With a firm comprised of architects and planners, we understand and assist owners and developers navigate local historic preservation incentives made available by the City of Portland. The following is a comprehensive overview of incentives offered by the City, as of 2016, in the form of various use allowances, development rules “waivers,” and opportunities to transfer allowed but unused floor area to other property owners, creating an opportunity for a monetary benefit. We grouped the available historic preservation incentives available by the following: City of Portland Incentives, City of Portland/State of Oregon Building Code Allowances, and Portland Development Commission Programs.

The City of Portland’s Central City 2035 Plan (as well as other related City code projects) are currently under review. The Proposed Draft was published in June 2016 and is being reviewed by many City and non-City agencies, bureaus, and organizations. Proposed changes directly affect portions of the Portland Zoning Code, but the existing Zoning Code will remain in effect until adoption of the final Central City 2035 Plan, probably in late 2018. Increased transfer options are the major change proposed.

“Landmark” as defined by the City is a property individually listed on the National Register, or evaluated by the City of Portland as a local historic resource. Many incentives are also available to resources designated contributing to a National Register-listed Historic District or locally designated Conservation District.

Marshall Wells Lofts building preservation plan.

CITY OF PORTLAND INCENTIVES

Additional density in Single-Dwelling zones. Landmarks in Single-Dwelling zones may be used as multi-dwelling structures, up to a maximum of one dwelling unit for each 1,000 square feet of site area. No additional off-street parking is required, but the existing number of off-street parking spaces must be retained. The landmark may be expanded and the new floor area used for additional dwelling units only if the expansion is approved through historic design review.

Additional density in Multi-Dwelling zones. Landmarks and contributing structures in historic districts located in multi-dwelling zones may be used as multi-dwelling structures, with no maximum density. No additional off-street parking is required, but the existing number of off-street parking spaces must be retained. The building may be expanded and the new floor area used for additional dwelling units only if the expansion is approved through historic design review.

Nonresidential uses in the RX zone. In the RX zone, except on certain sites which directly front on the Park Blocks, up to 100 percent of the floor area of a landmark or contributing structure may be approved for Retail Sales and Service, Office, Major Event Entertainment, or Manufacturing and Production uses through Historic Preservation Incentive Review.

Nonresidential uses in the RH, R1 and R2 zones. In the RH, R1 and R2 zones, up to 100 percent of the floor area of a landmark or contributing structure may be approved for Retail Sales and Service, Office, or Manufacturing and Production uses as follows:

Daycare is an allowed use in all residential zones in historic landmark or contributing structures. In non-historic structures, daycare uses in residential zones other than RX require a conditional use review.

Conditional uses in Residential, Commercial, and Employment zones. In these zones, applications for conditional uses at landmarks or contributing structures are processed through a Type II procedure, rather than the longer Type III procedure requiring a public hearing.

Exemption from minimum density. Minimum housing density regulations do not apply in landmarks or contributing structures.

Crane building historic consulting for storefront updates.

Commercial allowances in Central City Industrial zones. National Register-listed properties or those contributing to a National Register-listed historic district have potential to include office and retail uses.

Commercial allowances in employment and industrial zones. Office and retail uses are allowed in landmarks in areas where those uses are otherwise restricted.

Increased maximum parking ratios in Central City. National Register-listed properties or those contributing to a National Register-listed historic district within the Central City Core parking area are allowed to increase parking ratios.

Commercial allowances in Guild’s Lake Industrial Sanctuary District. Increases allowances for office and retail uses in landmarks in an area where non-industrial uses are otherwise restricted.

The transfer of density and floor area ratio (FAR) from a landmark to another location is allowed in Multi-Dwelling, Commercial, and Employment zones. Historic properties with unused development “potential” therefore may find a market for the FAR.

Proposed Development transfer opportunities (potentially adopted in 2018):

Landmarks and contributing resources in historic districts will be able to transfer FAR City-wide, as long as the “sending” resource meets seismic reinforcement standards. Seismic work may be allowable in phases over a period of years. FAR to be transferred is not only the base amount unused by the existing historic structure, but also an additional 3:1.

U.S. Custom House renovation and historic tax credits.

PORTLAND DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION PROGRAMS

The Portland Development Commission (PDC) has operated several programs to benefit owners of existing buildings (not necessarily historic buildings). These programs have been suspended and will be replaced by the Prosperity Investment Program (PIP). Information about the PIP is not yet available, but the program may still provide benefits to owners, similar to the suspended Storefront Improvement Program.

For further information on how PMA helps owners consider reuse options, navigate the regulations, and take advantage of available benefits – please visit our website to review our multidisciplinary projects and comprehensive architecture, building envelope science, and planning services.

Written by Kristen Minor, Associate, Preservation Planner

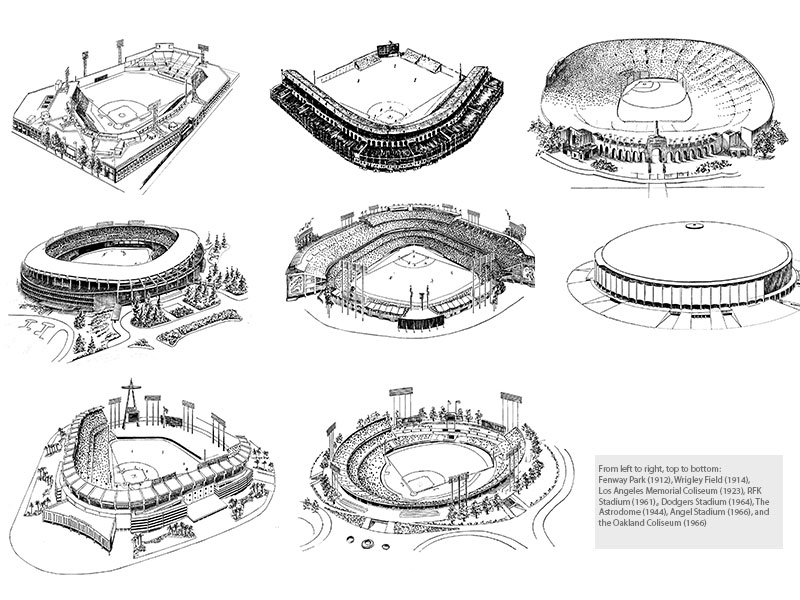

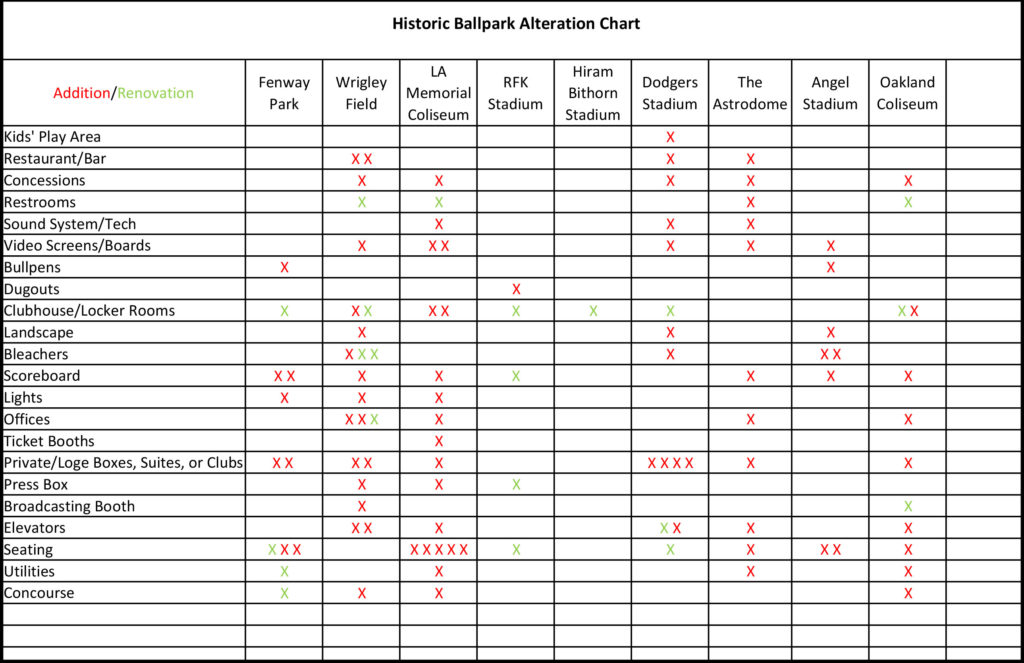

Since its creation in 1862, the ballpark has continued to have an influential impact on those who experience it. This impact is not only measured by heritage tourism to these sites, like Fenway Park or Wrigley Field, but also by how they are preserved. In some cases, such as Fenway Park, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, ballparks are preserved in a very traditional sense of the word. However, most ballparks never have the opportunity to reach the benchmarks needed to be preserved according to these preservation standards and are therefore preserved through a variety of alternative preservation methods. These methods, which span the spectrum from preserving a ballpark through the presentation of their original objects in a museum to the preservation of existing relics in their original location, such as Tiger Stadium’s center field flag pole, have given a large segment of our society an opportunity to continue their emotional discourse with this architectural form. Yet, the results of these preservation methods are commonly only the conclusion to a greater act of ceremony and community involvement that preludes them.

Since its creation in 1862, the ballpark has continued to have an influential impact on those who experience it. This impact is not only measured by heritage tourism to these sites, like Fenway Park or Wrigley Field, but also by how they are preserved. In some cases, such as Fenway Park, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, ballparks are preserved in a very traditional sense of the word. However, most ballparks never have the opportunity to reach the benchmarks needed to be preserved according to these preservation standards and are therefore preserved through a variety of alternative preservation methods. These methods, which span the spectrum from preserving a ballpark through the presentation of their original objects in a museum to the preservation of existing relics in their original location, such as Tiger Stadium’s center field flag pole, have given a large segment of our society an opportunity to continue their emotional discourse with this architectural form. Yet, the results of these preservation methods are commonly only the conclusion to a greater act of ceremony and community involvement that preludes them.  Part of this ceremony and community involvement is the simple act of participating in the ritual that is the game itself. Most often this is conducted through observation, as society, architecture, and sport become one for nine innings. However, other documented examples of ceremony and community involvement that express the level of compassion our society has for ballparks include ritualistic acts, such as the digging up and transferring of home plate. In some cases, this ritual has included the transferring of home plate via helicopter, limousines, or police escort. Ceremonies like this have also included, for better or worse, the salvaging of dirt, sod, and other relics from a ballpark to be, either cherished as a memento or repurposed in new stadiums. Nevertheless, these examples of ceremony only scratch the surface of the depth that is our society’s infatuation with sport and its architecture, more specifically the ballpark.

Part of this ceremony and community involvement is the simple act of participating in the ritual that is the game itself. Most often this is conducted through observation, as society, architecture, and sport become one for nine innings. However, other documented examples of ceremony and community involvement that express the level of compassion our society has for ballparks include ritualistic acts, such as the digging up and transferring of home plate. In some cases, this ritual has included the transferring of home plate via helicopter, limousines, or police escort. Ceremonies like this have also included, for better or worse, the salvaging of dirt, sod, and other relics from a ballpark to be, either cherished as a memento or repurposed in new stadiums. Nevertheless, these examples of ceremony only scratch the surface of the depth that is our society’s infatuation with sport and its architecture, more specifically the ballpark.  Ceremonial Acts & Community Involvement Efforts

Ceremonial Acts & Community Involvement Efforts  Led by the Friends of Civic Stadium president, Dennis Hebert, the organization held a wake in honor of their lost historic building. The wake, intimate in size, resembled a jazz funeral with a procession to the remains of the ballpark led by the One More Time Marching Band. Once at the site of the ballpark, there were multiple ritualistic acts that mimicked traditional funeral ceremonies. These acts included a moment of silence, a passionate speech by Dennis Hebert, and the always haunting rendition of Amazing Grace on bagpipes. After the ceremony, the Friends of Civic Stadium and the friends of Friends of Civic Stadium proceeded back to Tsunami Books where they continued to express their condolences and fond memories of the lost historic ballpark.

Led by the Friends of Civic Stadium president, Dennis Hebert, the organization held a wake in honor of their lost historic building. The wake, intimate in size, resembled a jazz funeral with a procession to the remains of the ballpark led by the One More Time Marching Band. Once at the site of the ballpark, there were multiple ritualistic acts that mimicked traditional funeral ceremonies. These acts included a moment of silence, a passionate speech by Dennis Hebert, and the always haunting rendition of Amazing Grace on bagpipes. After the ceremony, the Friends of Civic Stadium and the friends of Friends of Civic Stadium proceeded back to Tsunami Books where they continued to express their condolences and fond memories of the lost historic ballpark.

Buildings constructed before 1965 have reached the age of eligibility for being considered historic by the standards of the National Register. That means that much of Modern Architecture, the general period ranging from 1950 through 1970, is historic, or soon will be considered historic as the 50-year mark is crossed. As historians assess and study Modern Architecture, we provide ever more precise descriptions and terms to describe the sub-styles and variations within the large umbrella term, “Modern.” As in taxonomy, which classifies and categorizes living organisms, we can recognize and assign groups of similar resources together for study.

Buildings constructed before 1965 have reached the age of eligibility for being considered historic by the standards of the National Register. That means that much of Modern Architecture, the general period ranging from 1950 through 1970, is historic, or soon will be considered historic as the 50-year mark is crossed. As historians assess and study Modern Architecture, we provide ever more precise descriptions and terms to describe the sub-styles and variations within the large umbrella term, “Modern.” As in taxonomy, which classifies and categorizes living organisms, we can recognize and assign groups of similar resources together for study.

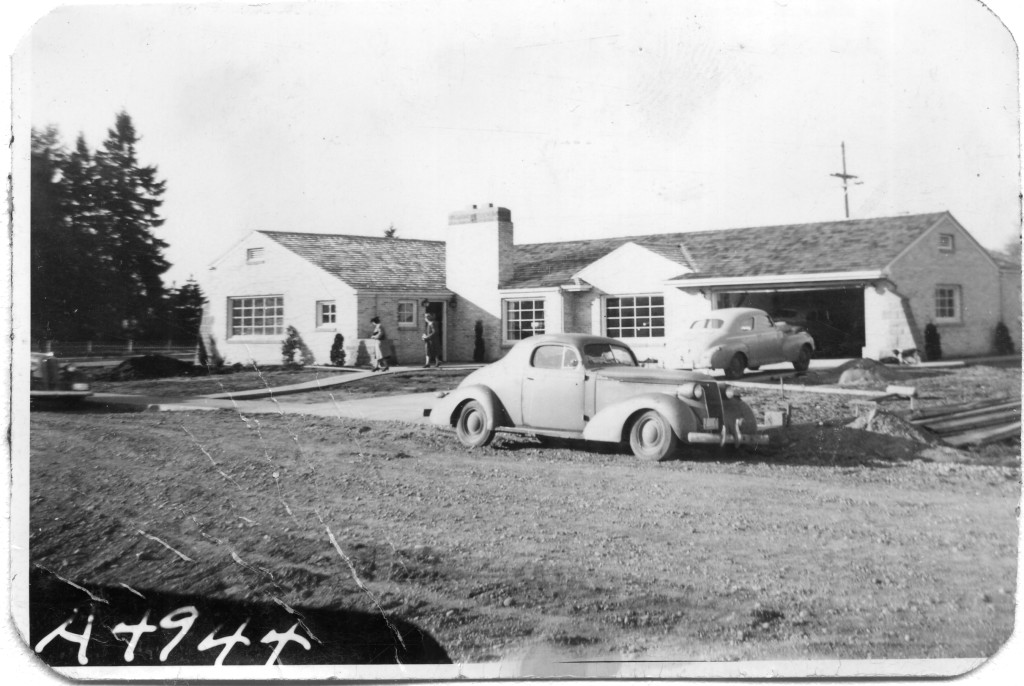

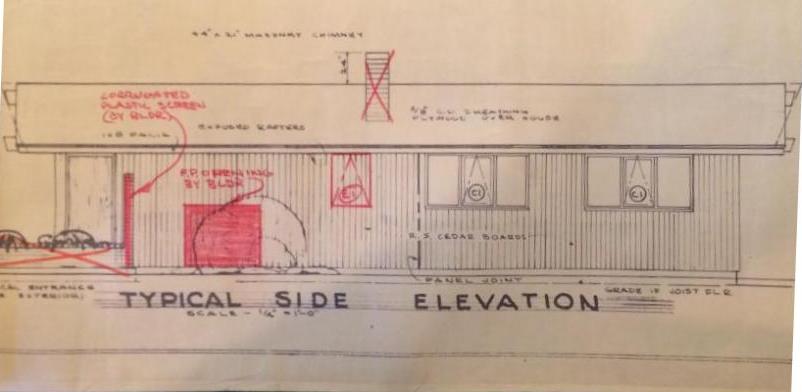

The Olympia survey classified the first grouping of styles as those that are transitional. Transitional Modern styles have some elements of Modern and some elements of more traditional architecture. Windows might be vertically-oriented, double-hung wood windows (traditional) rather than having horizontal proportions (Modern). A roof might be a moderate pitch, with minimal overhangs (traditional), rather than a shallow pitch with outwardly-extending gables (Modern). In Olympia, 37% of the houses surveyed were Modern Minimal Traditional, by far the most prevalent Transitional Modern style.

The Olympia survey classified the first grouping of styles as those that are transitional. Transitional Modern styles have some elements of Modern and some elements of more traditional architecture. Windows might be vertically-oriented, double-hung wood windows (traditional) rather than having horizontal proportions (Modern). A roof might be a moderate pitch, with minimal overhangs (traditional), rather than a shallow pitch with outwardly-extending gables (Modern). In Olympia, 37% of the houses surveyed were Modern Minimal Traditional, by far the most prevalent Transitional Modern style.  Ranch style architecture is the style that architecture critics have generally spurned, since houses were often constructed by contractors without architect’s involvement. Ranch buildings are broad, one-story, and horizontal in overall proportion. They have an attached garage which faces the street and is part of the overall form of the house, and almost always a large picture window facing the street as well. Cladding is used to accentuate the horizontal lines of the house, so there is often a change in material at the lower part of the front façade- brick veneer was a popular choice. Many of the sub-styles of Ranch architecture are “styled” Ranch houses, meaning that elements from another style of architecture were placed on a Ranch form building. One example is Storybook Ranch, which uses “gingerbread” trim, dormers or a cross-gable, and sometimes diamond-pane windows. Are these decorated sub-styles still part of the canon of Modern Architecture? In many ways, they are more Post-Modern than Modern, but that distinction is worthy of an involved discussion of its own.

Ranch style architecture is the style that architecture critics have generally spurned, since houses were often constructed by contractors without architect’s involvement. Ranch buildings are broad, one-story, and horizontal in overall proportion. They have an attached garage which faces the street and is part of the overall form of the house, and almost always a large picture window facing the street as well. Cladding is used to accentuate the horizontal lines of the house, so there is often a change in material at the lower part of the front façade- brick veneer was a popular choice. Many of the sub-styles of Ranch architecture are “styled” Ranch houses, meaning that elements from another style of architecture were placed on a Ranch form building. One example is Storybook Ranch, which uses “gingerbread” trim, dormers or a cross-gable, and sometimes diamond-pane windows. Are these decorated sub-styles still part of the canon of Modern Architecture? In many ways, they are more Post-Modern than Modern, but that distinction is worthy of an involved discussion of its own.  The Olympia Mid-Century Residential survey found over half the resources surveyed to be Ranch or variants of Ranch style. 31% of the surveyed homes were identified as simply Ranch, with another 11% Early Ranch, 9% Contemporary Ranch, 4% Split-Level or Split-Entry, and 4% one of the “Styled” Ranch variations. Sheer numbers alone remind us that the Ranch is deserving of study and shows us how the majority of middle-class Americans lived. As Alan Hess writes in his book Ranch House,

The Olympia Mid-Century Residential survey found over half the resources surveyed to be Ranch or variants of Ranch style. 31% of the surveyed homes were identified as simply Ranch, with another 11% Early Ranch, 9% Contemporary Ranch, 4% Split-Level or Split-Entry, and 4% one of the “Styled” Ranch variations. Sheer numbers alone remind us that the Ranch is deserving of study and shows us how the majority of middle-class Americans lived. As Alan Hess writes in his book Ranch House,

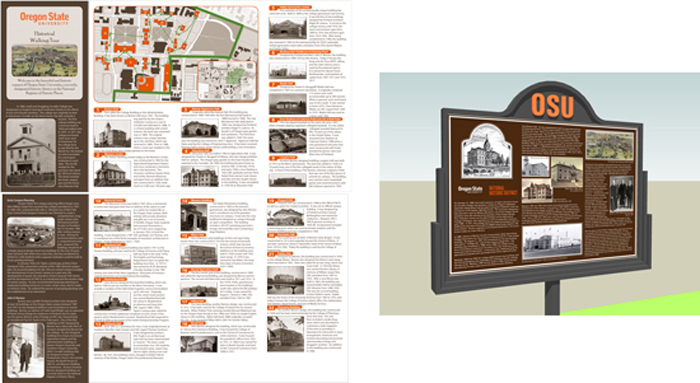

PMA has been involved with several architectural planning projects that center on significant structures from the Mid-Century Modern era. These projects surveyed and documented hundreds of architecturally significant structures that revolutionized architecture and design throughout the 20th century. On the surface such planning projects can be difficult for a wide audience to understand and appreciate because the final project is not a new or renovated building(s). What better opportunity then, for graphic design to communicate and connect the significance of the project and its structures. For these projects, project logos and marketing collateral were designed as the visual symbols that communicate the entire identity of the projects. While both projects surveyed Mid-Century structures one focused on residential structures while the other did not. Both logos use form with text and color to help shape the sense of which type of mid-century modern structures were surveyed.

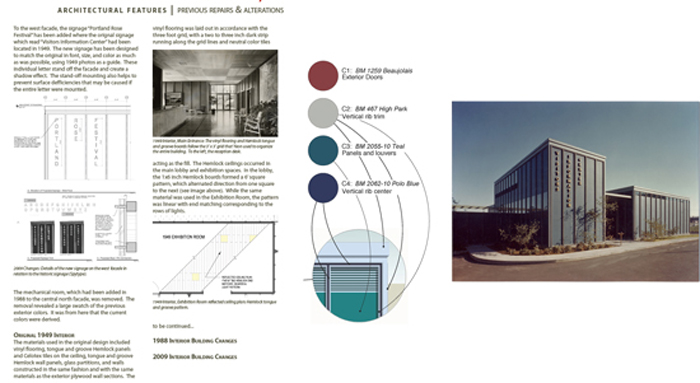

PMA has been involved with several architectural planning projects that center on significant structures from the Mid-Century Modern era. These projects surveyed and documented hundreds of architecturally significant structures that revolutionized architecture and design throughout the 20th century. On the surface such planning projects can be difficult for a wide audience to understand and appreciate because the final project is not a new or renovated building(s). What better opportunity then, for graphic design to communicate and connect the significance of the project and its structures. For these projects, project logos and marketing collateral were designed as the visual symbols that communicate the entire identity of the projects. While both projects surveyed Mid-Century structures one focused on residential structures while the other did not. Both logos use form with text and color to help shape the sense of which type of mid-century modern structures were surveyed.  Following our planning projects centered on Mid-Century Modern architecture, PMA provided graphic design services for the renovation of the John Yeon designed Rose Festival Headquarters building (former Visitors Information Center). For this project, typography and color were the focal points for communicating the next chapter in this buildings life-cycle. The new graphics, color, and signage produced pay homage to the original design, while being entirely their own.

Following our planning projects centered on Mid-Century Modern architecture, PMA provided graphic design services for the renovation of the John Yeon designed Rose Festival Headquarters building (former Visitors Information Center). For this project, typography and color were the focal points for communicating the next chapter in this buildings life-cycle. The new graphics, color, and signage produced pay homage to the original design, while being entirely their own.