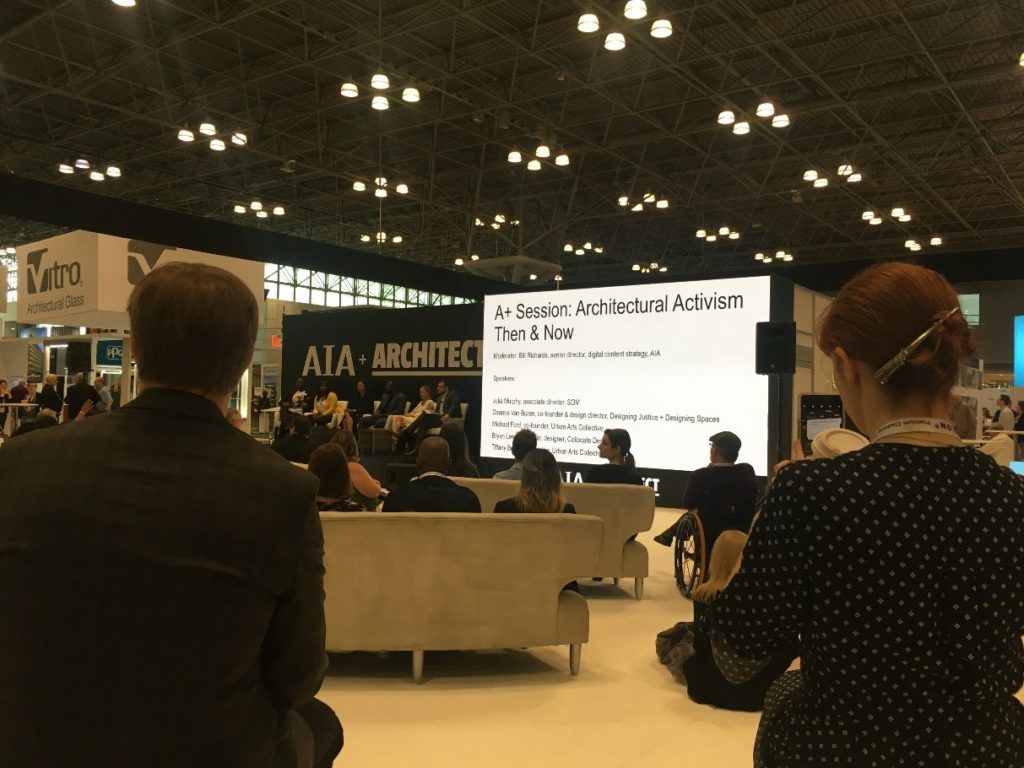

When stepping into the AIA Annual Conference at the Javits Center in NYC this year, I began to question the theme of the conference, a “Blueprint For Better Cities.” The expansive expo center sprawled out on three levels with thousands of booths promoting their products, from software to interiors to exteriors, but the one thing missing was representation from community groups or visible connection to the place of NYC.

Of course, the Javits Center adequately represents the grand nature of NYC amidst the building boom currently happening in Hudson Yards. It is hard to imagine anything but extravagant wealth when passing by the $150 million stairway to nowhere, aka the “Vessel” being constructed across the street. In a time of such great wealth disparity, what role do architects play in gentrifying our cities and creating safe public spaces for those without wealth and privilege? I believe architects continue to have a large impact on the growth of our cities and it is important to check our ethics as professionals on the impacts made in communities that may not be represented. The AEC industry seems to be expanding in exponential ways and defining our cities at a faster and faster pace, so conversations on equity and inclusion need to be brought to the forefront. Even though my first impression walking into the AIA conference at the Javits Center was not one of equity and inclusion, there were some great speakers bringing the conversation back to these important topics.

DESIGNERS ADDRESSING EQUITY IN THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

One session on Architectural Activism included a panel with Deanna Van Buren of Designing Justice + Designing Spaces, Bryan Lee of Colloqate, and Michael Ford of Hip Hop Architecture. These designers are addressing equity in the built environment and setting new standards for the profession.

Byran Lee reminds architects to think about the communities’ cultures when designing and not to perpetuate systems of oppression. Architects have the ability to change the built environment and also be advocates for the communities in which they work. Laws that allow the victimization of marginalized communities need to be challenged. Public spaces which should be the democratic spaces available to all people are made unsafe to communities of color because of ambiguous laws around vagrancy and other systems of oppression. Understanding the needs of communities in which you are working in paramount. Architects can start by supporting marginalized communities through youth education, advocacy for groups with less priviledge, and equitiable policy and placemaking.

Michael Ford has been working on the youth education component of architectural activism. Hip Hop Architect facilitates youth camps that introduce design, architecture, place making through the expression of hiphop culture. The camps provide an opportunity for youth of underrepresented populations to learn about the architectural practice and reinvision the future of our built environment. A factor in the lack of diversity in architecture is lack of accessiblity to the field, and this program strives to provide that support to youth.

Deanna Van Buren talked of her work around restorative justice and restorative economics, exploring alternative to prisons and addressing the root causes of mass incarceration. Restorative justice is statistically proven to build empathy and decrease recurring offenses by 75%, while allowing for reconciliation and healing. Deanna reiterated that prisons are the worst form of architecture, created to express the harm that we are doing on another. Altnernatives presented were popup resources villages that provide services to isolated communities and peacemaking centers that use Native American practices for healing communities that have experience the trauma of violence and racial oppression.

Many speakers recalled quotes from Whitney Young Jr when talking about equity in the architecture profession, especially from his poignant speech regarding equity at the 1968 American Institute of Architects Conference in Portland. A well quoted statement was “[A]s a profession, you are not a profession that has distinguished itself by your social and civic contributions to the cause of civil rights, and I am sure this has not come to you as any shock. You are most distinguished by your thunderous silence and your complete irrelevance.”

LANGUAGE AROUND ETHICAL AND EQUITABLE DESIGN

I would argree that the profession as a whole still struggles with its social and civic contributions, even though there are some great leaders as mentioned previously. Currently, the trend in most large cities is gentrification resulting in loss of community connections and a huge housing crisis. Do the ethics of architecture speak towards our professional responsibilty to provide for the well being and safety for all within the communities in which we design for? In the AIA Code of Ethics, the only somewhat relevant bylaw I found was “In performing professional services, Members should advocate the design, construction, and operation of sustainable buildings and communities.” Perhaps the lack of language around ethical and equitable design is why it seems so lacking within the built environment. There needs to be a shift.

Large firms may promote their community work by supporting employees to volunteer a couple days of the year, or provide pro-bono design services. This approach is too compartmentalized and does not build the disruptive change needed to challenge systems of oppression in our built environment. These one-off gestures of pro-bono work can easily be perceived by communities as a savior complex instead of community building. The factors that push architects to design without community in mind needs to be resisted by the industry. Rather, more efforts need to be made so our ethical responsibilities to the public outweigh the profit driven interest groups’ needs that are currently prevalent in our industry. The sustainability movement has started to touch on some of our ethical responsibilities for healthier spaces, but these efforts are not preventing people from losing their homes, connection to place, civic amenities, and much more. There is much work to be done. To promote equity and inclusion for all when designing spaces, I believe we must work on our role as architects to listen, learn, be humble, engage, teach, and provide support and advocacy that serves the communities in which we are working.

Written by Hali Knight Assoc. AIA, Designer

Author’s note: I am a historian and historic preservation who has had many seats at the historic preservation table, ranging from consultant to SHPO staff. I have recently undertaken a deep study of where we are in historic preservation and how we might practice in the field differently in the near future. The retrospective look that was taken at the 50th anniversary in 2016 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) provided a lot of dialog but no clear ways forward that are any different than what we have done in the past. Based on the assumption that there are additional effective practices we should explore, bolstered by a growing interest in Critical Heritage Theory, I’m convinced that we can add effective practices within the existing regulatory framework – particularly if we base them on more robust theories of historic preservation. Therefore, we have important work to do together to develop and apply practice theories for heritage work in the public sector. This essay is one of several that will explore how our practice can be different.

Author’s note: I am a historian and historic preservation who has had many seats at the historic preservation table, ranging from consultant to SHPO staff. I have recently undertaken a deep study of where we are in historic preservation and how we might practice in the field differently in the near future. The retrospective look that was taken at the 50th anniversary in 2016 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) provided a lot of dialog but no clear ways forward that are any different than what we have done in the past. Based on the assumption that there are additional effective practices we should explore, bolstered by a growing interest in Critical Heritage Theory, I’m convinced that we can add effective practices within the existing regulatory framework – particularly if we base them on more robust theories of historic preservation. Therefore, we have important work to do together to develop and apply practice theories for heritage work in the public sector. This essay is one of several that will explore how our practice can be different.