements, furniture, and fixtures maintain the open gallery spacial quality while integrating new furniture and fixtures meeting the needs of the tenant. Major preservation focused on the exterior restoring original paint colors through serration studies, restoring building signage in original type style and design, preserving original wood windows, when present, and restoring the intimate courtyard with a restored operating water feature. Moore, Lyndon, Turnbull & Whitaker’s 1965 Pavilion at Lawrence Halprin’s Lovejoy Fountain is a whimsical all wood structure with a copper shingle roof. Although a small structure, the pavilion represents a major mid-transitional work for Charles Moore as his design style moved from mid-century modern to Post-modern design. In keeping with the naturalistic design aesthetic established by Halprin, northwest wood species comprise the major structural system including the roof trusses, vertical post supports, and vertical cribs built from 2 x 4 members laid on their side and stacked.

Moore, Lyndon, Turnbull & Whitaker’s 1965 Pavilion at Lawrence Halprin’s Lovejoy Fountain is a whimsical all wood structure with a copper shingle roof. Although a small structure, the pavilion represents a major mid-transitional work for Charles Moore as his design style moved from mid-century modern to Post-modern design. In keeping with the naturalistic design aesthetic established by Halprin, northwest wood species comprise the major structural system including the roof trusses, vertical post supports, and vertical cribs built from 2 x 4 members laid on their side and stacked. The restoration approach is intended to correct the structural deficiencies and replace the failed members with no changes to the historic appearance of the structure. The crib design allows for insertion of new steel elements, invisible from the exterior, capable of providing additional support for vertical loads. The difficulty arises because standard wood products available today have different visible and strength attributes from standard components available in 1965. Sourcing appropriate lumber is dependent upon clear and quantifiable specification, high quality inspection, and visual qualities. There are no structural standards for reclaimed or recycled lumber compounding the incorporation of “old growth” lumber as part of a new structural system. When original source material is no longer available, best practices for narrowing the selection of new materials will of necessity be combined with subjective visual qualities and a best-guess scenario as to how the new material will age in place similarly to the historic material. There are no single solutions so experience is key.

The restoration approach is intended to correct the structural deficiencies and replace the failed members with no changes to the historic appearance of the structure. The crib design allows for insertion of new steel elements, invisible from the exterior, capable of providing additional support for vertical loads. The difficulty arises because standard wood products available today have different visible and strength attributes from standard components available in 1965. Sourcing appropriate lumber is dependent upon clear and quantifiable specification, high quality inspection, and visual qualities. There are no structural standards for reclaimed or recycled lumber compounding the incorporation of “old growth” lumber as part of a new structural system. When original source material is no longer available, best practices for narrowing the selection of new materials will of necessity be combined with subjective visual qualities and a best-guess scenario as to how the new material will age in place similarly to the historic material. There are no single solutions so experience is key. Case Study 3

Case Study 3

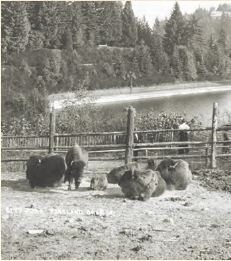

The reservoirs embody the challenge associated with retaining a historic place as both a visual element and a dynamic landscape. The safety, security and seismic solutions may alter the purpose of the visual feature and the interaction with the “water,” but that does not translate into a diminishing of a historic place. There are no easy answers. In the end, this final decision should be assuring that the Washington Park Reservoirs will continue to provide safe, reliable water storage, and to elicit wonder well beyond the next 100 years.

The reservoirs embody the challenge associated with retaining a historic place as both a visual element and a dynamic landscape. The safety, security and seismic solutions may alter the purpose of the visual feature and the interaction with the “water,” but that does not translate into a diminishing of a historic place. There are no easy answers. In the end, this final decision should be assuring that the Washington Park Reservoirs will continue to provide safe, reliable water storage, and to elicit wonder well beyond the next 100 years.

There is still much work to be done. The Pittock Mansion Society has identified the top priority projects ranging from the practical structural and electrical work to additional programming and preservation projects. The Centennial celebration will be a grand formal affair, fitting for such a magnificent and unique cultural icon within the City of Portland’s stewardship.

There is still much work to be done. The Pittock Mansion Society has identified the top priority projects ranging from the practical structural and electrical work to additional programming and preservation projects. The Centennial celebration will be a grand formal affair, fitting for such a magnificent and unique cultural icon within the City of Portland’s stewardship.

The balance is the most recognizable symbol, symbolizing justice. It follows that since the U.S. Custom House was built for the U.S. Custom Services, which played a significant role in the economic growth of the area, architectural ornamentation of the symbol of justice would be included. This symbol tells the audience that all services by its governing body will be conducted justly. The key is borrowed from a Christian symbol which references the bureaucratic nature of Saint Peter’s ability to grant or withhold salvation. This symbol was common in architectural ornamentation in the sixteenth-century, when politics and religion were heavily and most complicatedly intertwined. Perhaps the keys are meant to remind those within to repent, but more likely serve as an emblem of time and removers of obstacles- which are also emblems of the Roman God Janis.

The balance is the most recognizable symbol, symbolizing justice. It follows that since the U.S. Custom House was built for the U.S. Custom Services, which played a significant role in the economic growth of the area, architectural ornamentation of the symbol of justice would be included. This symbol tells the audience that all services by its governing body will be conducted justly. The key is borrowed from a Christian symbol which references the bureaucratic nature of Saint Peter’s ability to grant or withhold salvation. This symbol was common in architectural ornamentation in the sixteenth-century, when politics and religion were heavily and most complicatedly intertwined. Perhaps the keys are meant to remind those within to repent, but more likely serve as an emblem of time and removers of obstacles- which are also emblems of the Roman God Janis.  Portland’s U.S. Custom House is unquestionably one of Portland’s finest historic structures. It is an exquisite display of the Italian Renaissance Revival style of architecture with a symmetrical organization, use of terra-cotta, Roman brick, and granite materials, classically engaged Doric, Iconic, and Corinthian Columns, and displays of richly detailed architectural ornamentation found throughout the Gibbs-Surround. While it has been said the allegorical symbolic ornamentation used on U.S. Custom House is without significance and merely decorative, the explanation of each symbol has led to the credible reason for the inclusion of all these symbols. For the architecture of Portland’s U.S. Custom House is in the Italian Renaissance style, a style that uses symbolic ornamentation to signify both emotion and reason.

Portland’s U.S. Custom House is unquestionably one of Portland’s finest historic structures. It is an exquisite display of the Italian Renaissance Revival style of architecture with a symmetrical organization, use of terra-cotta, Roman brick, and granite materials, classically engaged Doric, Iconic, and Corinthian Columns, and displays of richly detailed architectural ornamentation found throughout the Gibbs-Surround. While it has been said the allegorical symbolic ornamentation used on U.S. Custom House is without significance and merely decorative, the explanation of each symbol has led to the credible reason for the inclusion of all these symbols. For the architecture of Portland’s U.S. Custom House is in the Italian Renaissance style, a style that uses symbolic ornamentation to signify both emotion and reason. Many of Portland’s iconic landmark buildings are modern era resources, such as the Veterans Memorial Coliseum, Lloyd Center Mall, U.S. Bancorp tower, and the Portland Building. The survey intentionally excludes these well-known properties in order to highlight broader architectural patterns and identify some of the less prominent buildings that may be considered historically significant in the future.

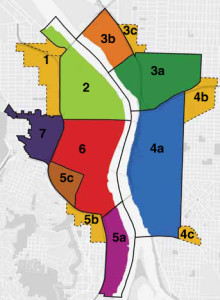

Many of Portland’s iconic landmark buildings are modern era resources, such as the Veterans Memorial Coliseum, Lloyd Center Mall, U.S. Bancorp tower, and the Portland Building. The survey intentionally excludes these well-known properties in order to highlight broader architectural patterns and identify some of the less prominent buildings that may be considered historically significant in the future. Of approximately 976 modern period resources within the Central City’s seven geographic clusters, PMA selected 152 properties for reconnaissance level survey. Representation of geographic clusters, resource typologies, and potential eligibility were considered when selecting properties to survey. In a selective survey, most properties should be considered potentially eligible for historic designation. Online maps, tax assessor information, and Google Earth were used to inform the selection process. Fieldwork involved taking photographs of each property, recording the resource type, cladding materials, style, height, plan type, and auxiliary resources, and then making a preliminary determination of National Register eligibility based on age, integrity, and historic character-defining features. A final report outlines the project and findings, and survey data was added to the Oregon Historic Sites database.

Of approximately 976 modern period resources within the Central City’s seven geographic clusters, PMA selected 152 properties for reconnaissance level survey. Representation of geographic clusters, resource typologies, and potential eligibility were considered when selecting properties to survey. In a selective survey, most properties should be considered potentially eligible for historic designation. Online maps, tax assessor information, and Google Earth were used to inform the selection process. Fieldwork involved taking photographs of each property, recording the resource type, cladding materials, style, height, plan type, and auxiliary resources, and then making a preliminary determination of National Register eligibility based on age, integrity, and historic character-defining features. A final report outlines the project and findings, and survey data was added to the Oregon Historic Sites database.

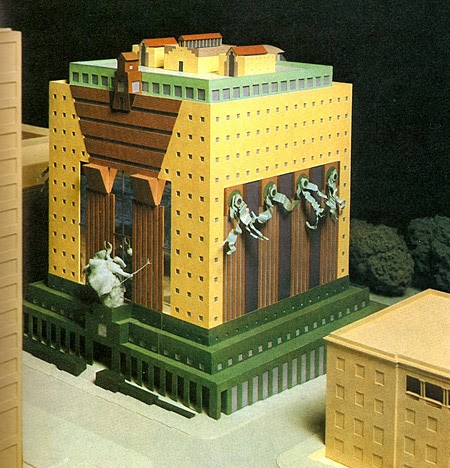

The Portland Building itself is significant as one of a handful of high-profile building designs that defined the aesthetic of Post Modern Classicism in the United States between the mid-1960s and the 1980s. Constructed in 1982, the Portland Public Service Building is nationally significant as the notable work that crystallized Michael Graves’s reputation as a master architect and as an early and seminal work of Post-Modern Classicism, an American style that Graves himself defined through his work. The structure is ground-breaking for its rejection of “universal” Modernist principles in favor of bold and symbolic color, well-defined volumes, and stylized- and reinterpreted-classical elements such as pilasters, garlands, and keystones.

The Portland Building itself is significant as one of a handful of high-profile building designs that defined the aesthetic of Post Modern Classicism in the United States between the mid-1960s and the 1980s. Constructed in 1982, the Portland Public Service Building is nationally significant as the notable work that crystallized Michael Graves’s reputation as a master architect and as an early and seminal work of Post-Modern Classicism, an American style that Graves himself defined through his work. The structure is ground-breaking for its rejection of “universal” Modernist principles in favor of bold and symbolic color, well-defined volumes, and stylized- and reinterpreted-classical elements such as pilasters, garlands, and keystones.  As one of the earliest large-scale Post-Modern buildings constructed, Graves’s design for the Portland Building was daring; almost shocking, in its vision for the future, and for its proposition as to what “after Modernism” could mean for architecture. The building itself is a fifteen-story regularly-fenestrated symmetrical monumental block clad in scored off-white colored stucco and set on a stepped two-story pedestal of blue-green tile. The building’s style is expressed through paint and applied ornament that implies classical architectural details, including terracotta tile pilasters and keystone, mirrored glass, and flattened and stylized garlands, among other elements that are intended to convey multiple meanings. For instance, the building is organized in a classical three-part division, bottom, middle, and top in reference to the human body, foot, middle, and head. At the same time, the building’s colors represent parts of the environment, with blue-green tile at the base symbolizing the earth and the light blue at the upper-most story representing the sky. The building uses layers of references to physically and symbolically tie it to place, its use, and the Western architectural tradition.

As one of the earliest large-scale Post-Modern buildings constructed, Graves’s design for the Portland Building was daring; almost shocking, in its vision for the future, and for its proposition as to what “after Modernism” could mean for architecture. The building itself is a fifteen-story regularly-fenestrated symmetrical monumental block clad in scored off-white colored stucco and set on a stepped two-story pedestal of blue-green tile. The building’s style is expressed through paint and applied ornament that implies classical architectural details, including terracotta tile pilasters and keystone, mirrored glass, and flattened and stylized garlands, among other elements that are intended to convey multiple meanings. For instance, the building is organized in a classical three-part division, bottom, middle, and top in reference to the human body, foot, middle, and head. At the same time, the building’s colors represent parts of the environment, with blue-green tile at the base symbolizing the earth and the light blue at the upper-most story representing the sky. The building uses layers of references to physically and symbolically tie it to place, its use, and the Western architectural tradition. The boxy, fifteen-story building is located in the center of downtown Portland, Oregon, occupying a full 200 by 200-foot city block right next to City Hall. The Portland Building is a surprising jolt of color within the more restrained environment and designs of nearby buildings, with its blue tile base and off-white stucco exterior accented with mirrored glass, earth-toned terracotta tile, and sky-blue penthouse. The figure of Lady Commerce from the city seal, reinterpreted by sculptor Ray Kaskey to represent a broader cultural tradition and renamed ‘Portlandia,’ is placed in front of one of the large windows as a further reference to the city. The building is notable for its regular geometry and fenestration as well as the architect’s use of over-scaled and highly-stylized classical decorative features on the building’s facades, including a copper statue mounted above the entry, garlands on the north and south facades, and the giant pilasters and keystone elements on the east and west facades. Whether or not one judges the building to be beautiful or even to have fulfilled Graves’s ideas about being humanist in nature, it is undeniably important in the history of American architecture. The building has been dispassionately evaluated in various scholarly works about the history of architecture and is inextricably linked to the rise of the Post-Modern movement.

The boxy, fifteen-story building is located in the center of downtown Portland, Oregon, occupying a full 200 by 200-foot city block right next to City Hall. The Portland Building is a surprising jolt of color within the more restrained environment and designs of nearby buildings, with its blue tile base and off-white stucco exterior accented with mirrored glass, earth-toned terracotta tile, and sky-blue penthouse. The figure of Lady Commerce from the city seal, reinterpreted by sculptor Ray Kaskey to represent a broader cultural tradition and renamed ‘Portlandia,’ is placed in front of one of the large windows as a further reference to the city. The building is notable for its regular geometry and fenestration as well as the architect’s use of over-scaled and highly-stylized classical decorative features on the building’s facades, including a copper statue mounted above the entry, garlands on the north and south facades, and the giant pilasters and keystone elements on the east and west facades. Whether or not one judges the building to be beautiful or even to have fulfilled Graves’s ideas about being humanist in nature, it is undeniably important in the history of American architecture. The building has been dispassionately evaluated in various scholarly works about the history of architecture and is inextricably linked to the rise of the Post-Modern movement.