The second-half of the nineteenth-century was a prosperous time for architectural development in Oregon. This period saw the establishment of professional architects in Oregon, allowing the state to be comparable with eastern architectural development of the same era in the United States. Portland was the center of economic growth and abundance in Oregon, and the U.S. Custom House was built to promote and accommodate Portland’s economic prosperity. Originally U.S. Customs Services was housed in one of Oregon’s earliest public buildings, the Pioneer Courthouse, which was constructed in stages between 1869 and 1903. However, the U.S. Customs Services quickly outgrew this building, and by 1898 construction began on the present U.S. Custom House. (Ross, Marion D., “Architecture in Oregon, 1845-1895,” Oregon Historical Quarterly 57 (1956) 32-64.)

The present U.S. Custom House is a testament to the Italian Renaissance Revival style, popular in the late nineteenth-century architectural vernacular of Oregon. The building was designed in the office of James Knox Taylor, Supervising Architect of the U.S. Treasury Department, and supervised under noted Portland architect Edgar Lazarus. Portland’s U.S. Custom House is a symmetrical four-story building, H-shaped in plan, and encompasses a full city block. Joint efforts by Taylor and Lazarus resulted in a fusion of style that references Renaissance, Mannerist, and Baroque features that are showcased on the exterior and interior of the building. (GSA. U.S. General Services Administration, U.S. Custom House, Portland, OR (Accessed March 12, 2012).)

This fusion of style begins on the first-story walls which are composed of brick masonry enclosed in light-gray granite, with window and door openings that feature semicircular arches. The first and second floors are separated by a balustrade and a granite stringcourse carved with Vitruvian scroll details. The two upper stories are composed of Roman brick and use terra-cotta to display dentil cornice molding and scrolled consoles detailing. The most distinctive Italian Renaissance Revival style is found in the architectural ornamentation of the exterior fenestration, and is most prominently featured around the second and third-story windows. (GSA. U.S. General Services Administration, U.S. Custom House, Portland, OR (Accessed March 12, 2012).)

Allegorical Symbols

The architectural ornamentation or “Gibbs-surround” of the second and third story windows of Portland’s Custom House borrow directly from Italian Palazzos and include several allegorical symbols: a key and a balance, a symbol of the God of Mercury, a hand with two extended fingers, a laurel wreath, a palm branch, and a flaming torch. At the time of completion the Oregonian ran an article that focused on the obscure nature of these allegorical symbols. Lazarus was questioned on the purpose of the symbols, and he commented on how the allegorical symbols held no significance except for their use as decorations. In agreement with the author of the 1901 article in The Morning Oregonian, “Merely Allegorical and Without Special Significance,” it does not follow that a building in the Italian Renaissance Revival style would showcase allegorical symbols solely for their ornamentation. Allegorical ornamentation is purposeful, with every symbol representing to the public a function or aspect of the intended purposes of the building on which they are represented. (“Custom-House Symbols. Merely Allegorical and Without Special Significance,” The Morning Oregonian, Aug 5, 1901, 5. NewsBank and/or the American Antiquarian Society. 2004.)

The balance is the most recognizable symbol, symbolizing justice. It follows that since the U.S. Custom House was built for the U.S. Custom Services, which played a significant role in the economic growth of the area, architectural ornamentation of the symbol of justice would be included. This symbol tells the audience that all services by its governing body will be conducted justly. The key is borrowed from a Christian symbol which references the bureaucratic nature of Saint Peter’s ability to grant or withhold salvation. This symbol was common in architectural ornamentation in the sixteenth-century, when politics and religion were heavily and most complicatedly intertwined. Perhaps the keys are meant to remind those within to repent, but more likely serve as an emblem of time and removers of obstacles- which are also emblems of the Roman God Janis.

The balance is the most recognizable symbol, symbolizing justice. It follows that since the U.S. Custom House was built for the U.S. Custom Services, which played a significant role in the economic growth of the area, architectural ornamentation of the symbol of justice would be included. This symbol tells the audience that all services by its governing body will be conducted justly. The key is borrowed from a Christian symbol which references the bureaucratic nature of Saint Peter’s ability to grant or withhold salvation. This symbol was common in architectural ornamentation in the sixteenth-century, when politics and religion were heavily and most complicatedly intertwined. Perhaps the keys are meant to remind those within to repent, but more likely serve as an emblem of time and removers of obstacles- which are also emblems of the Roman God Janis.

Two other classical symbols are those of the God of Mercury and the flaming torch. The God of Mercury is represented by a staff with serpents entwined. While the symbol of the God of Mercury is often noted as a representation of speed, it is also a representation of opportunity and commerce, which is fitting for its inclusion among the architectural ornamentation of the building. The flaming torch is often related to the God of Eros, who is commonly depicted with bow and arrow and a flaming torch. However, the flaming torch represented on the U.S. Custom House building is more likely an emblem of both enlightenment and hope, similar to the function of the flaming torch in the hand of Lady Liberty. The final two symbols are the palm branch and the laurel wreath, both of which represent victory and glory.

Portland’s U.S. Custom House is unquestionably one of Portland’s finest historic structures. It is an exquisite display of the Italian Renaissance Revival style of architecture with a symmetrical organization, use of terra-cotta, Roman brick, and granite materials, classically engaged Doric, Iconic, and Corinthian Columns, and displays of richly detailed architectural ornamentation found throughout the Gibbs-Surround. While it has been said the allegorical symbolic ornamentation used on U.S. Custom House is without significance and merely decorative, the explanation of each symbol has led to the credible reason for the inclusion of all these symbols. For the architecture of Portland’s U.S. Custom House is in the Italian Renaissance style, a style that uses symbolic ornamentation to signify both emotion and reason.

Portland’s U.S. Custom House is unquestionably one of Portland’s finest historic structures. It is an exquisite display of the Italian Renaissance Revival style of architecture with a symmetrical organization, use of terra-cotta, Roman brick, and granite materials, classically engaged Doric, Iconic, and Corinthian Columns, and displays of richly detailed architectural ornamentation found throughout the Gibbs-Surround. While it has been said the allegorical symbolic ornamentation used on U.S. Custom House is without significance and merely decorative, the explanation of each symbol has led to the credible reason for the inclusion of all these symbols. For the architecture of Portland’s U.S. Custom House is in the Italian Renaissance style, a style that uses symbolic ornamentation to signify both emotion and reason.

Written by Kate Kearney, Marketing Coordinator

There is still much work to be done. The Pittock Mansion Society has identified the top priority projects ranging from the practical structural and electrical work to additional programming and preservation projects. The Centennial celebration will be a grand formal affair, fitting for such a magnificent and unique cultural icon within the City of Portland’s stewardship.

There is still much work to be done. The Pittock Mansion Society has identified the top priority projects ranging from the practical structural and electrical work to additional programming and preservation projects. The Centennial celebration will be a grand formal affair, fitting for such a magnificent and unique cultural icon within the City of Portland’s stewardship.

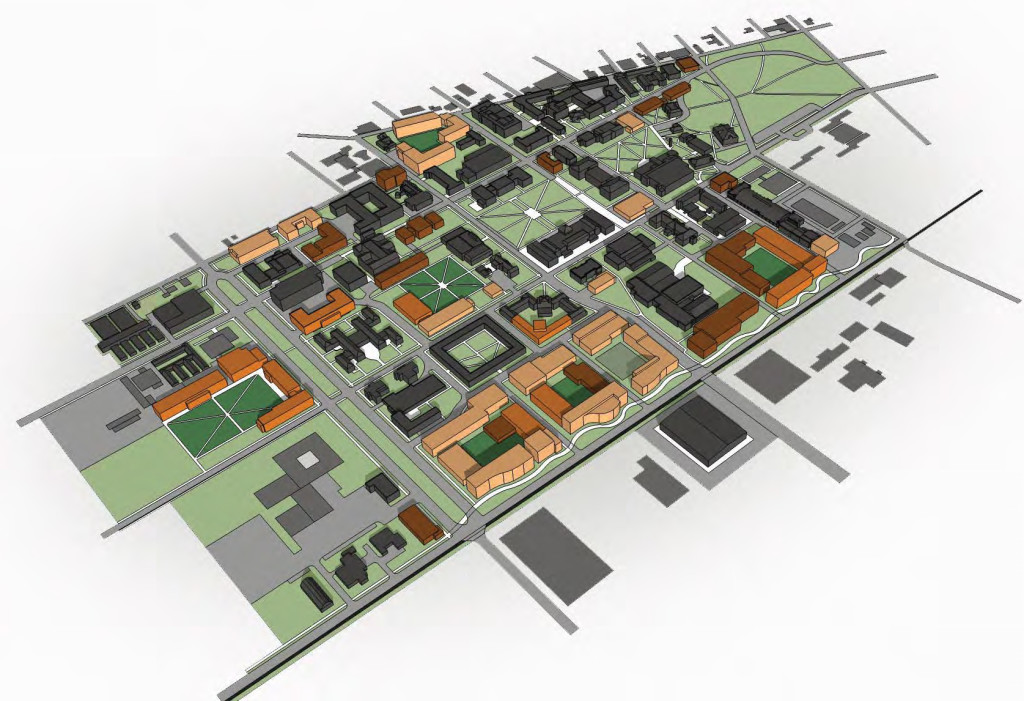

For more information about this exciting project, including a list of buildings for intensive research, mid-century modern properties, city map with property locations, and property descriptions. Visit:

For more information about this exciting project, including a list of buildings for intensive research, mid-century modern properties, city map with property locations, and property descriptions. Visit:

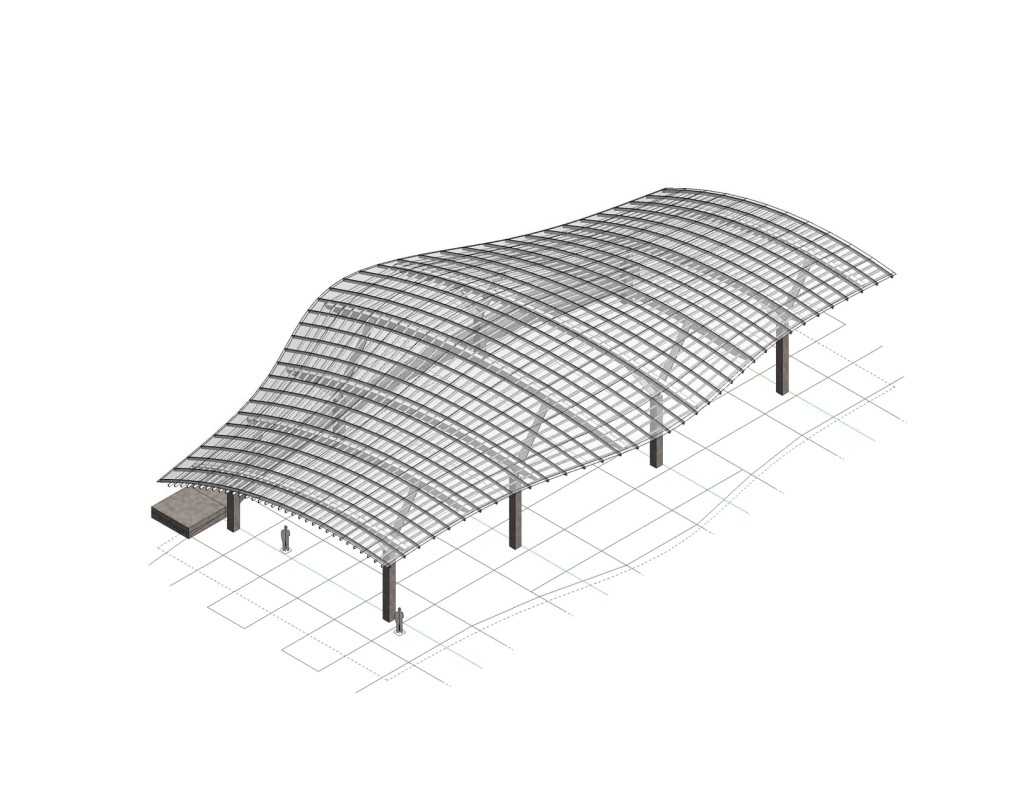

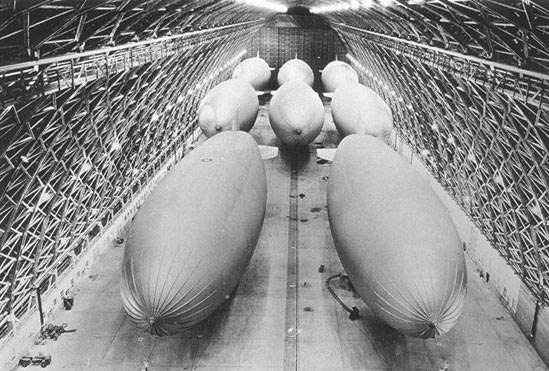

Creative, multi-jurisdictional, community involvement, private / public partnerships, government programs, and national and international marketing campaigns have become key elements to long range cultural resource management plans. The unique structures require innovative solutions matching the monumental character and commanding presence. Success stories abound from the saving of West Baden Springs Hotel in French Lick, Indiana to Centennial Hall in Wroclaw, Poland. The efforts to retain the giant structures are well deserved, because the continued loss of such buildings diminishes our understanding of world events.

Creative, multi-jurisdictional, community involvement, private / public partnerships, government programs, and national and international marketing campaigns have become key elements to long range cultural resource management plans. The unique structures require innovative solutions matching the monumental character and commanding presence. Success stories abound from the saving of West Baden Springs Hotel in French Lick, Indiana to Centennial Hall in Wroclaw, Poland. The efforts to retain the giant structures are well deserved, because the continued loss of such buildings diminishes our understanding of world events.

The balance is the most recognizable symbol, symbolizing justice. It follows that since the U.S. Custom House was built for the U.S. Custom Services, which played a significant role in the economic growth of the area, architectural ornamentation of the symbol of justice would be included. This symbol tells the audience that all services by its governing body will be conducted justly. The key is borrowed from a Christian symbol which references the bureaucratic nature of Saint Peter’s ability to grant or withhold salvation. This symbol was common in architectural ornamentation in the sixteenth-century, when politics and religion were heavily and most complicatedly intertwined. Perhaps the keys are meant to remind those within to repent, but more likely serve as an emblem of time and removers of obstacles- which are also emblems of the Roman God Janis.

The balance is the most recognizable symbol, symbolizing justice. It follows that since the U.S. Custom House was built for the U.S. Custom Services, which played a significant role in the economic growth of the area, architectural ornamentation of the symbol of justice would be included. This symbol tells the audience that all services by its governing body will be conducted justly. The key is borrowed from a Christian symbol which references the bureaucratic nature of Saint Peter’s ability to grant or withhold salvation. This symbol was common in architectural ornamentation in the sixteenth-century, when politics and religion were heavily and most complicatedly intertwined. Perhaps the keys are meant to remind those within to repent, but more likely serve as an emblem of time and removers of obstacles- which are also emblems of the Roman God Janis.  Portland’s U.S. Custom House is unquestionably one of Portland’s finest historic structures. It is an exquisite display of the Italian Renaissance Revival style of architecture with a symmetrical organization, use of terra-cotta, Roman brick, and granite materials, classically engaged Doric, Iconic, and Corinthian Columns, and displays of richly detailed architectural ornamentation found throughout the Gibbs-Surround. While it has been said the allegorical symbolic ornamentation used on U.S. Custom House is without significance and merely decorative, the explanation of each symbol has led to the credible reason for the inclusion of all these symbols. For the architecture of Portland’s U.S. Custom House is in the Italian Renaissance style, a style that uses symbolic ornamentation to signify both emotion and reason.

Portland’s U.S. Custom House is unquestionably one of Portland’s finest historic structures. It is an exquisite display of the Italian Renaissance Revival style of architecture with a symmetrical organization, use of terra-cotta, Roman brick, and granite materials, classically engaged Doric, Iconic, and Corinthian Columns, and displays of richly detailed architectural ornamentation found throughout the Gibbs-Surround. While it has been said the allegorical symbolic ornamentation used on U.S. Custom House is without significance and merely decorative, the explanation of each symbol has led to the credible reason for the inclusion of all these symbols. For the architecture of Portland’s U.S. Custom House is in the Italian Renaissance style, a style that uses symbolic ornamentation to signify both emotion and reason. Many of Portland’s iconic landmark buildings are modern era resources, such as the Veterans Memorial Coliseum, Lloyd Center Mall, U.S. Bancorp tower, and the Portland Building. The survey intentionally excludes these well-known properties in order to highlight broader architectural patterns and identify some of the less prominent buildings that may be considered historically significant in the future.

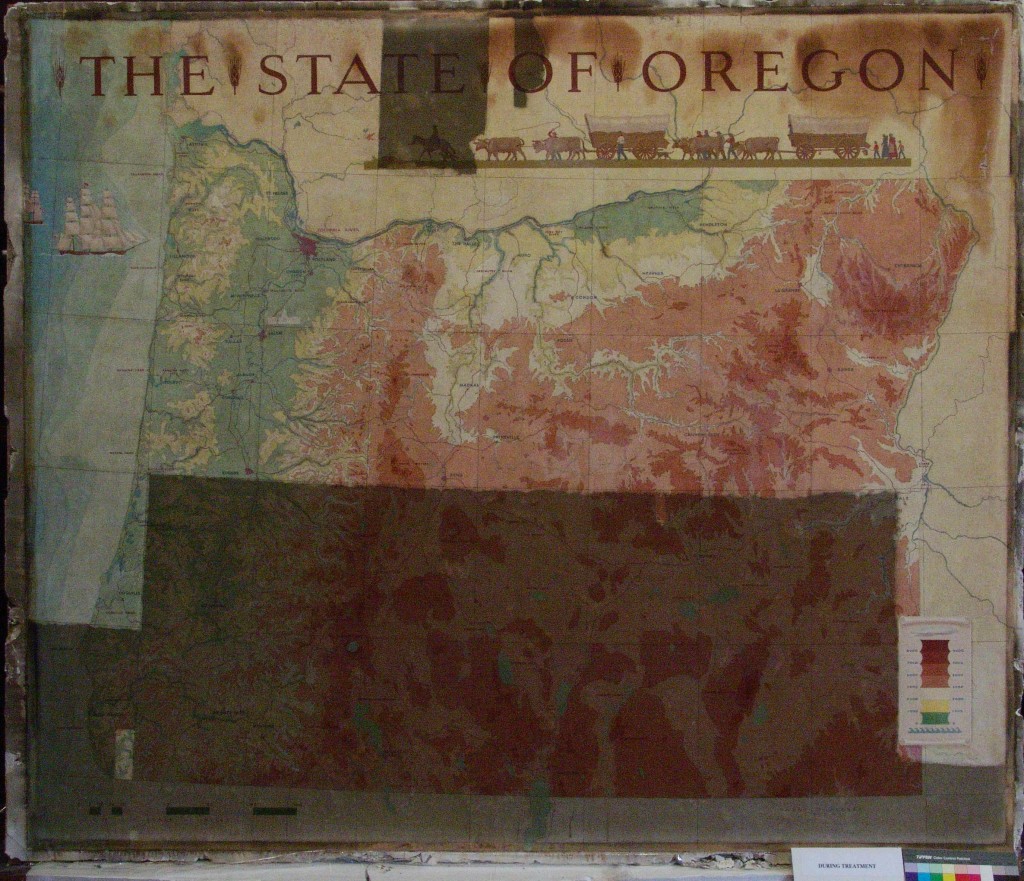

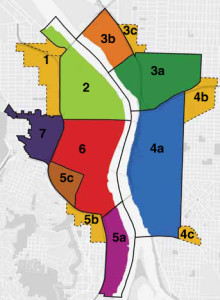

Many of Portland’s iconic landmark buildings are modern era resources, such as the Veterans Memorial Coliseum, Lloyd Center Mall, U.S. Bancorp tower, and the Portland Building. The survey intentionally excludes these well-known properties in order to highlight broader architectural patterns and identify some of the less prominent buildings that may be considered historically significant in the future. Of approximately 976 modern period resources within the Central City’s seven geographic clusters, PMA selected 152 properties for reconnaissance level survey. Representation of geographic clusters, resource typologies, and potential eligibility were considered when selecting properties to survey. In a selective survey, most properties should be considered potentially eligible for historic designation. Online maps, tax assessor information, and Google Earth were used to inform the selection process. Fieldwork involved taking photographs of each property, recording the resource type, cladding materials, style, height, plan type, and auxiliary resources, and then making a preliminary determination of National Register eligibility based on age, integrity, and historic character-defining features. A final report outlines the project and findings, and survey data was added to the Oregon Historic Sites database.

Of approximately 976 modern period resources within the Central City’s seven geographic clusters, PMA selected 152 properties for reconnaissance level survey. Representation of geographic clusters, resource typologies, and potential eligibility were considered when selecting properties to survey. In a selective survey, most properties should be considered potentially eligible for historic designation. Online maps, tax assessor information, and Google Earth were used to inform the selection process. Fieldwork involved taking photographs of each property, recording the resource type, cladding materials, style, height, plan type, and auxiliary resources, and then making a preliminary determination of National Register eligibility based on age, integrity, and historic character-defining features. A final report outlines the project and findings, and survey data was added to the Oregon Historic Sites database.

The Portland Building itself is significant as one of a handful of high-profile building designs that defined the aesthetic of Post Modern Classicism in the United States between the mid-1960s and the 1980s. Constructed in 1982, the Portland Public Service Building is nationally significant as the notable work that crystallized Michael Graves’s reputation as a master architect and as an early and seminal work of Post-Modern Classicism, an American style that Graves himself defined through his work. The structure is ground-breaking for its rejection of “universal” Modernist principles in favor of bold and symbolic color, well-defined volumes, and stylized- and reinterpreted-classical elements such as pilasters, garlands, and keystones.

The Portland Building itself is significant as one of a handful of high-profile building designs that defined the aesthetic of Post Modern Classicism in the United States between the mid-1960s and the 1980s. Constructed in 1982, the Portland Public Service Building is nationally significant as the notable work that crystallized Michael Graves’s reputation as a master architect and as an early and seminal work of Post-Modern Classicism, an American style that Graves himself defined through his work. The structure is ground-breaking for its rejection of “universal” Modernist principles in favor of bold and symbolic color, well-defined volumes, and stylized- and reinterpreted-classical elements such as pilasters, garlands, and keystones.  As one of the earliest large-scale Post-Modern buildings constructed, Graves’s design for the Portland Building was daring; almost shocking, in its vision for the future, and for its proposition as to what “after Modernism” could mean for architecture. The building itself is a fifteen-story regularly-fenestrated symmetrical monumental block clad in scored off-white colored stucco and set on a stepped two-story pedestal of blue-green tile. The building’s style is expressed through paint and applied ornament that implies classical architectural details, including terracotta tile pilasters and keystone, mirrored glass, and flattened and stylized garlands, among other elements that are intended to convey multiple meanings. For instance, the building is organized in a classical three-part division, bottom, middle, and top in reference to the human body, foot, middle, and head. At the same time, the building’s colors represent parts of the environment, with blue-green tile at the base symbolizing the earth and the light blue at the upper-most story representing the sky. The building uses layers of references to physically and symbolically tie it to place, its use, and the Western architectural tradition.

As one of the earliest large-scale Post-Modern buildings constructed, Graves’s design for the Portland Building was daring; almost shocking, in its vision for the future, and for its proposition as to what “after Modernism” could mean for architecture. The building itself is a fifteen-story regularly-fenestrated symmetrical monumental block clad in scored off-white colored stucco and set on a stepped two-story pedestal of blue-green tile. The building’s style is expressed through paint and applied ornament that implies classical architectural details, including terracotta tile pilasters and keystone, mirrored glass, and flattened and stylized garlands, among other elements that are intended to convey multiple meanings. For instance, the building is organized in a classical three-part division, bottom, middle, and top in reference to the human body, foot, middle, and head. At the same time, the building’s colors represent parts of the environment, with blue-green tile at the base symbolizing the earth and the light blue at the upper-most story representing the sky. The building uses layers of references to physically and symbolically tie it to place, its use, and the Western architectural tradition. The boxy, fifteen-story building is located in the center of downtown Portland, Oregon, occupying a full 200 by 200-foot city block right next to City Hall. The Portland Building is a surprising jolt of color within the more restrained environment and designs of nearby buildings, with its blue tile base and off-white stucco exterior accented with mirrored glass, earth-toned terracotta tile, and sky-blue penthouse. The figure of Lady Commerce from the city seal, reinterpreted by sculptor Ray Kaskey to represent a broader cultural tradition and renamed ‘Portlandia,’ is placed in front of one of the large windows as a further reference to the city. The building is notable for its regular geometry and fenestration as well as the architect’s use of over-scaled and highly-stylized classical decorative features on the building’s facades, including a copper statue mounted above the entry, garlands on the north and south facades, and the giant pilasters and keystone elements on the east and west facades. Whether or not one judges the building to be beautiful or even to have fulfilled Graves’s ideas about being humanist in nature, it is undeniably important in the history of American architecture. The building has been dispassionately evaluated in various scholarly works about the history of architecture and is inextricably linked to the rise of the Post-Modern movement.

The boxy, fifteen-story building is located in the center of downtown Portland, Oregon, occupying a full 200 by 200-foot city block right next to City Hall. The Portland Building is a surprising jolt of color within the more restrained environment and designs of nearby buildings, with its blue tile base and off-white stucco exterior accented with mirrored glass, earth-toned terracotta tile, and sky-blue penthouse. The figure of Lady Commerce from the city seal, reinterpreted by sculptor Ray Kaskey to represent a broader cultural tradition and renamed ‘Portlandia,’ is placed in front of one of the large windows as a further reference to the city. The building is notable for its regular geometry and fenestration as well as the architect’s use of over-scaled and highly-stylized classical decorative features on the building’s facades, including a copper statue mounted above the entry, garlands on the north and south facades, and the giant pilasters and keystone elements on the east and west facades. Whether or not one judges the building to be beautiful or even to have fulfilled Graves’s ideas about being humanist in nature, it is undeniably important in the history of American architecture. The building has been dispassionately evaluated in various scholarly works about the history of architecture and is inextricably linked to the rise of the Post-Modern movement.