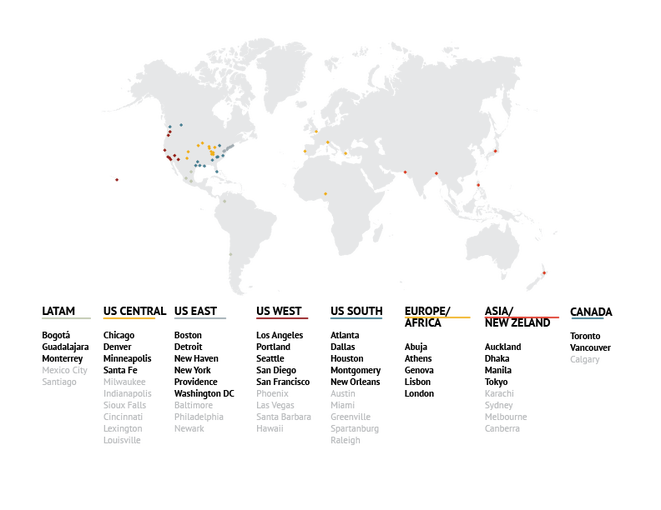

Architecture for Humanity Chapter Network – 30 remaining chapters after the bankruptcy

The answer is there is much to come! If anything it foreshadows a new beginning!

In the wave of the bankruptcy, all intellectual property including the name Architecture for Humanity and slogans like Design Like You Give a Damn, and the website including the Open Source Network have all become property of the bank. I will speak about the organization in past tense because technically it no longer exists. For those who are unfamiliar, Architecture for Humanity’s core mission was “[AFH] believes everyone deserves access to the benefits of good design.” Their publication Design Like You Give a Damn popularized pro bono work and disaster relief design efforts. Architecture for Humanity promoted a unique idea of crowd sharing design ideas for disaster relief through their Open Source Network, which could then be accessed by communities in need. The goal was to provide design solutions to communities in need that couldn’t afford the time and energy required to solve rebuilding design problems. Reconstruction projects after disasters are typically poorly designed and don’t respond to community socio-cultural and economic needs. Architecture for Humanity strove to solve this dilemma through a worldwide network of designers volunteering their time and ideas. Architecture for Humanity had local chapters that addressed local communities’ efforts instead of global disaster relief. Local chapters focused on creating the resiliency within communities.

My involvement in Architecture for Humanity started with the Hurricane Katrina disaster when our Clemson University studio began designing and fabricating a disaster-relief housing prototype in New Orleans. This was added to the Open Architecture Network (OAN) with the hope that the prototype could be a solution to the rebuilding effort. Like most of these projects, efforts were stifled by the bureaucracy of disaster relief. Since then, I have been volunteering for the past four years on small community projects through the AFH Portland Chapter.

Janus Youth’s Village Garden pavilion – Designed and built by AFH PDX Chapter in collaboration with Oregon Tradeswomen

As a result of the AFH filing for bankruptcy, the AFH core headquarters has collapsed leaving the chapter network to reorganize and create a new identity. The intellectual property of AFH, including the name and website and the OAN are all property of the bank. Of the 57 original chapters, 30 chapters are moving forward to continue on AFH’s path. A transitional steering committee has been formed with representatives from every region and will form an advisory board that will set the stage for self-governance and strategic partnerships. It is also interesting that AFH originally never intended to have a chapter network. Those who were inspired by the cause took it upon themselves to create local chapters and AFH agreed to allow these satellite chapters to become part of the organization. As one of the directors of the Portland chapter, I have been participating in re-imagining our mission statement and goals, looking for new opportunities to connect with other non-profits, and reaching outside of architecture to include all design fields. We can also learn from other design non-profits such as Public Architecture and Architects without Borders.

Non-profit design work has received some skepticism of whether a sustainable business model can be reached surrounding the bankruptcy of AFH. AFH’s vision was so powerful, that the non-profit grew exponentially in its original years. For an organization that relied heavily on donations to keep running, the stability was compromised when donations waned and AFH struggled to keep the headquarters office funded. The rapid growth seemed to be a large cause of the sudden deficit. Many contribute the downfall to an unsustainable business model, increased competition for financing, and the founders not being able to adapt their vision to a changing market. The press skeptics raise the question of whether donors will be reluctant to contribute to similar non-profits after the collapse of AFH. Cameron Sinclair, AFH’s founder, responds to this criticism well by saying “I don’t think the idea of architects doing humanitarian work is a failure because AFH ended, I think it will be a failure if architects realize they don’t care.” The committed 30 chapters are determined to carry on with or without support for large donors because they have support of their dedicated volunteers.

AFH Headquarters project – Maeami-hama Community House, 2012 – Community design input for post-disaster rehabilitation

There are many lessons to be learned as the remaining volunteers of AFH move forward to re-envision the organization. The future is still unclear, but the chapter network will learn from headquarters’ shortcomings. The business model will be changed, the organization of the network will no longer rely on a head chapter, and the projects might become more localized and financially sustainable. The bankruptcy has made the network of chapters stronger and our communication with each other has enabled continued enthusiasm for the cause. It is an exciting future for everyone involved because we are all included in the organization’s recreation. The Portland Chapter hopes to explore ways we can best connect communities to design. We want to provide the guidance and knowledge of design language and mediums to enable community visions.

I hope this can be a reminder on how important design and architecture are to creating vibrant communities. Organizations like AFH, Public Architecture, and Architects without Borders are all striving to bring greater accessibility to design. These organizations bring professionals closer to their community, give students and emerging professionals design and management experience, and help communities solve their design needs. The remaining chapters, consisting of thousands of volunteers around the world, are committed to providing pro-bono design services, advocacy, and training within our local communities. The next question to be asked is how can the AEC community be supported in ways that enable more professionals to provide accessible design?

Written by Hali Knight, Architect I

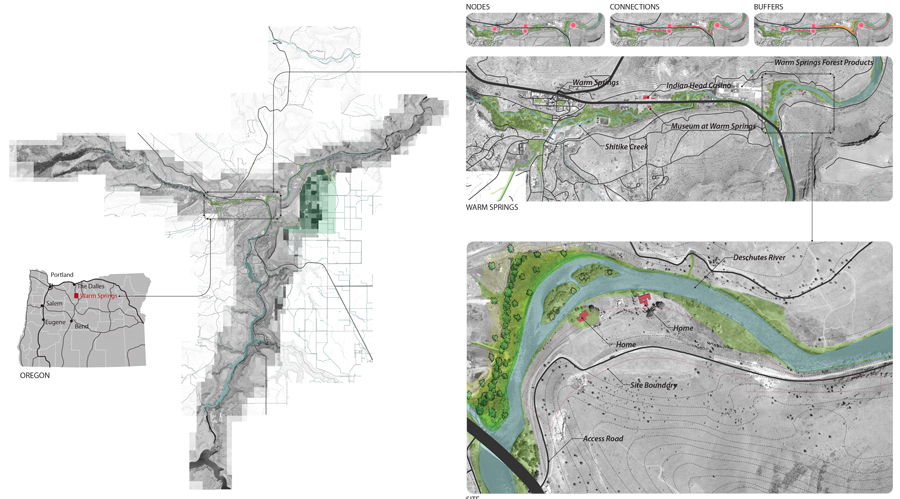

Projects that integrate building science, stewardship planning, and place design are simultaneously exciting and challenging. Any one of the three core concepts can drive the decision making process resulting in a number of solutions. Our current concepts for minimalist eco structures, or “Huts” in the beautiful High Desert of Eastern Oregon are a fantastic challenge.

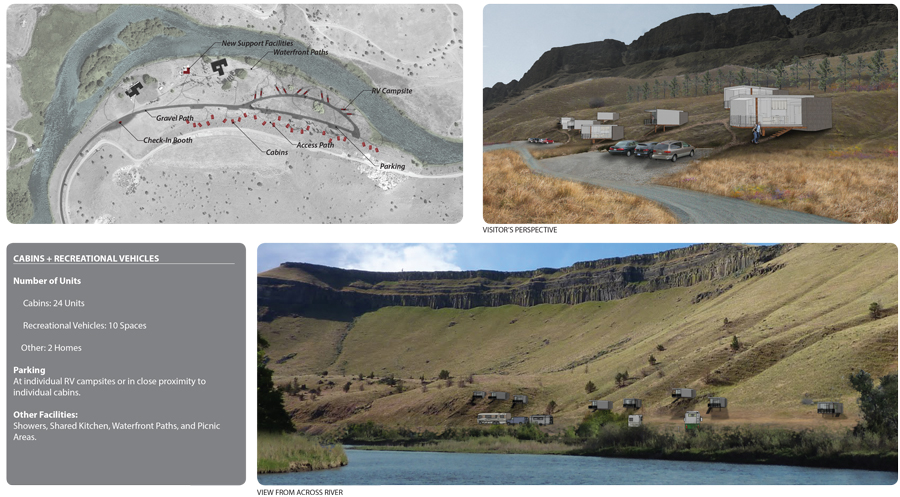

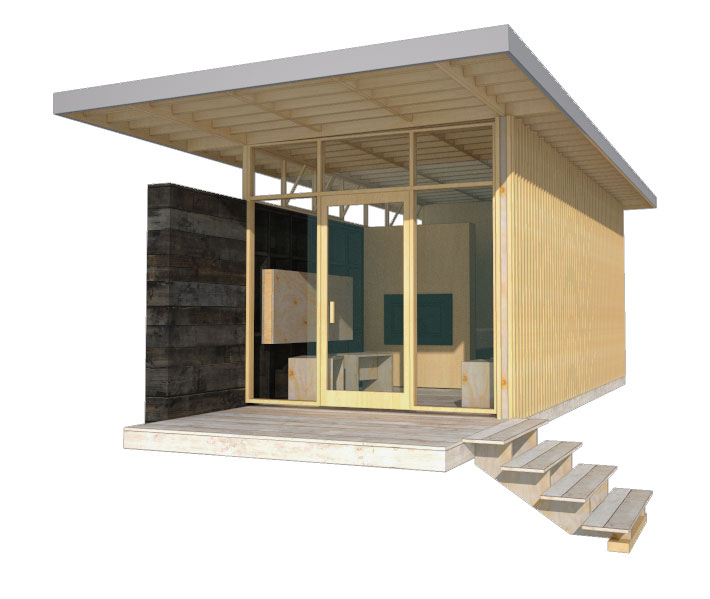

Projects that integrate building science, stewardship planning, and place design are simultaneously exciting and challenging. Any one of the three core concepts can drive the decision making process resulting in a number of solutions. Our current concepts for minimalist eco structures, or “Huts” in the beautiful High Desert of Eastern Oregon are a fantastic challenge. Working with the The Confederate Tribes of Warm Springs, PMA created a prototype model, easily constructed and assembled off site (test fit), then transported to the site and efficiently erected. The prototype was designed to be economical and constructed from lumber from the local lumber mill that produces products from high desert pines. A contemporary design style was chosen to harmonize with existing mid-century Belluschi homes on the property. Both the Belluschi homes and the Eco-Huts stand in contrast with the landscape and topography.

Working with the The Confederate Tribes of Warm Springs, PMA created a prototype model, easily constructed and assembled off site (test fit), then transported to the site and efficiently erected. The prototype was designed to be economical and constructed from lumber from the local lumber mill that produces products from high desert pines. A contemporary design style was chosen to harmonize with existing mid-century Belluschi homes on the property. Both the Belluschi homes and the Eco-Huts stand in contrast with the landscape and topography.

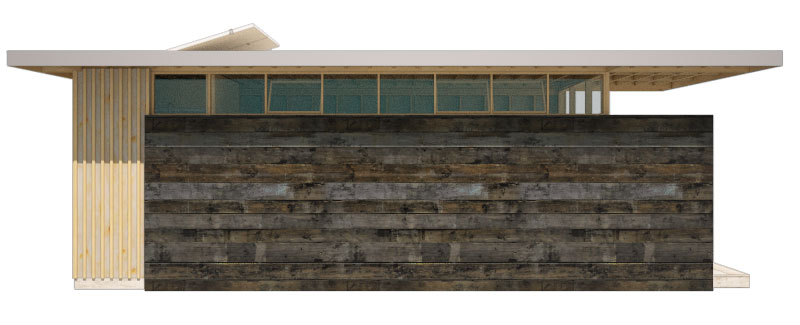

Conceived to have minimal footprints on the land, the Huts rest on piers elevating the floor above the land and accommodating the undulating landscape. A modular dimension was chosen permitting variation in the Eco-Hut sizes. The floor, walls, and roof planes are built off-site and tilted in place. Exterior stained wood material varying from plywood to sawn boards were chosen to harmonize with the High Desert landscape and be of minimal maintenance to the Tribes. Plywood panels are dressed with battens and either in-set from the wood framing or installed flush to the exterior. Sawn mill boards are stained dark desert grey and applied horizontally to create solid side walls atop of which are placed ribbon windows. The primary entry and view wall is a wood frame window and door façade. A deep roof overhang protects the interior from solar gain. Interiors are exposed panel faces or stained mill boards. Partial height walls denote areas of more privacy. The process of assembling the Eco-Huts on-site and disassembling them in the future determined the material pallet of dimensional lumber and pre-assembled wood window walls. The prototype incorporates modular concepts enabling variation in floor plan and amenities in direct response to the Owner’s request for market flexibility.

Conceived to have minimal footprints on the land, the Huts rest on piers elevating the floor above the land and accommodating the undulating landscape. A modular dimension was chosen permitting variation in the Eco-Hut sizes. The floor, walls, and roof planes are built off-site and tilted in place. Exterior stained wood material varying from plywood to sawn boards were chosen to harmonize with the High Desert landscape and be of minimal maintenance to the Tribes. Plywood panels are dressed with battens and either in-set from the wood framing or installed flush to the exterior. Sawn mill boards are stained dark desert grey and applied horizontally to create solid side walls atop of which are placed ribbon windows. The primary entry and view wall is a wood frame window and door façade. A deep roof overhang protects the interior from solar gain. Interiors are exposed panel faces or stained mill boards. Partial height walls denote areas of more privacy. The process of assembling the Eco-Huts on-site and disassembling them in the future determined the material pallet of dimensional lumber and pre-assembled wood window walls. The prototype incorporates modular concepts enabling variation in floor plan and amenities in direct response to the Owner’s request for market flexibility. Inherent in our design approach for the Eco-Huts is the creation of design solutions that emphasize the uniqueness of Place. The concept includes Land Restoration and Land Stewardship. PMA’s goals when designing the prototypes was to help enhance the natural beauty of the river edge by integrating a built structure into the landscape that has minimal disturbance to the site and will leave no footprint when removed. Willows, sedges, and juniper will be planted to provide riparian cover along the Deschutes River in an effort to increase fish habitat and mitigate flooding. The plantings will also help mitigate visual impact from the river. The lumber mill site’s river edge offers an opportunity to create an employee park and river restoration replacing equipment storage and log staging. The Eco-Huts offer an opportunity to test the integration of stewardship planning and place design.

Inherent in our design approach for the Eco-Huts is the creation of design solutions that emphasize the uniqueness of Place. The concept includes Land Restoration and Land Stewardship. PMA’s goals when designing the prototypes was to help enhance the natural beauty of the river edge by integrating a built structure into the landscape that has minimal disturbance to the site and will leave no footprint when removed. Willows, sedges, and juniper will be planted to provide riparian cover along the Deschutes River in an effort to increase fish habitat and mitigate flooding. The plantings will also help mitigate visual impact from the river. The lumber mill site’s river edge offers an opportunity to create an employee park and river restoration replacing equipment storage and log staging. The Eco-Huts offer an opportunity to test the integration of stewardship planning and place design.

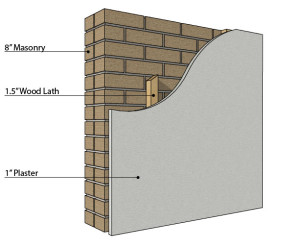

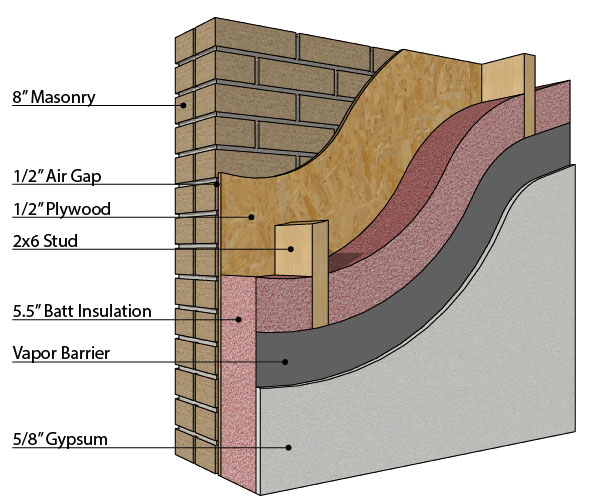

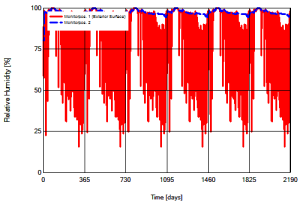

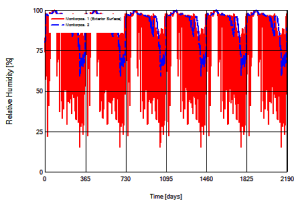

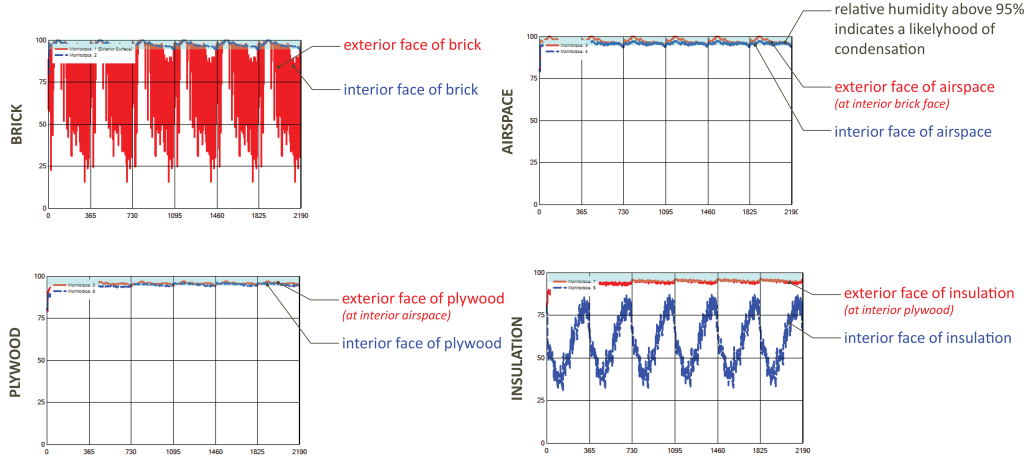

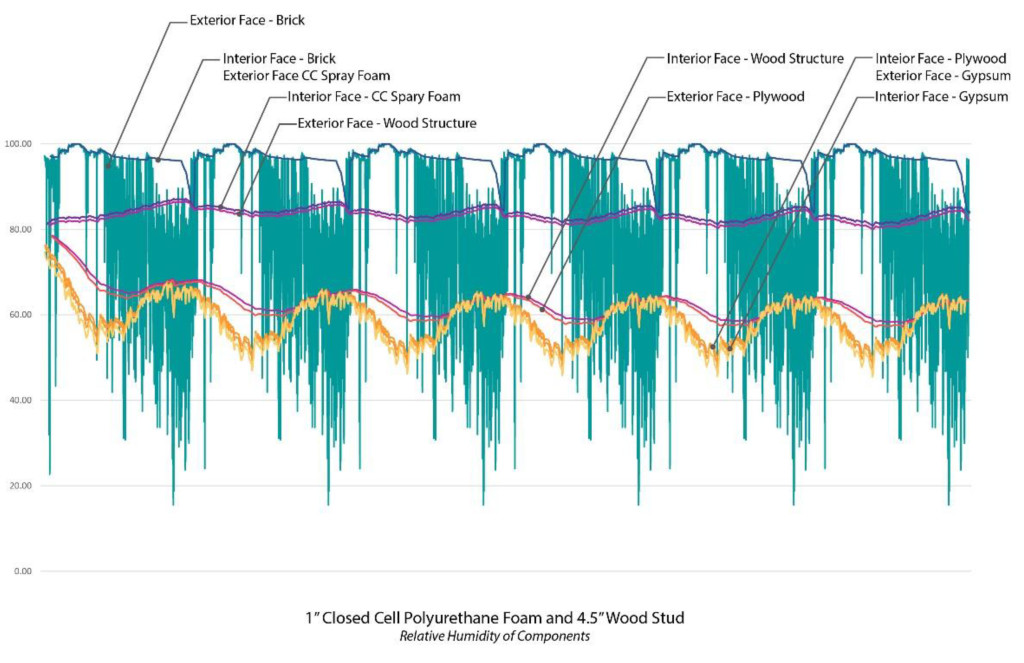

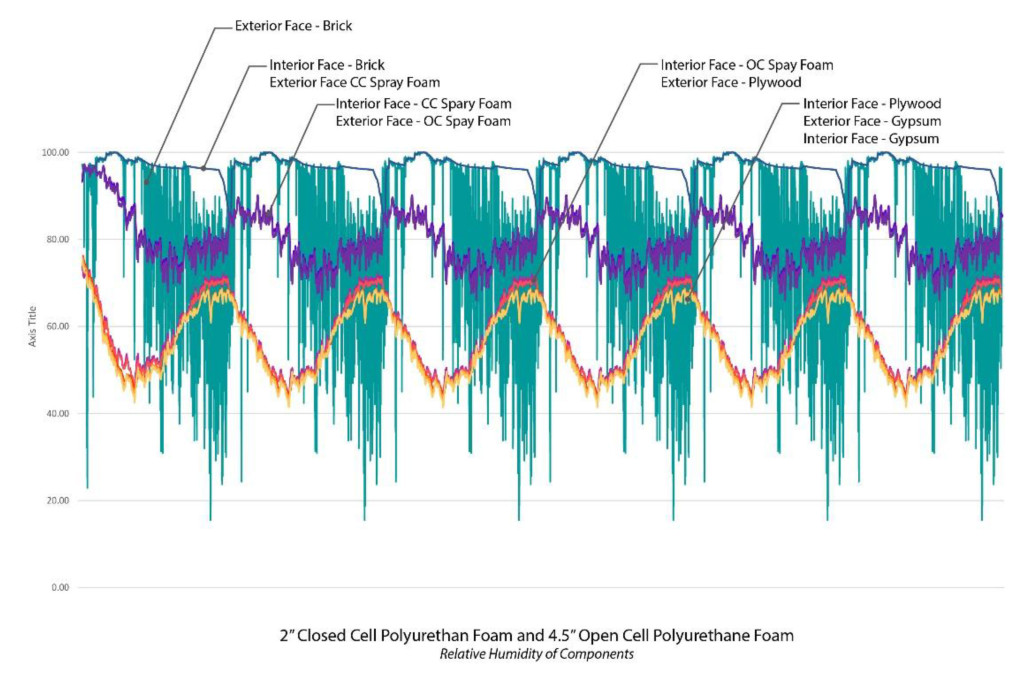

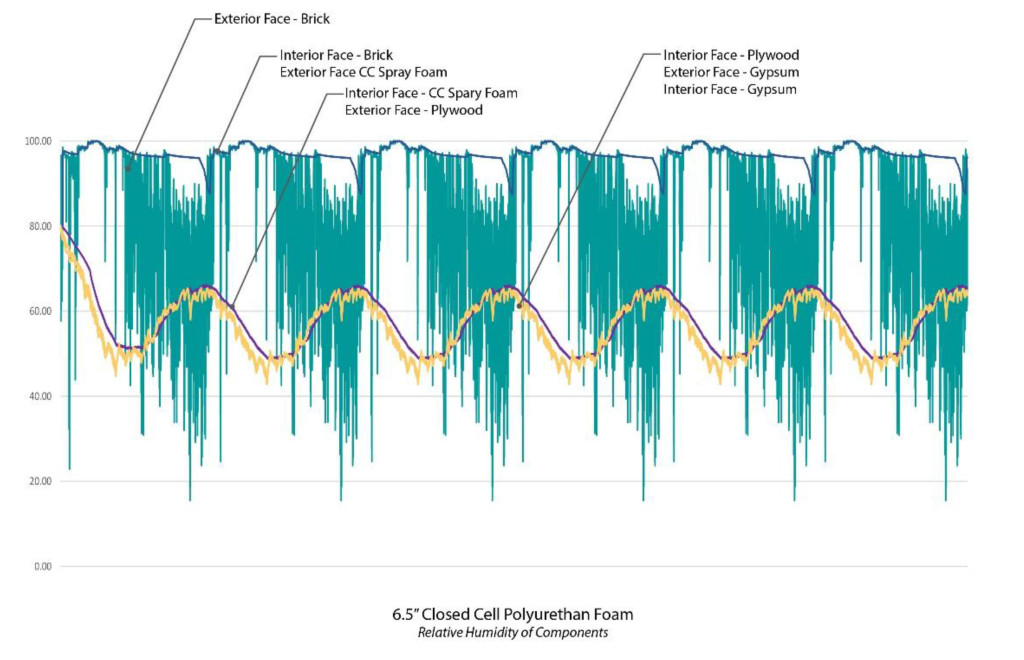

The results of the initial analysis indicated that as might be expected the masonry was not only exposed to longer periods of cool temperatures, it rarely was capable of fully drying. The two charts at the right show the relative humidity in the original construction and the proposed construction where each vertical line marks a calendar year. Note that a relative humidity above 95% indicates a likelihood of condensation. As can be seen in the original construction, during the wet months the relative humidity hovers at about 95%, but drops off significantly during the warmer months. Alternately in the proposed construction the relative humidity rarely drops below 95%, indicating that moisture is present in the masonry almost year round. When the individual layers are examined it becomes clear that in addition to considerable moisture in the masonry itself, water is likely to condense within the wall cavity. As seen in the series of charts below the relative humidity remains high through the airspace and plywood only dropping off between the exterior and interior face of the insulation.

The results of the initial analysis indicated that as might be expected the masonry was not only exposed to longer periods of cool temperatures, it rarely was capable of fully drying. The two charts at the right show the relative humidity in the original construction and the proposed construction where each vertical line marks a calendar year. Note that a relative humidity above 95% indicates a likelihood of condensation. As can be seen in the original construction, during the wet months the relative humidity hovers at about 95%, but drops off significantly during the warmer months. Alternately in the proposed construction the relative humidity rarely drops below 95%, indicating that moisture is present in the masonry almost year round. When the individual layers are examined it becomes clear that in addition to considerable moisture in the masonry itself, water is likely to condense within the wall cavity. As seen in the series of charts below the relative humidity remains high through the airspace and plywood only dropping off between the exterior and interior face of the insulation.  Given these initial results we suggested a redesign of the insulation system. The existing two wythe wall was not capable of adequately protecting the interior of the building, and the redesign had to accommodate for water infiltration through the masonry. Two options were discussed A) treat the masonry as a veneer wall and install waterproofing to the exterior face of the plywood as a drainage plane or B) install insulation that could be exposed to moisture and water. The constructability of Option A was significantly more complex than that of Option B so our initial analysis focused on Option B.

Given these initial results we suggested a redesign of the insulation system. The existing two wythe wall was not capable of adequately protecting the interior of the building, and the redesign had to accommodate for water infiltration through the masonry. Two options were discussed A) treat the masonry as a veneer wall and install waterproofing to the exterior face of the plywood as a drainage plane or B) install insulation that could be exposed to moisture and water. The constructability of Option A was significantly more complex than that of Option B so our initial analysis focused on Option B.

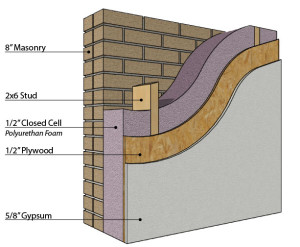

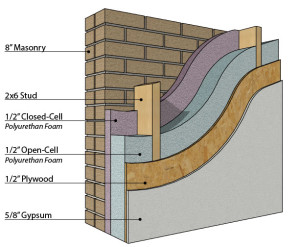

Spray foam was identified as an alternative to the original batt insulation because it can both serve as a vapor retarder and insulate even when exposed to moisture. Two design options were investigated to determine the extent of closed cell foam necessary to adequately protect the interior surfaces from moisture. As can be seen to the right we investigated a construction filled entirely with closed cell polyurethane foam vs. a cavity filled with a combination of closed and open cell polyurethanes. Additionally we looked at the condition of moisture/heat transfer at the perceived weakest point in the structure, where the structural framing was only barely (1/2”) separated from the masonry. The structural integrity of the seismic upgrade depended on a minimal distance between the framing and the existing masonry, but concerns existed as to whether the wood would be exposed to enough moisture to cause mold.

Spray foam was identified as an alternative to the original batt insulation because it can both serve as a vapor retarder and insulate even when exposed to moisture. Two design options were investigated to determine the extent of closed cell foam necessary to adequately protect the interior surfaces from moisture. As can be seen to the right we investigated a construction filled entirely with closed cell polyurethane foam vs. a cavity filled with a combination of closed and open cell polyurethanes. Additionally we looked at the condition of moisture/heat transfer at the perceived weakest point in the structure, where the structural framing was only barely (1/2”) separated from the masonry. The structural integrity of the seismic upgrade depended on a minimal distance between the framing and the existing masonry, but concerns existed as to whether the wood would be exposed to enough moisture to cause mold.

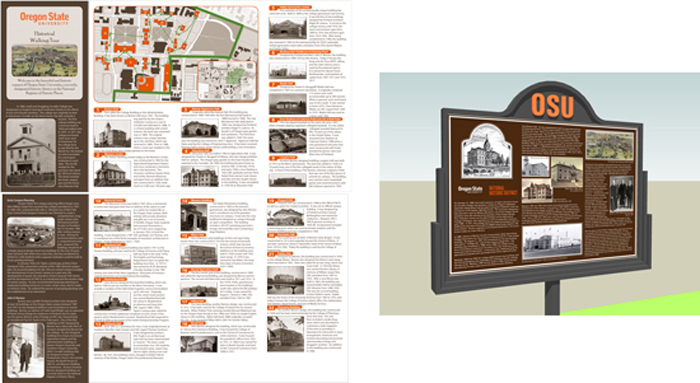

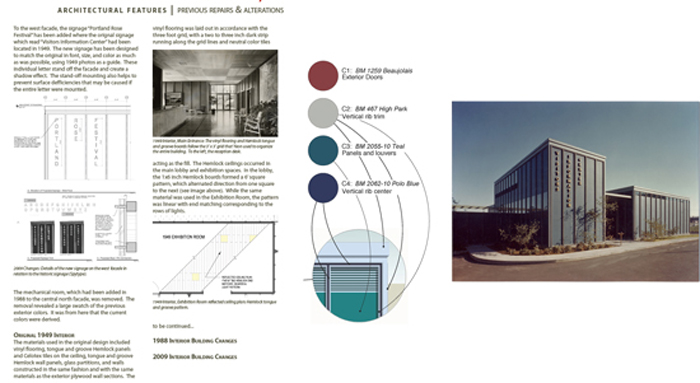

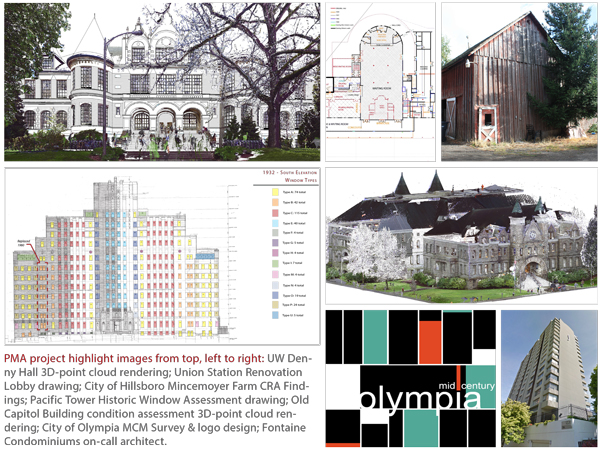

PMA has been involved with several architectural planning projects that center on significant structures from the Mid-Century Modern era. These projects surveyed and documented hundreds of architecturally significant structures that revolutionized architecture and design throughout the 20th century. On the surface such planning projects can be difficult for a wide audience to understand and appreciate because the final project is not a new or renovated building(s). What better opportunity then, for graphic design to communicate and connect the significance of the project and its structures. For these projects, project logos and marketing collateral were designed as the visual symbols that communicate the entire identity of the projects. While both projects surveyed Mid-Century structures one focused on residential structures while the other did not. Both logos use form with text and color to help shape the sense of which type of mid-century modern structures were surveyed.

PMA has been involved with several architectural planning projects that center on significant structures from the Mid-Century Modern era. These projects surveyed and documented hundreds of architecturally significant structures that revolutionized architecture and design throughout the 20th century. On the surface such planning projects can be difficult for a wide audience to understand and appreciate because the final project is not a new or renovated building(s). What better opportunity then, for graphic design to communicate and connect the significance of the project and its structures. For these projects, project logos and marketing collateral were designed as the visual symbols that communicate the entire identity of the projects. While both projects surveyed Mid-Century structures one focused on residential structures while the other did not. Both logos use form with text and color to help shape the sense of which type of mid-century modern structures were surveyed.  Following our planning projects centered on Mid-Century Modern architecture, PMA provided graphic design services for the renovation of the John Yeon designed Rose Festival Headquarters building (former Visitors Information Center). For this project, typography and color were the focal points for communicating the next chapter in this buildings life-cycle. The new graphics, color, and signage produced pay homage to the original design, while being entirely their own.

Following our planning projects centered on Mid-Century Modern architecture, PMA provided graphic design services for the renovation of the John Yeon designed Rose Festival Headquarters building (former Visitors Information Center). For this project, typography and color were the focal points for communicating the next chapter in this buildings life-cycle. The new graphics, color, and signage produced pay homage to the original design, while being entirely their own.

Presently, the City of Portland awarded a contract for Spectator Facilities Construction Project Management Services for a yet unnamed Veterans Memorial Coliseum project. The city is preparing for potential renovation scenarios. The uncertain future of the Coliseum feels like déjà vu.

Presently, the City of Portland awarded a contract for Spectator Facilities Construction Project Management Services for a yet unnamed Veterans Memorial Coliseum project. The city is preparing for potential renovation scenarios. The uncertain future of the Coliseum feels like déjà vu.

Are masonry sealers necessary on historic multi-wythe exterior walls? In general, likely not. Traditional exterior mass unit masonry walls, 3 to 4 wythes thick, leak. But rarely does the amount of water intrusion cause damage to the masonry, the masonry ties, or the interior finishes. Why wouldn’t a sealer be effective for these older walls?

Are masonry sealers necessary on historic multi-wythe exterior walls? In general, likely not. Traditional exterior mass unit masonry walls, 3 to 4 wythes thick, leak. But rarely does the amount of water intrusion cause damage to the masonry, the masonry ties, or the interior finishes. Why wouldn’t a sealer be effective for these older walls?  The porosity and absorption rates of older masonry are often exaggerated because of the brick appearance. Many older masonry units show the results of imperfect firing techniques. It is not unusual to see older masonry with vertical and horizontal cracks due to low firing temperatures or impurities in the original clay mix. The surface cracks may lead to higher rates of absorption around the crack but rarely increase the overall absorption or alter the overall characteristics of the masonry. Masonry sealers will not bridge these firing cracks.

The porosity and absorption rates of older masonry are often exaggerated because of the brick appearance. Many older masonry units show the results of imperfect firing techniques. It is not unusual to see older masonry with vertical and horizontal cracks due to low firing temperatures or impurities in the original clay mix. The surface cracks may lead to higher rates of absorption around the crack but rarely increase the overall absorption or alter the overall characteristics of the masonry. Masonry sealers will not bridge these firing cracks.

To control water intrusion and to increase performance of a masonry wall, it is much more effective to maintain mortar joints through re-pointing process, assure that mortar joints have no voids, replace brick with spalled faces, replace brick that are cracked the full depth, and repair bond line failures. The use of masonry sealers should be based on known research and field tested success and not chosen as a means to remedy poor construction methods.

To control water intrusion and to increase performance of a masonry wall, it is much more effective to maintain mortar joints through re-pointing process, assure that mortar joints have no voids, replace brick with spalled faces, replace brick that are cracked the full depth, and repair bond line failures. The use of masonry sealers should be based on known research and field tested success and not chosen as a means to remedy poor construction methods.

When severe deterioration of masonry walls is not a prevalent condition, what other non-visual processes are employed to determine the cause of deterioration? Two common techniques, well known to historic preservation professionals, are non-destructive testing (NDT) and material testing in the laboratory. NDE methods include RILEM tube water absorption tests, metal detector scanning, video scopes, infra-red photography, ultra sound testing, ground penetrating radar, and in some cases, x-ray diffraction. Common laboratory testing include petrographic examination, electron microscopy, and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) methods.

When severe deterioration of masonry walls is not a prevalent condition, what other non-visual processes are employed to determine the cause of deterioration? Two common techniques, well known to historic preservation professionals, are non-destructive testing (NDT) and material testing in the laboratory. NDE methods include RILEM tube water absorption tests, metal detector scanning, video scopes, infra-red photography, ultra sound testing, ground penetrating radar, and in some cases, x-ray diffraction. Common laboratory testing include petrographic examination, electron microscopy, and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) methods.  FTIR, when combined with the diagnostic RILEM tube field test, in particular is an effective evaluation to determine if masonry sealers have been applied to a wall surface impeding the capillary evaporation of trapped water. RILEM tests also provide an observation of a masonry wall’s initial rate of absorption under wind driven rain circumstances. Petrographic analysis of both masonry and mortars determines the material composition and will identify harmful natural elements and harmful additive elements like salts.

FTIR, when combined with the diagnostic RILEM tube field test, in particular is an effective evaluation to determine if masonry sealers have been applied to a wall surface impeding the capillary evaporation of trapped water. RILEM tests also provide an observation of a masonry wall’s initial rate of absorption under wind driven rain circumstances. Petrographic analysis of both masonry and mortars determines the material composition and will identify harmful natural elements and harmful additive elements like salts. A common misconception in the northwest is that surface spalls are a result of freeze thaw cycles. Freeze thaw susceptibility can only be determined through laboratory testing. Visual observations are insufficient to conclude masonry spalls resulted from freeze thaw forces. Since freeze thaw tests are graded either pass or fail, further tests methods are typically required for additional diagnostic evaluation. More likely sources of surface spalls are hard Portland cement mortars which exceed the strength of the masonry, salts introduced into the masonry through incorrect material selection, or surface sealers impeding the evaporation of water and thus creating a saturated sub surface layer which will freeze. (It is important to distinguish that the masonry unit may not be susceptible to freeze thaw but rather the sealer creates a dam like effect inducing a layer of water subject to freezing)

A common misconception in the northwest is that surface spalls are a result of freeze thaw cycles. Freeze thaw susceptibility can only be determined through laboratory testing. Visual observations are insufficient to conclude masonry spalls resulted from freeze thaw forces. Since freeze thaw tests are graded either pass or fail, further tests methods are typically required for additional diagnostic evaluation. More likely sources of surface spalls are hard Portland cement mortars which exceed the strength of the masonry, salts introduced into the masonry through incorrect material selection, or surface sealers impeding the evaporation of water and thus creating a saturated sub surface layer which will freeze. (It is important to distinguish that the masonry unit may not be susceptible to freeze thaw but rather the sealer creates a dam like effect inducing a layer of water subject to freezing) By combining visual observations with NDE and lab testing, most surface masonry deterioration can be determined and thereby implement proper repair, maintenance, and protection methods.

By combining visual observations with NDE and lab testing, most surface masonry deterioration can be determined and thereby implement proper repair, maintenance, and protection methods.