Portland’s historic streetscapes were composed of Belgian Blocks, more commonly referred to as cobblestones. From 1885 to the 1900s, the City of Portland used Belgian Blocks as the primary paving surface, bridging the gap between mud roads and asphalt pavement. When asphalt replaced the blocks as the primary road surface, the asphalt was applied directly over the blocks essentially hiding the blocks from the public domain. During street repair projects, the Belgian Blocks are often rediscovered under the asphalt. Per city ordinance, when blocks are exhumed, they are stockpiled for potential future redeployment.

Belgian Block streetscape in Portland, Oregon, 1928.

To better understand how the City of Portland might redeploy the existing Belgian Blocks, we completed a research report on the Belgian Blocks for the Bureau of Planning and Sustainability, and facilitated two listening sessions with the Portland Historic Landmarks Commission to gather perspective. The report provides the Portland Historic Landmarks Commission (PHLC) and the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) with background information and technical data for consideration of how best the city might utilize the redeployment of its Belgian Blocks.

UNDERSTANDING STONE PETROGRAPHY

Background information on stone petrography is necessary to understand durability, chemical composition, and other factors affecting use of stone in the built environment. When it comes to stone found across the Pacific Northwest, when in doubt, guess basalt. The two quarries that the Belgian Blocks of Portland originate from are the St. Helens and Ridgefield quarries, located in the Columbia Plateau Region.

Ridgefield Quarry, 2011.

In 1931, Harold Fisk produced a history and petrography of Oregon basalts, providing microscopic imaging of different basalts. The work that Fisk did resulted in a comprehensive analysis and categorization of basalt types in Oregon, meaning that comparable basalt types and the locations in Oregon can easily be found and used.[i]

NEOLITE AND LEATHERED

An US Geological survey from 1976 compared the Columbia Plateau basalt flows to the Oregon and Washington coastal basalt flows, giving specific chemical composition of the samples taken.[ii] To further identify the Belgian Block’s thru petrographic differences, a report from 1983 tests the characteristics of two different types of stone blocks at Lewis and Clark college. The types are referred to as “Neolite” and “Leathered,” the latter a common name that may have been derived by the supplier of the stone at the time of installation.

Belgian Blocks at Lewis and Clark College. Lyn Topkina, 2014.

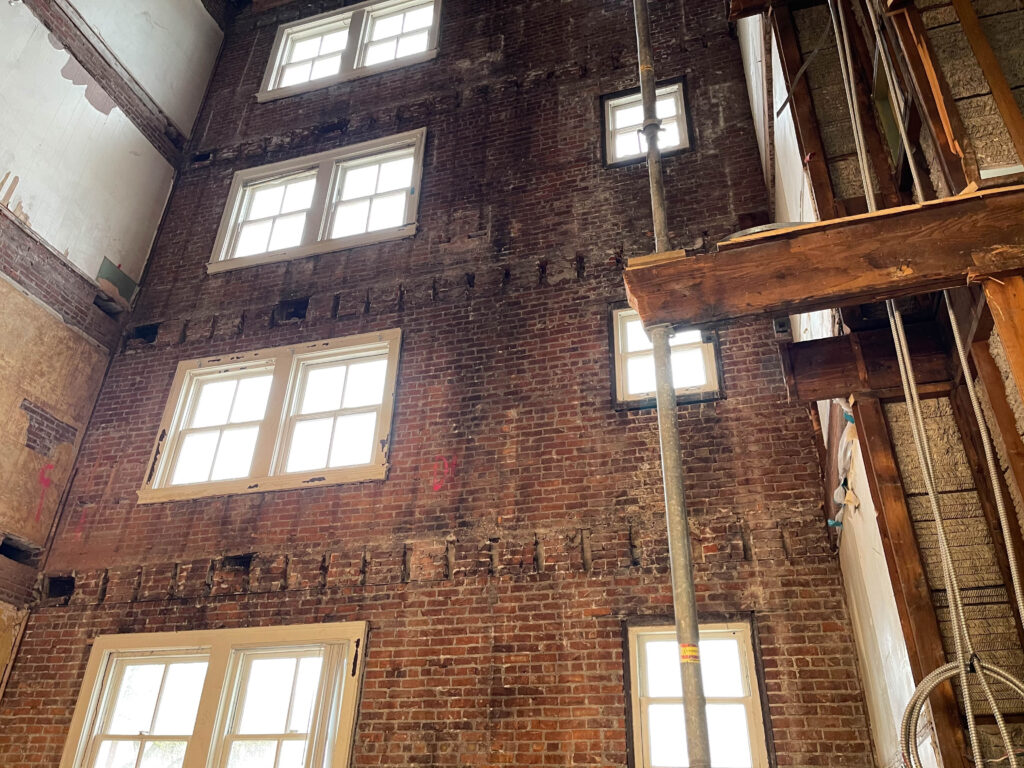

During the 1970s, with renewed interest in saving Portland’s historic character, the City of Portland passed ordinances no. 139670 and no. 141548 in 1975 providing guidance for redeployment of Belgian Blocks removed during street repair projects. At the time of adoption, these ordinances were primarily focused on salvaging characteristics of Portland’s original street scape. As a result, the ordinances did not address the practical aspects of re-deployment and could not anticipate the Americans with Disability Act (ADA) requirements mandating accessibility for all citizens.

Re-deployment of Belgian Blocks within the public right-of-way must meet modern building and land use codes like ADA and historic review. As a part of any re-deployment of Belgian blocks in public spaces, understanding how the blocks meet, or could be modified to meet, current accessibility codes are critical. Specifically related to the use as walking and biking surfaces, two primary concerns arise: tripping and slipping.

Belgian Block, Lyn Topinka, 2014.

Our report demonstrates that it is possible through manipulation of the stone surface, use of setting means and methods, and testing, to modify the Belgian Blocks to allow for reuse as horizontal surfaces. Modifying the physical characteristics of the blocks to meet tripping and slipping standards for re-deployment is possible. Many modification techniques exist for both shop and field modifications. The report focuses on two: cutting and dressing surfaces.

NEXT STEPS

In review of the primary issues raised regarding resistance to redeployment of the Belgian Blocks, the research performed and presented in the Belgian Block Report provide data and ideas by which both the PHLC and PBOT are able to reconsider polices and from which more alignment with similar goals for redeployment may be met. Our recommendations include:

1. The historic ordinances need to be updated to reflect more deployment options;

2. Design details for deployment are in need of updating and reflect various methodologies;

3. Provide objective criteria for linear deployment of Belgian Blocks within the Public Right of Way;

4. Provide clarity that streetcar and light rail stops are to use Belgian Block in linear patterns;

5. Allow modification of the block surfaces to increase slip resistance and promote textural variations.

Read the full: Belgian Block Report

[i] Harold Fisk, “The History and Petrography of the Basalts of Oregon,” Masters of Art and Science Diss. (1931), University of Oregon, Eugene, OR. University of Oregon Library, 461. F57.

[ii] Allan B. Griggs, and Donald A. Swanson, The Columbia River Basalt Group in the Spokane Quadrangle Washington, Idaho, and Montana, with a Section on Petrography, Geological Survey Bulletin 1413, US Geological Survey (1976).