Presently, the City of Portland awarded a contract for Spectator Facilities Construction Project Management Services for a yet unnamed Veterans Memorial Coliseum project. The city is preparing for potential renovation scenarios. The uncertain future of the Coliseum feels like déjà vu.

Presently, the City of Portland awarded a contract for Spectator Facilities Construction Project Management Services for a yet unnamed Veterans Memorial Coliseum project. The city is preparing for potential renovation scenarios. The uncertain future of the Coliseum feels like déjà vu.

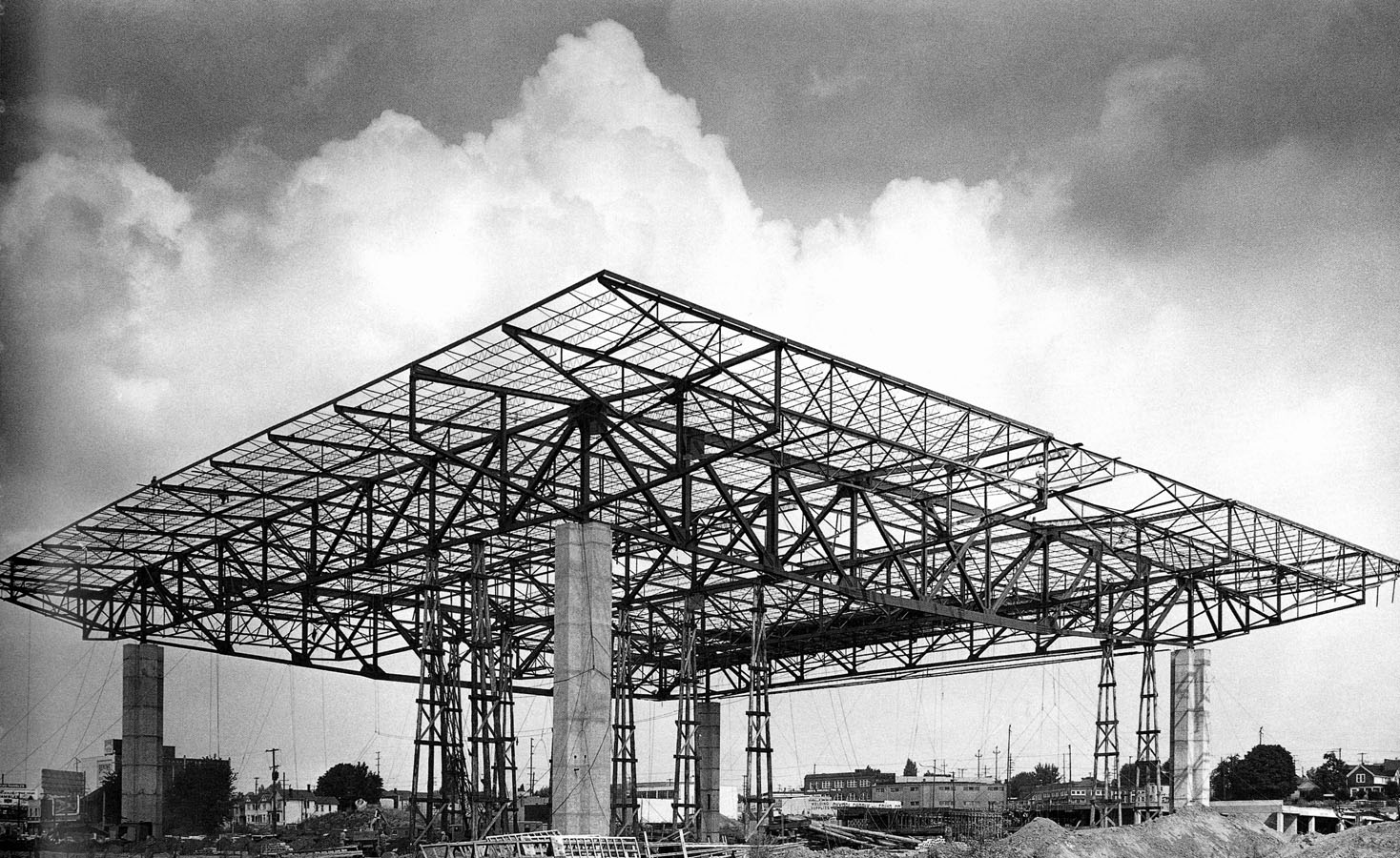

Portland’s Veterans Memorial Coliseum, designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) and built between 1960 and 1961, is a premier jewel of International Style modernism in the city. The structure consists of glass and aluminum, a non-load-bearing curtain wall cube with a central ovular concrete seating area. It is a true engineering and architectural masterpiece that offers uninterrupted panoramic views of Portland from the seating area. The Veterans Memorial Coliseum is also a war memorial, featuring exterior sunken black granite walls inscribed with the names of veterans in gold paint.

At its completion it was the largest multipurpose facility in the Pacific Northwest. And a significant structure within the larger urban planning Rose Quarter Development project. In 2009 the city of Portland proposed to demolish the Coliseum to make way for a new sports facility. The greater community of Portland, including architectural preservationists and historians, successfully applied for National Register of Historic Places status for the building. In 2011 it was placed in the National Register.

Portland’s Veterans Memorial Coliseum is a phenomenal renovation opportunity from both historic and economic perspectives.

Despite being listed in the National Register, built during an era of urban and planning reform that advocated for the latest in building technologies, and designed by one of our countries leading modernist firms, many challenge its architectural value. The Coliseum shows the remarkable and collaborative approach towards design and construction by SOM. It is also the only arena world-wide with a 360-degree panoramic view from the seating area. Consider the inability to experience this modern architectural marvel and war memorial firsthand. Simply put, the demolition of the Veterans Memorial Coliseum would be a loss to the city.

Concerns regarding its deferred maintenance and historic materials are often attached to the illogical demolition conclusion because the building does not meet specific 2014 building codes. It is possible to integrate new building technologies while retaining the building’s exterior and interior character defining features. Unfortunately, significant modernist architecture designed by influential architects in the 1950s-1970s have not been regarded with proper facility maintenance. Deferred maintenance has its price. Regardless of building age, if a structure is not properly maintained it will fall into disrepair. Thankfully, Portland has a robust AEC industry dedicated to solving design challenges.

As a city, Portland boast’s its commitment to living green and investing in sustainable practices throughout the greater community. The renovation of the Veterans Memorial Coliseum is exactly the type of project that would highlight our city’s commitment to sustainability. There is no greener option than renovating and reusing existing architectural resources. This renovation would also economically benefit the city by boosting investment around the Rose Quarter area. Potentially extending and overlapping with the renewed development interest in the Lloyd District. Portland could have two premier sports facilities, doubling the city’s ability to provide world-class sports and entertainment events. It is a renovation project with long term urban renewal benefits.

Veterans Memorial Coliseum is an internationally recognized architectural masterpiece. Its architectural legacy is deeply intertwined within Portland’s socio-economic and cultural heritages. Portland must learn from the recent demolitions of modernist architectural marvels like Prentice Women’s Hospital, several Paul Rudolph buildings, and the forthcoming Astrodome. Threats to our modern architecture is a threat to our architectural heritage. It is time to celebrate the last fifty years of Portland’s international jewel with a thoughtful renovation that looks ahead to the city’s next fifty years of architectural history.

Written by Kate Kearney, Marketing Coordinator

Are masonry sealers necessary on historic multi-wythe exterior walls? In general, likely not. Traditional exterior mass unit masonry walls, 3 to 4 wythes thick, leak. But rarely does the amount of water intrusion cause damage to the masonry, the masonry ties, or the interior finishes. Why wouldn’t a sealer be effective for these older walls?

Are masonry sealers necessary on historic multi-wythe exterior walls? In general, likely not. Traditional exterior mass unit masonry walls, 3 to 4 wythes thick, leak. But rarely does the amount of water intrusion cause damage to the masonry, the masonry ties, or the interior finishes. Why wouldn’t a sealer be effective for these older walls?  The porosity and absorption rates of older masonry are often exaggerated because of the brick appearance. Many older masonry units show the results of imperfect firing techniques. It is not unusual to see older masonry with vertical and horizontal cracks due to low firing temperatures or impurities in the original clay mix. The surface cracks may lead to higher rates of absorption around the crack but rarely increase the overall absorption or alter the overall characteristics of the masonry. Masonry sealers will not bridge these firing cracks.

The porosity and absorption rates of older masonry are often exaggerated because of the brick appearance. Many older masonry units show the results of imperfect firing techniques. It is not unusual to see older masonry with vertical and horizontal cracks due to low firing temperatures or impurities in the original clay mix. The surface cracks may lead to higher rates of absorption around the crack but rarely increase the overall absorption or alter the overall characteristics of the masonry. Masonry sealers will not bridge these firing cracks.

To control water intrusion and to increase performance of a masonry wall, it is much more effective to maintain mortar joints through re-pointing process, assure that mortar joints have no voids, replace brick with spalled faces, replace brick that are cracked the full depth, and repair bond line failures. The use of masonry sealers should be based on known research and field tested success and not chosen as a means to remedy poor construction methods.

To control water intrusion and to increase performance of a masonry wall, it is much more effective to maintain mortar joints through re-pointing process, assure that mortar joints have no voids, replace brick with spalled faces, replace brick that are cracked the full depth, and repair bond line failures. The use of masonry sealers should be based on known research and field tested success and not chosen as a means to remedy poor construction methods.

When severe deterioration of masonry walls is not a prevalent condition, what other non-visual processes are employed to determine the cause of deterioration? Two common techniques, well known to historic preservation professionals, are non-destructive testing (NDT) and material testing in the laboratory. NDE methods include RILEM tube water absorption tests, metal detector scanning, video scopes, infra-red photography, ultra sound testing, ground penetrating radar, and in some cases, x-ray diffraction. Common laboratory testing include petrographic examination, electron microscopy, and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) methods.

When severe deterioration of masonry walls is not a prevalent condition, what other non-visual processes are employed to determine the cause of deterioration? Two common techniques, well known to historic preservation professionals, are non-destructive testing (NDT) and material testing in the laboratory. NDE methods include RILEM tube water absorption tests, metal detector scanning, video scopes, infra-red photography, ultra sound testing, ground penetrating radar, and in some cases, x-ray diffraction. Common laboratory testing include petrographic examination, electron microscopy, and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) methods.  FTIR, when combined with the diagnostic RILEM tube field test, in particular is an effective evaluation to determine if masonry sealers have been applied to a wall surface impeding the capillary evaporation of trapped water. RILEM tests also provide an observation of a masonry wall’s initial rate of absorption under wind driven rain circumstances. Petrographic analysis of both masonry and mortars determines the material composition and will identify harmful natural elements and harmful additive elements like salts.

FTIR, when combined with the diagnostic RILEM tube field test, in particular is an effective evaluation to determine if masonry sealers have been applied to a wall surface impeding the capillary evaporation of trapped water. RILEM tests also provide an observation of a masonry wall’s initial rate of absorption under wind driven rain circumstances. Petrographic analysis of both masonry and mortars determines the material composition and will identify harmful natural elements and harmful additive elements like salts. A common misconception in the northwest is that surface spalls are a result of freeze thaw cycles. Freeze thaw susceptibility can only be determined through laboratory testing. Visual observations are insufficient to conclude masonry spalls resulted from freeze thaw forces. Since freeze thaw tests are graded either pass or fail, further tests methods are typically required for additional diagnostic evaluation. More likely sources of surface spalls are hard Portland cement mortars which exceed the strength of the masonry, salts introduced into the masonry through incorrect material selection, or surface sealers impeding the evaporation of water and thus creating a saturated sub surface layer which will freeze. (It is important to distinguish that the masonry unit may not be susceptible to freeze thaw but rather the sealer creates a dam like effect inducing a layer of water subject to freezing)

A common misconception in the northwest is that surface spalls are a result of freeze thaw cycles. Freeze thaw susceptibility can only be determined through laboratory testing. Visual observations are insufficient to conclude masonry spalls resulted from freeze thaw forces. Since freeze thaw tests are graded either pass or fail, further tests methods are typically required for additional diagnostic evaluation. More likely sources of surface spalls are hard Portland cement mortars which exceed the strength of the masonry, salts introduced into the masonry through incorrect material selection, or surface sealers impeding the evaporation of water and thus creating a saturated sub surface layer which will freeze. (It is important to distinguish that the masonry unit may not be susceptible to freeze thaw but rather the sealer creates a dam like effect inducing a layer of water subject to freezing) By combining visual observations with NDE and lab testing, most surface masonry deterioration can be determined and thereby implement proper repair, maintenance, and protection methods.

By combining visual observations with NDE and lab testing, most surface masonry deterioration can be determined and thereby implement proper repair, maintenance, and protection methods. Our first choice, and ethical preference, is to retain historic wood windows. Repaired and maintained wood windows constructed of old growth lumber will outlast any modern alternative. We advocate strongly for a process and philosophy that seriously evaluates retaining original material. The best approach compares long-term costs, embodied energy, and cultural importance relative to the same criteria for new replacement material.

Our first choice, and ethical preference, is to retain historic wood windows. Repaired and maintained wood windows constructed of old growth lumber will outlast any modern alternative. We advocate strongly for a process and philosophy that seriously evaluates retaining original material. The best approach compares long-term costs, embodied energy, and cultural importance relative to the same criteria for new replacement material. Most existing, older properties have had more than one owner. Research into original design documents, major rehabilitation projects, building permit requests, and other documents provide insight into processes that might have replaced original material. The removal and replacement of non-original material is justifiable and acceptable rationale.

Most existing, older properties have had more than one owner. Research into original design documents, major rehabilitation projects, building permit requests, and other documents provide insight into processes that might have replaced original material. The removal and replacement of non-original material is justifiable and acceptable rationale.  After a thorough evaluation and understanding of the existing wood windows, the next decision is to choose a replacement product. In-kind replacement,(i.e. wood window for wood window; true divided lites for true divided lites, matching pane divisions, etc.) is preferred. When the replacement window is virtually identical to the historic window, it is hard to say no. Absent exact replacement, the visual qualities exhibited by the cross section profiles, the sash height and width, and the proportion of wood to glazing, are the most important attributes to match. Appearance from the exterior will trump appearance from the interior during a historic review approval process.

After a thorough evaluation and understanding of the existing wood windows, the next decision is to choose a replacement product. In-kind replacement,(i.e. wood window for wood window; true divided lites for true divided lites, matching pane divisions, etc.) is preferred. When the replacement window is virtually identical to the historic window, it is hard to say no. Absent exact replacement, the visual qualities exhibited by the cross section profiles, the sash height and width, and the proportion of wood to glazing, are the most important attributes to match. Appearance from the exterior will trump appearance from the interior during a historic review approval process. When an opportunity to retain original fabric/windows is available, the opportunity should be incorporated into the work. Even retaining as little as 20% of historic fabric will increase the likelihood of approval for replacement of the remaining components. The retention of historic fabric also allows successive generations to better understand the history and changes of an existing property.

When an opportunity to retain original fabric/windows is available, the opportunity should be incorporated into the work. Even retaining as little as 20% of historic fabric will increase the likelihood of approval for replacement of the remaining components. The retention of historic fabric also allows successive generations to better understand the history and changes of an existing property.

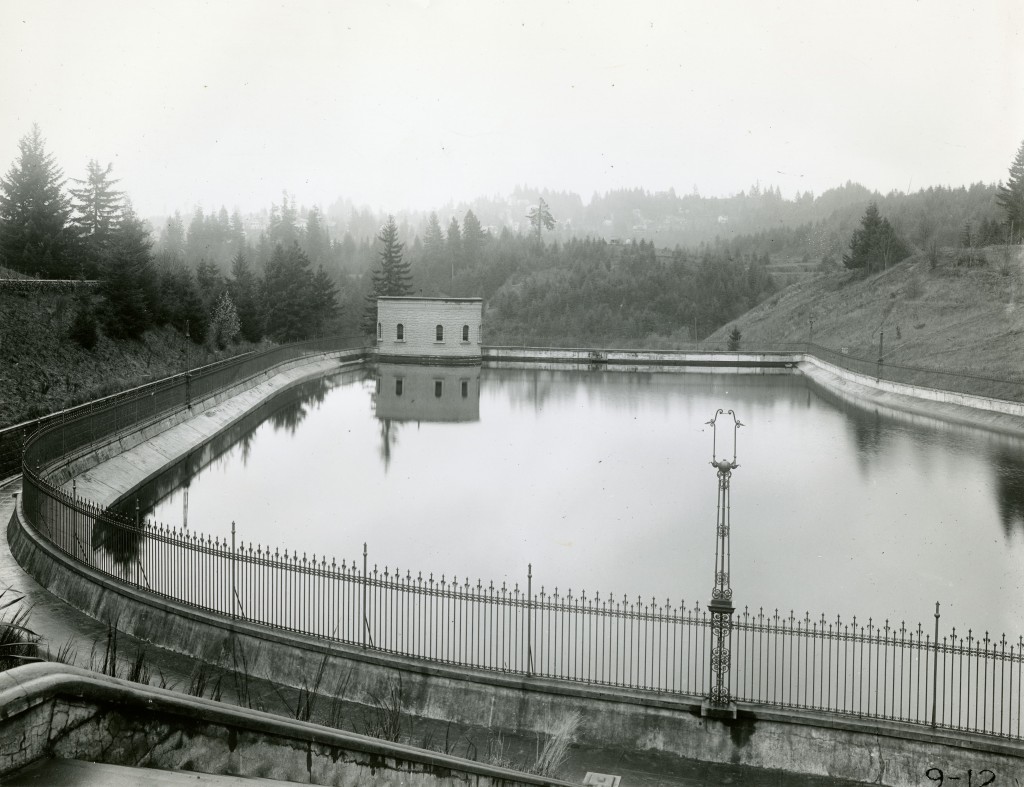

Washington Park Reservoirs is a historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It was developed to store and distribute clean drinking water, but it had another important function which drove its design: it was a recreational destination for a growing urban population. At the end of the 19th Century, the City Beautiful movement across American cities inspired planners and politicians to create parks as refuges from urban life. Parks were seen as restorative, where citizens could breathe fresh air, stroll along paths or promenades, and view natural plants, lakes, and garden vistas. Many of our most famous American parks were developed during the City Beautiful era, including Central Park in New York City.

Washington Park Reservoirs is a historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It was developed to store and distribute clean drinking water, but it had another important function which drove its design: it was a recreational destination for a growing urban population. At the end of the 19th Century, the City Beautiful movement across American cities inspired planners and politicians to create parks as refuges from urban life. Parks were seen as restorative, where citizens could breathe fresh air, stroll along paths or promenades, and view natural plants, lakes, and garden vistas. Many of our most famous American parks were developed during the City Beautiful era, including Central Park in New York City.

The Washington Park Reservoir area shows the most profound shift in use over time. The need to cover and further protect drinking water in underground storage contains in lieu of open Reservoirs reflects a growing national divide between government and the public made visible by current limited access to a once prominent bucolic public destination. Perhaps a certain level of distrust is to be expected from decisions affecting public safety, but the potential loss of the Reservoirs as a contemplative, experiential destination is in stark contrast to the one of original design intent. Part of the current limited access results from the explosion in liability, where government agencies can and will be found at fault for any harm that might befall a park user or a water consumer. Federal regulations requiring municipal drinking water to be covered also feed our collective sense that there are malicious people among us.

The Washington Park Reservoir area shows the most profound shift in use over time. The need to cover and further protect drinking water in underground storage contains in lieu of open Reservoirs reflects a growing national divide between government and the public made visible by current limited access to a once prominent bucolic public destination. Perhaps a certain level of distrust is to be expected from decisions affecting public safety, but the potential loss of the Reservoirs as a contemplative, experiential destination is in stark contrast to the one of original design intent. Part of the current limited access results from the explosion in liability, where government agencies can and will be found at fault for any harm that might befall a park user or a water consumer. Federal regulations requiring municipal drinking water to be covered also feed our collective sense that there are malicious people among us.  Amazingly, the Halprin Open Space Sequence continues to survive the “age of liability” with its wonderful interactive fountains, plazas, and pools intact. Nothing this fun- and potentially hazardous- will likely be constructed again as a public project. The design reminds us that we must be responsible for protecting this level of freedom, and that this very public- and yes, democratic- open space, is uniquely valuable as a symbol of public trust.

Amazingly, the Halprin Open Space Sequence continues to survive the “age of liability” with its wonderful interactive fountains, plazas, and pools intact. Nothing this fun- and potentially hazardous- will likely be constructed again as a public project. The design reminds us that we must be responsible for protecting this level of freedom, and that this very public- and yes, democratic- open space, is uniquely valuable as a symbol of public trust.