First presented at RCI 2015 Symposium on Building Envelope Technology, Nashville, TN

Background

When it was completed, Grant High School was typical of the high schools constructed by Portland Public Schools in the pre-World War II era. In addition to being an extensible school, including educational buildings constructed between 1923 and 1970, the school was also reflective of fire-proof construction through its use of a reinforced concrete structure with brick in-fill. (Portland Public Schools, Historic Building Assessment, Entrix, October 2009)

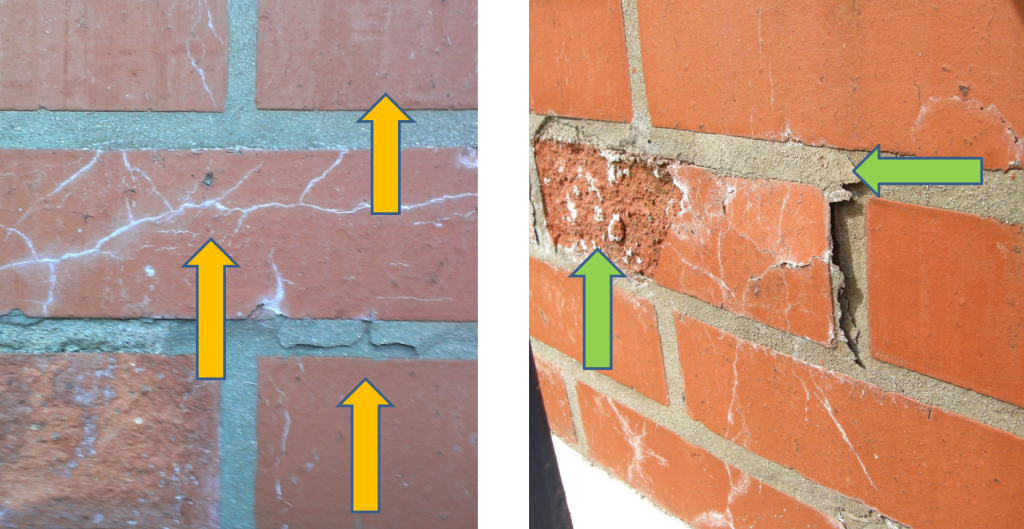

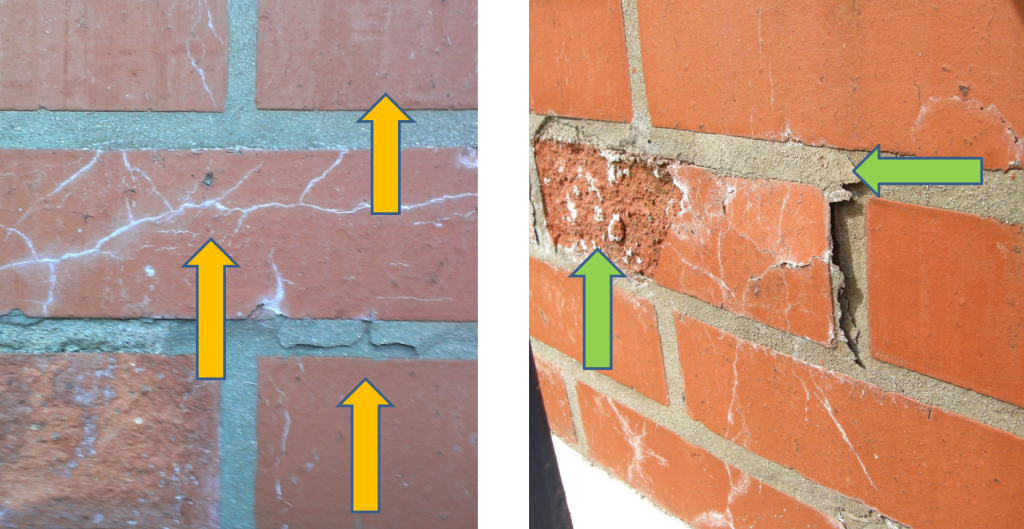

Over the last fifteen years, Portland Public Schools (PPS) noted an accelerated degree of masonry face spalling on the original 1923 main building and 1923 Old Gym particularly when adjacent to concentrated sources of surface water. Other areas of spalling were not as obvious including protected wall surfaces. The masonry spalling was not occurring on later additions including the north wing (circa 1925), south wing (circa 1927), and auditorium building (circa 1927). Upon closer visual examination, it was observed that individual units were failing in isolated protected areas of the wall surface. Failures in such areas could not be accounted for under direct correlation of heavy water intrusion and typical failure mechanisms.

The failure of the brick was potentially due to a number of separate or cumulative conditions including 1) excessive water uptake by the brick; 2) sub-fluorescence expansion of salts in the masonry, 3) freeze thaw; 4) low quality of the original 1923 brick; and 5) the application of surface sealers preventing water migrating to the exterior surface.

Field Investigation

In order to determine if the damage to the masonry was deeper than the surface, several wall-lets, an invasive exterior wall opening, were performed confirming the assembly of a multi-wythe masonry wall constructed in a typical fully bedded bond course with interlocking headers and no cavities between the first three brick courses. Hooked shaped, 3/32” gage, steel wire masonry ties in alternating courses and approximately twelve inches (12”) on center ties were found to be in good condition with no deterioration. The absence of corrosion on the in place brick wire ties indicated that little moisture was present inside the multi-wythe wall.

As a result of the hypothesis and field observations, it was prudent to conduct a series of lab tests to the brick, mortar, and patch materials to assist in the determination of 1) the quality of the brick; 2) the physical composition of the brick; 3) the quantity of naturally occurring compounds in the masonry and mortar, particularly salts in the masonry; and 4) the quality of the mortar. The findings would help narrow the potential cause of the spalling and lead to a more focused repair and maintenance process. Bricks were removed for testing of Initial Rate of Absorption (IRA – a test for susceptibility to water saturation) freeze thaw testing, and petrographic analysis, a way to determine the inherent properties of the clay and manufacturing process. Both pointing and bedding mortar samples, as well as, the previous patching material were removed and also tested. To rule out damage caused by maintenance procedures, faces of the brick material were sent to determine if sealants were used on the brick and, if present, determine the sealant chemical makeup. The presence of a surface coating may lead to retention of water within the brick and thus prevent natural capillary flow, natural drying, and water evaporation.

Testing & Results

Samples sent to the lab for coating assessment were analyzed via episcopic light microscopy, and Fourier- Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) per ASTM D1245 and ASTM E1252. The results found no hydrocarbon or organic formulations used on the surface of the brick refuting the hypothesis of a surface sealer.

Following modified ASTM standards, a 24-hr immersion and 5-hr boil absorption test on the brick were performed. The brick have a very low percent of total absorption at 9.5% for the 5-hr boil and 7.5% for the 24-hr test. The maximum saturation coefficient is 0.79 which is 0.01 over the maximum requirements for Severe Weathering bricks recommended for Portland climate (ASTM C216-07a Table 1). The Initial Rate of Absorption (IRA) is 5.7g/min/30in2 which equates to a very low suction brick or brick with low initial rates of absorption. The freeze thaw durability tests resulted in passing performance. All of these tests refuted the hypothesis that freezing temperatures were the cause of masonry spalling.

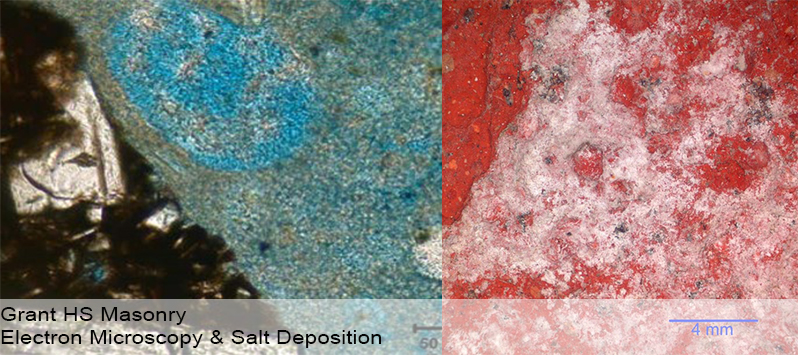

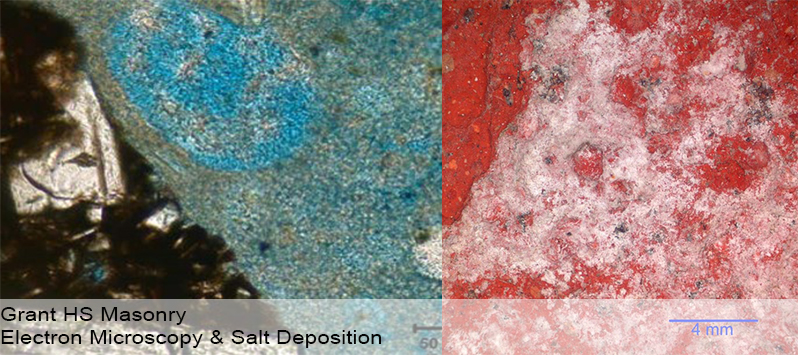

A brick material analysis was performed in general conformance with ASTM C856, ASTM C1324 (masonry mortar) and included petrographic analysis, chemical analyses, x-ray diffraction and thermogravimetric analysis. Samples were analyzed under a polarized light microscope for information such as materials ratio and presence or absence of different deterioration mechanisms. These tests were used to assess the overall quality of material, presence of inherent salts, excessive retempering, cracking, ettringite formation, and potential alkali‐silica reactivity.

The Petrographic Characterization resulted in the most unusual findings and the most relevant results related to the observed failures. The polarized light microscope indicated carbonate based salt crystals seeping into the masonry from the mortar. No sulfate based salts, typically associated with the clays used for making brick, were present. Furthermore the inherent properties of the brick showed very small rounded voids and interconnected planer voids. Planner voids result from poor compaction during the raw clay extrusion process prior to firing.

Performance of brick in the field is a result of both material properties and resistance to micro-climates within the brick’s capillary void structure which cannot be repeated in the lab. Studies have shown a connection between small voids in the material property and susceptibility to longer water retention near the surface. With natural absorption properties, the brick is taking in a small quantity of water in very small pores. 24-hour immersion results are very low (7.5%). Publication of more in-depth studies correlates maximum saturation values for brick with low 24-hour immersion values. The effect of low immersion values and small quantities of absorbed water may increase the susceptibility in brick with small pore structure to freeze thaw failure.

The presence of salt migration out of the mortar and into the brick, plus small pore structure and low immersion values, combining with a cleavage plane resulting from manufacturing are contributing to the Grant High School brick spalls. Brick with smaller pores are less capable of absorbing the expansive forces of freezing water and drying salts. Interlaced pores creating linear plains parallel with the face of the brick create stress failure points resulting in surface spalling. Since the characteristics of the brick resulted from the firing and manufacturing process, the brick will remain susceptible to the failure mechanisms.

Conclusion

Field observations of masonry failures generally correspond with known failure mechanisms. However, it is not unusual that further analysis is necessary to confirm in-field performance and that typical laboratory test results are in conflict with in-situ performance.

The best corrective action is to minimize the amount of surface water and proper mortar joints and mortar composition. Additional spalls are likely to occur in the future due to the accumulation of expansive forces over a long period of time. Replacement of the spalled bricks is recommended over further patching. Leaving spalled brick in place will continue to worsen the condition over time and affect adjacent brick.

Written by Peter Meijer, AIA, NCARB, Principal

20% Rehabilitation Tax Credit

20% Rehabilitation Tax Credit

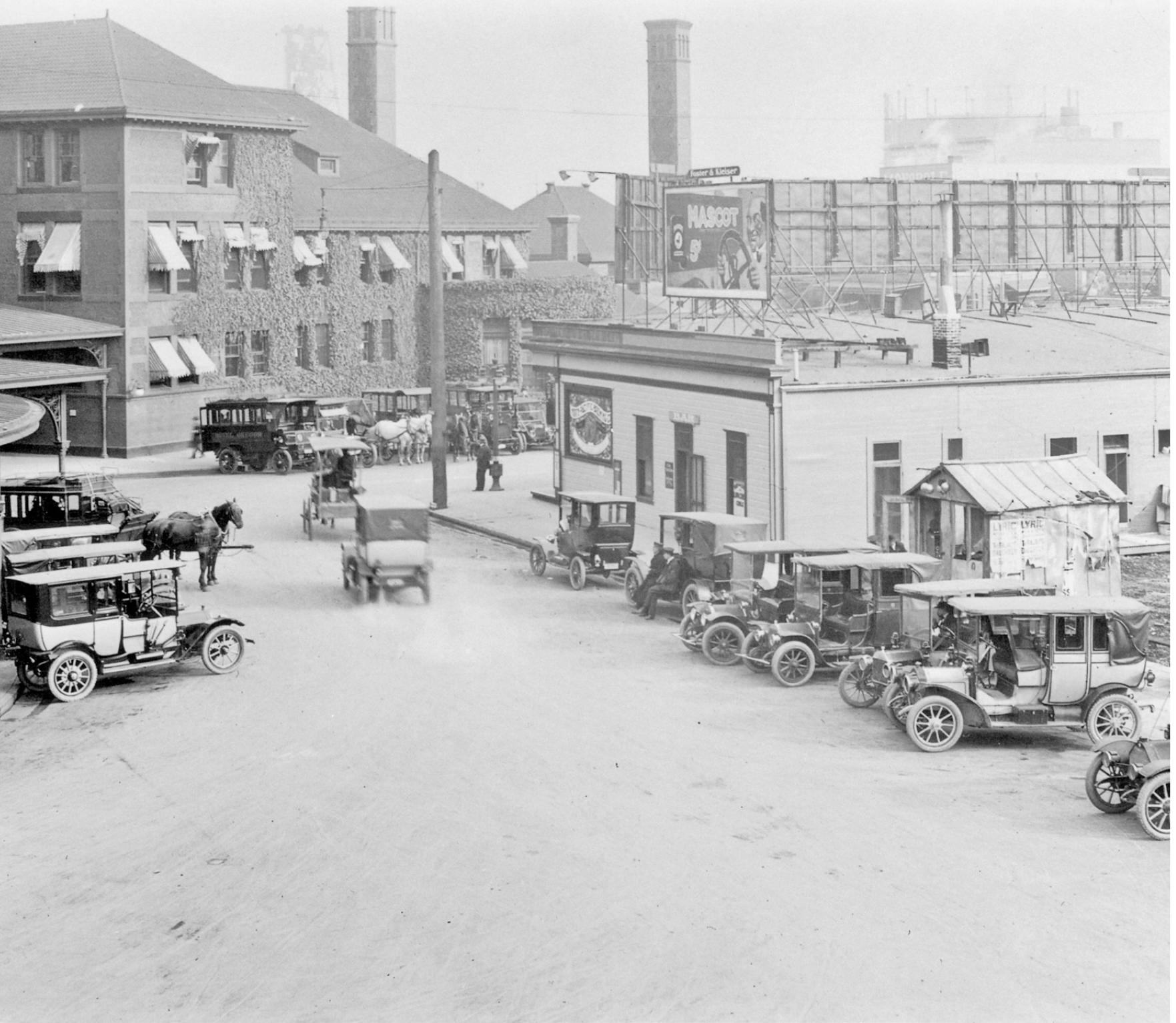

Since its creation in 1862, the ballpark has continued to have an influential impact on those who experience it. This impact is not only measured by heritage tourism to these sites, like Fenway Park or Wrigley Field, but also by how they are preserved. In some cases, such as Fenway Park, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, ballparks are preserved in a very traditional sense of the word. However, most ballparks never have the opportunity to reach the benchmarks needed to be preserved according to these preservation standards and are therefore preserved through a variety of alternative preservation methods. These methods, which span the spectrum from preserving a ballpark through the presentation of their original objects in a museum to the preservation of existing relics in their original location, such as Tiger Stadium’s center field flag pole, have given a large segment of our society an opportunity to continue their emotional discourse with this architectural form. Yet, the results of these preservation methods are commonly only the conclusion to a greater act of ceremony and community involvement that preludes them.

Since its creation in 1862, the ballpark has continued to have an influential impact on those who experience it. This impact is not only measured by heritage tourism to these sites, like Fenway Park or Wrigley Field, but also by how they are preserved. In some cases, such as Fenway Park, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, ballparks are preserved in a very traditional sense of the word. However, most ballparks never have the opportunity to reach the benchmarks needed to be preserved according to these preservation standards and are therefore preserved through a variety of alternative preservation methods. These methods, which span the spectrum from preserving a ballpark through the presentation of their original objects in a museum to the preservation of existing relics in their original location, such as Tiger Stadium’s center field flag pole, have given a large segment of our society an opportunity to continue their emotional discourse with this architectural form. Yet, the results of these preservation methods are commonly only the conclusion to a greater act of ceremony and community involvement that preludes them.  Part of this ceremony and community involvement is the simple act of participating in the ritual that is the game itself. Most often this is conducted through observation, as society, architecture, and sport become one for nine innings. However, other documented examples of ceremony and community involvement that express the level of compassion our society has for ballparks include ritualistic acts, such as the digging up and transferring of home plate. In some cases, this ritual has included the transferring of home plate via helicopter, limousines, or police escort. Ceremonies like this have also included, for better or worse, the salvaging of dirt, sod, and other relics from a ballpark to be, either cherished as a memento or repurposed in new stadiums. Nevertheless, these examples of ceremony only scratch the surface of the depth that is our society’s infatuation with sport and its architecture, more specifically the ballpark.

Part of this ceremony and community involvement is the simple act of participating in the ritual that is the game itself. Most often this is conducted through observation, as society, architecture, and sport become one for nine innings. However, other documented examples of ceremony and community involvement that express the level of compassion our society has for ballparks include ritualistic acts, such as the digging up and transferring of home plate. In some cases, this ritual has included the transferring of home plate via helicopter, limousines, or police escort. Ceremonies like this have also included, for better or worse, the salvaging of dirt, sod, and other relics from a ballpark to be, either cherished as a memento or repurposed in new stadiums. Nevertheless, these examples of ceremony only scratch the surface of the depth that is our society’s infatuation with sport and its architecture, more specifically the ballpark.  Ceremonial Acts & Community Involvement Efforts

Ceremonial Acts & Community Involvement Efforts  Led by the Friends of Civic Stadium president, Dennis Hebert, the organization held a wake in honor of their lost historic building. The wake, intimate in size, resembled a jazz funeral with a procession to the remains of the ballpark led by the One More Time Marching Band. Once at the site of the ballpark, there were multiple ritualistic acts that mimicked traditional funeral ceremonies. These acts included a moment of silence, a passionate speech by Dennis Hebert, and the always haunting rendition of Amazing Grace on bagpipes. After the ceremony, the Friends of Civic Stadium and the friends of Friends of Civic Stadium proceeded back to Tsunami Books where they continued to express their condolences and fond memories of the lost historic ballpark.

Led by the Friends of Civic Stadium president, Dennis Hebert, the organization held a wake in honor of their lost historic building. The wake, intimate in size, resembled a jazz funeral with a procession to the remains of the ballpark led by the One More Time Marching Band. Once at the site of the ballpark, there were multiple ritualistic acts that mimicked traditional funeral ceremonies. These acts included a moment of silence, a passionate speech by Dennis Hebert, and the always haunting rendition of Amazing Grace on bagpipes. After the ceremony, the Friends of Civic Stadium and the friends of Friends of Civic Stadium proceeded back to Tsunami Books where they continued to express their condolences and fond memories of the lost historic ballpark.

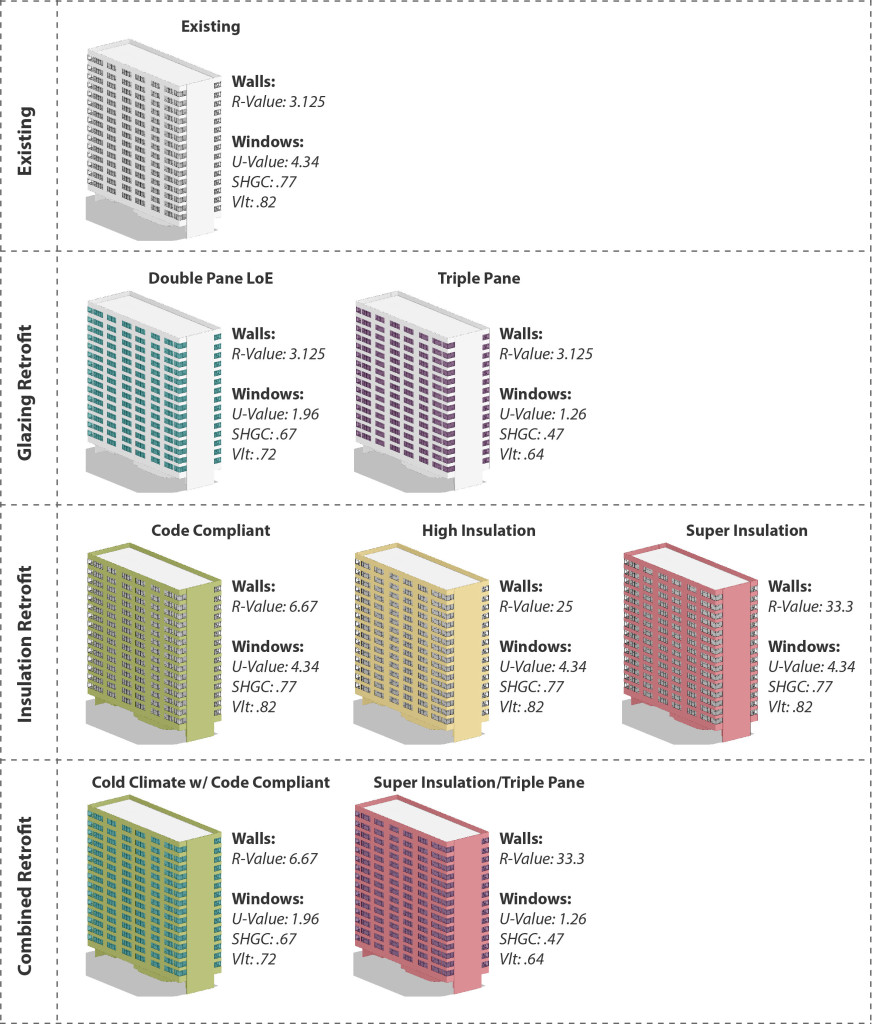

PMA recently performed an energy analysis study to answer that question. The project was to provide quantitative data on the energy savings associated with window replacement versus insulating exterior walls. We choose to study a structure on the brink of historic status – a 1960’s multi-story residential structure with large character defining view windows. The structure is composed of concrete walls, beams, floors, and columns with single pane aluminum windows. The existing building has approximately 36% glazing and no insulation.

PMA recently performed an energy analysis study to answer that question. The project was to provide quantitative data on the energy savings associated with window replacement versus insulating exterior walls. We choose to study a structure on the brink of historic status – a 1960’s multi-story residential structure with large character defining view windows. The structure is composed of concrete walls, beams, floors, and columns with single pane aluminum windows. The existing building has approximately 36% glazing and no insulation.  A wide range of constructions were chosen in order to see the full range of possible results. Future studies may focus on more refined material choices and a narrower set of parameters. The analysis was run in Autodesk Green Building Studio which is an excellent tool to perform basic energy models. While GBS does not allow for complex simulations it can quickly and accurately compare a variety of different design alternatives.

A wide range of constructions were chosen in order to see the full range of possible results. Future studies may focus on more refined material choices and a narrower set of parameters. The analysis was run in Autodesk Green Building Studio which is an excellent tool to perform basic energy models. While GBS does not allow for complex simulations it can quickly and accurately compare a variety of different design alternatives.

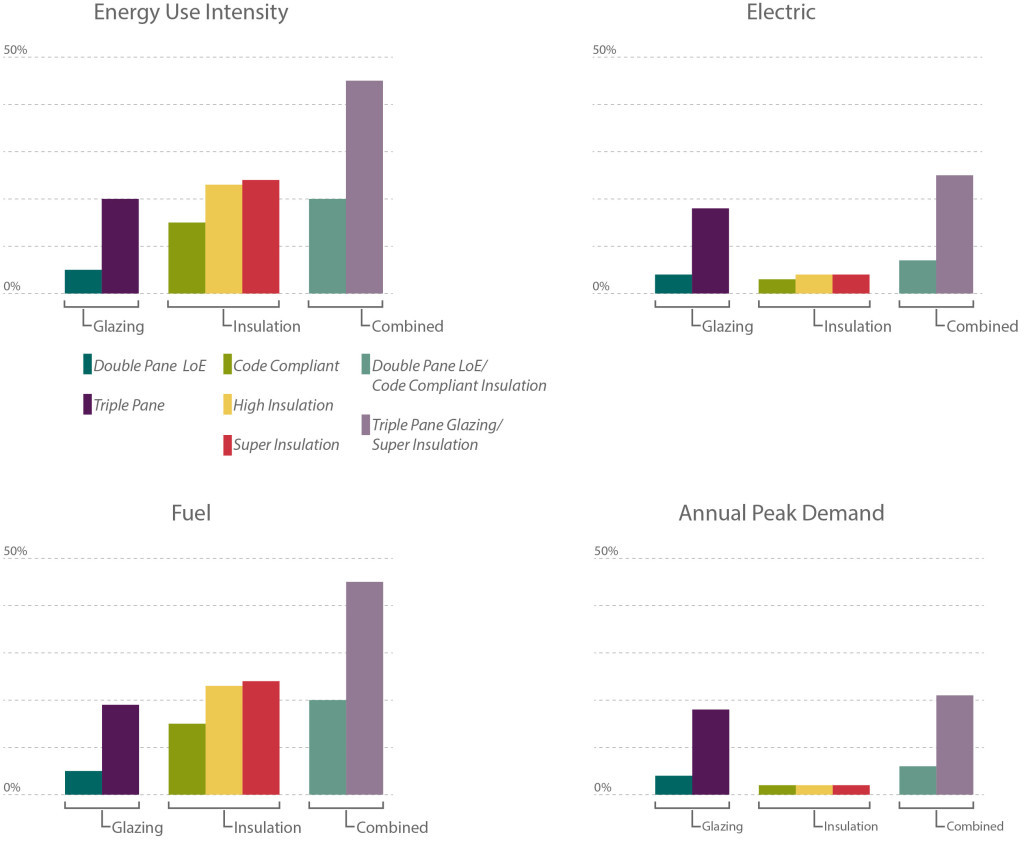

With current technologies the results indicate that adding insulation to a building has the most cost effective impact on energy performance. Installing new insulation is typically less expensive than window replacement and the results of this study show that Code Compliant (R-~7) insulation can have a significant impact on overall energy usage, outperforming Double Pane window replacement. Interestingly, the results also indicate that a High Insulation (R-25) retrofit performs better than a Combined Retrofit with Code Compliant Insulation (R-~7) and Double Pane Glass.

With current technologies the results indicate that adding insulation to a building has the most cost effective impact on energy performance. Installing new insulation is typically less expensive than window replacement and the results of this study show that Code Compliant (R-~7) insulation can have a significant impact on overall energy usage, outperforming Double Pane window replacement. Interestingly, the results also indicate that a High Insulation (R-25) retrofit performs better than a Combined Retrofit with Code Compliant Insulation (R-~7) and Double Pane Glass.

Greatly influenced by the 1936 publication of John Yeon’s Watzek House, Oregon architects began to experiment with wood skins and “Mt. Hood” entry facades reminiscent of Yeon’s design. The idea that wood was symbolic of Northwest character continued through the 1950s and 1960s mid-century modern aesthetics. Local architects like Francis Jacobberger, McCoy & Bradbury, Pietro Belluschi, and others crafter their designs from outside to inside using local species of wood while simultaneously using wood to express the structural elements.

Greatly influenced by the 1936 publication of John Yeon’s Watzek House, Oregon architects began to experiment with wood skins and “Mt. Hood” entry facades reminiscent of Yeon’s design. The idea that wood was symbolic of Northwest character continued through the 1950s and 1960s mid-century modern aesthetics. Local architects like Francis Jacobberger, McCoy & Bradbury, Pietro Belluschi, and others crafter their designs from outside to inside using local species of wood while simultaneously using wood to express the structural elements.

Well known Oregon artists, including Ray Grimm, a ceramists, created the dominating Tree of Life mosaic on the west façade. LeRoy Setziol, the “Father of Wood Carving in Oregon,” created the wood Stations of the Cross and baptismal font. Surprisingly Setziol was commissioned to execute the stained glass windows as well. And Lee Kelly, one of Portland’s best known metal sculptors, enriched the church with delicate displays of metal work both on the interior and exterior. Queen of Peace is a marvelous collaboration of architecture, art, and technical daring creating a wonderful display of Oregon indigenous mid-century religious architecture.

Well known Oregon artists, including Ray Grimm, a ceramists, created the dominating Tree of Life mosaic on the west façade. LeRoy Setziol, the “Father of Wood Carving in Oregon,” created the wood Stations of the Cross and baptismal font. Surprisingly Setziol was commissioned to execute the stained glass windows as well. And Lee Kelly, one of Portland’s best known metal sculptors, enriched the church with delicate displays of metal work both on the interior and exterior. Queen of Peace is a marvelous collaboration of architecture, art, and technical daring creating a wonderful display of Oregon indigenous mid-century religious architecture. Buildings constructed before 1965 have reached the age of eligibility for being considered historic by the standards of the National Register. That means that much of Modern Architecture, the general period ranging from 1950 through 1970, is historic, or soon will be considered historic as the 50-year mark is crossed. As historians assess and study Modern Architecture, we provide ever more precise descriptions and terms to describe the sub-styles and variations within the large umbrella term, “Modern.” As in taxonomy, which classifies and categorizes living organisms, we can recognize and assign groups of similar resources together for study.

Buildings constructed before 1965 have reached the age of eligibility for being considered historic by the standards of the National Register. That means that much of Modern Architecture, the general period ranging from 1950 through 1970, is historic, or soon will be considered historic as the 50-year mark is crossed. As historians assess and study Modern Architecture, we provide ever more precise descriptions and terms to describe the sub-styles and variations within the large umbrella term, “Modern.” As in taxonomy, which classifies and categorizes living organisms, we can recognize and assign groups of similar resources together for study.

The Olympia survey classified the first grouping of styles as those that are transitional. Transitional Modern styles have some elements of Modern and some elements of more traditional architecture. Windows might be vertically-oriented, double-hung wood windows (traditional) rather than having horizontal proportions (Modern). A roof might be a moderate pitch, with minimal overhangs (traditional), rather than a shallow pitch with outwardly-extending gables (Modern). In Olympia, 37% of the houses surveyed were Modern Minimal Traditional, by far the most prevalent Transitional Modern style.

The Olympia survey classified the first grouping of styles as those that are transitional. Transitional Modern styles have some elements of Modern and some elements of more traditional architecture. Windows might be vertically-oriented, double-hung wood windows (traditional) rather than having horizontal proportions (Modern). A roof might be a moderate pitch, with minimal overhangs (traditional), rather than a shallow pitch with outwardly-extending gables (Modern). In Olympia, 37% of the houses surveyed were Modern Minimal Traditional, by far the most prevalent Transitional Modern style.  Ranch style architecture is the style that architecture critics have generally spurned, since houses were often constructed by contractors without architect’s involvement. Ranch buildings are broad, one-story, and horizontal in overall proportion. They have an attached garage which faces the street and is part of the overall form of the house, and almost always a large picture window facing the street as well. Cladding is used to accentuate the horizontal lines of the house, so there is often a change in material at the lower part of the front façade- brick veneer was a popular choice. Many of the sub-styles of Ranch architecture are “styled” Ranch houses, meaning that elements from another style of architecture were placed on a Ranch form building. One example is Storybook Ranch, which uses “gingerbread” trim, dormers or a cross-gable, and sometimes diamond-pane windows. Are these decorated sub-styles still part of the canon of Modern Architecture? In many ways, they are more Post-Modern than Modern, but that distinction is worthy of an involved discussion of its own.

Ranch style architecture is the style that architecture critics have generally spurned, since houses were often constructed by contractors without architect’s involvement. Ranch buildings are broad, one-story, and horizontal in overall proportion. They have an attached garage which faces the street and is part of the overall form of the house, and almost always a large picture window facing the street as well. Cladding is used to accentuate the horizontal lines of the house, so there is often a change in material at the lower part of the front façade- brick veneer was a popular choice. Many of the sub-styles of Ranch architecture are “styled” Ranch houses, meaning that elements from another style of architecture were placed on a Ranch form building. One example is Storybook Ranch, which uses “gingerbread” trim, dormers or a cross-gable, and sometimes diamond-pane windows. Are these decorated sub-styles still part of the canon of Modern Architecture? In many ways, they are more Post-Modern than Modern, but that distinction is worthy of an involved discussion of its own.  The Olympia Mid-Century Residential survey found over half the resources surveyed to be Ranch or variants of Ranch style. 31% of the surveyed homes were identified as simply Ranch, with another 11% Early Ranch, 9% Contemporary Ranch, 4% Split-Level or Split-Entry, and 4% one of the “Styled” Ranch variations. Sheer numbers alone remind us that the Ranch is deserving of study and shows us how the majority of middle-class Americans lived. As Alan Hess writes in his book Ranch House,

The Olympia Mid-Century Residential survey found over half the resources surveyed to be Ranch or variants of Ranch style. 31% of the surveyed homes were identified as simply Ranch, with another 11% Early Ranch, 9% Contemporary Ranch, 4% Split-Level or Split-Entry, and 4% one of the “Styled” Ranch variations. Sheer numbers alone remind us that the Ranch is deserving of study and shows us how the majority of middle-class Americans lived. As Alan Hess writes in his book Ranch House,

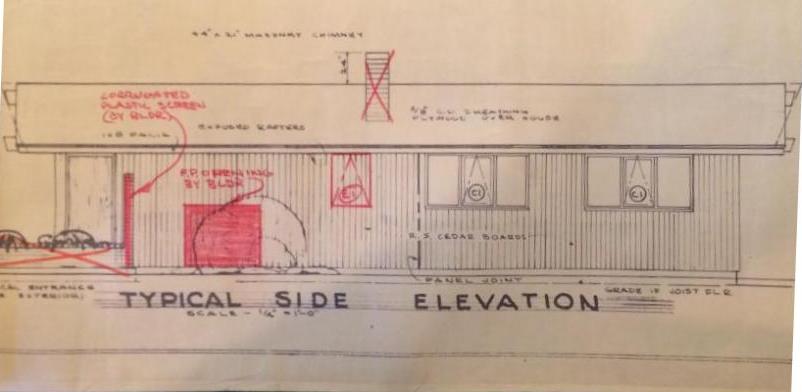

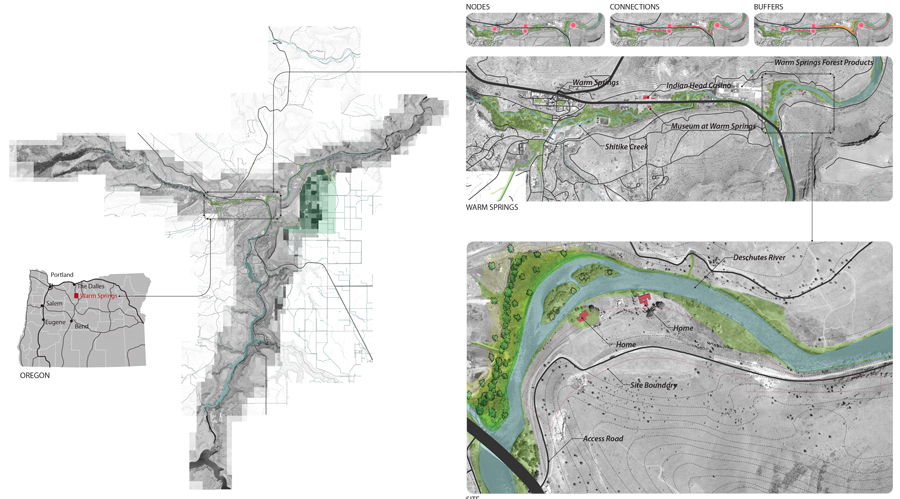

Projects that integrate building science, stewardship planning, and place design are simultaneously exciting and challenging. Any one of the three core concepts can drive the decision making process resulting in a number of solutions. Our current concepts for minimalist eco structures, or “Huts” in the beautiful High Desert of Eastern Oregon are a fantastic challenge.

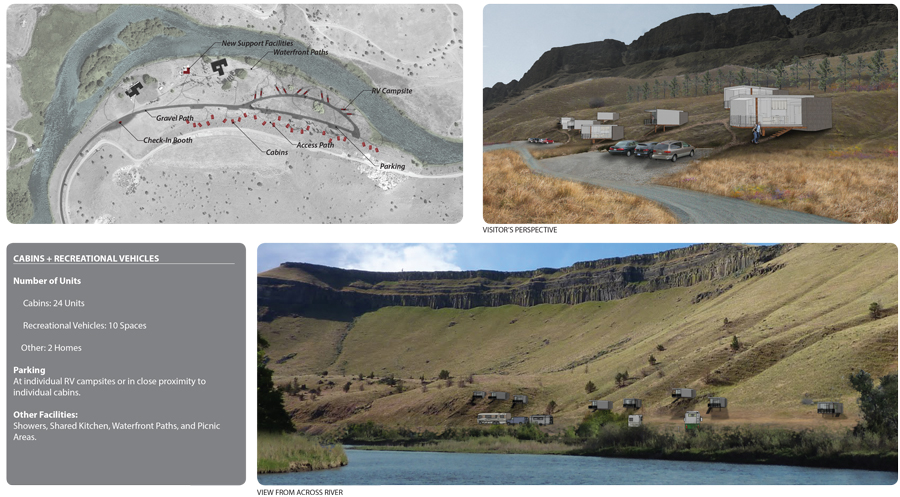

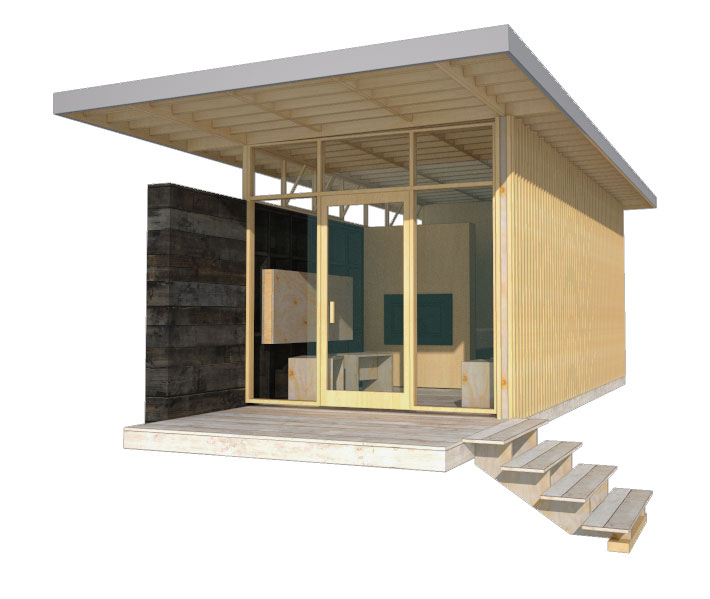

Projects that integrate building science, stewardship planning, and place design are simultaneously exciting and challenging. Any one of the three core concepts can drive the decision making process resulting in a number of solutions. Our current concepts for minimalist eco structures, or “Huts” in the beautiful High Desert of Eastern Oregon are a fantastic challenge. Working with the The Confederate Tribes of Warm Springs, PMA created a prototype model, easily constructed and assembled off site (test fit), then transported to the site and efficiently erected. The prototype was designed to be economical and constructed from lumber from the local lumber mill that produces products from high desert pines. A contemporary design style was chosen to harmonize with existing mid-century Belluschi homes on the property. Both the Belluschi homes and the Eco-Huts stand in contrast with the landscape and topography.

Working with the The Confederate Tribes of Warm Springs, PMA created a prototype model, easily constructed and assembled off site (test fit), then transported to the site and efficiently erected. The prototype was designed to be economical and constructed from lumber from the local lumber mill that produces products from high desert pines. A contemporary design style was chosen to harmonize with existing mid-century Belluschi homes on the property. Both the Belluschi homes and the Eco-Huts stand in contrast with the landscape and topography.

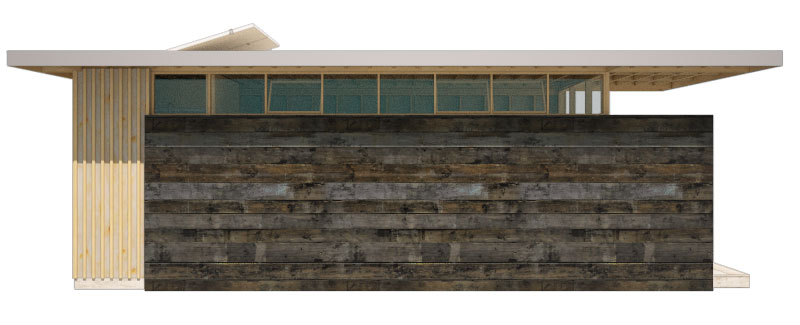

Conceived to have minimal footprints on the land, the Huts rest on piers elevating the floor above the land and accommodating the undulating landscape. A modular dimension was chosen permitting variation in the Eco-Hut sizes. The floor, walls, and roof planes are built off-site and tilted in place. Exterior stained wood material varying from plywood to sawn boards were chosen to harmonize with the High Desert landscape and be of minimal maintenance to the Tribes. Plywood panels are dressed with battens and either in-set from the wood framing or installed flush to the exterior. Sawn mill boards are stained dark desert grey and applied horizontally to create solid side walls atop of which are placed ribbon windows. The primary entry and view wall is a wood frame window and door façade. A deep roof overhang protects the interior from solar gain. Interiors are exposed panel faces or stained mill boards. Partial height walls denote areas of more privacy. The process of assembling the Eco-Huts on-site and disassembling them in the future determined the material pallet of dimensional lumber and pre-assembled wood window walls. The prototype incorporates modular concepts enabling variation in floor plan and amenities in direct response to the Owner’s request for market flexibility.

Conceived to have minimal footprints on the land, the Huts rest on piers elevating the floor above the land and accommodating the undulating landscape. A modular dimension was chosen permitting variation in the Eco-Hut sizes. The floor, walls, and roof planes are built off-site and tilted in place. Exterior stained wood material varying from plywood to sawn boards were chosen to harmonize with the High Desert landscape and be of minimal maintenance to the Tribes. Plywood panels are dressed with battens and either in-set from the wood framing or installed flush to the exterior. Sawn mill boards are stained dark desert grey and applied horizontally to create solid side walls atop of which are placed ribbon windows. The primary entry and view wall is a wood frame window and door façade. A deep roof overhang protects the interior from solar gain. Interiors are exposed panel faces or stained mill boards. Partial height walls denote areas of more privacy. The process of assembling the Eco-Huts on-site and disassembling them in the future determined the material pallet of dimensional lumber and pre-assembled wood window walls. The prototype incorporates modular concepts enabling variation in floor plan and amenities in direct response to the Owner’s request for market flexibility. Inherent in our design approach for the Eco-Huts is the creation of design solutions that emphasize the uniqueness of Place. The concept includes Land Restoration and Land Stewardship. PMA’s goals when designing the prototypes was to help enhance the natural beauty of the river edge by integrating a built structure into the landscape that has minimal disturbance to the site and will leave no footprint when removed. Willows, sedges, and juniper will be planted to provide riparian cover along the Deschutes River in an effort to increase fish habitat and mitigate flooding. The plantings will also help mitigate visual impact from the river. The lumber mill site’s river edge offers an opportunity to create an employee park and river restoration replacing equipment storage and log staging. The Eco-Huts offer an opportunity to test the integration of stewardship planning and place design.

Inherent in our design approach for the Eco-Huts is the creation of design solutions that emphasize the uniqueness of Place. The concept includes Land Restoration and Land Stewardship. PMA’s goals when designing the prototypes was to help enhance the natural beauty of the river edge by integrating a built structure into the landscape that has minimal disturbance to the site and will leave no footprint when removed. Willows, sedges, and juniper will be planted to provide riparian cover along the Deschutes River in an effort to increase fish habitat and mitigate flooding. The plantings will also help mitigate visual impact from the river. The lumber mill site’s river edge offers an opportunity to create an employee park and river restoration replacing equipment storage and log staging. The Eco-Huts offer an opportunity to test the integration of stewardship planning and place design.