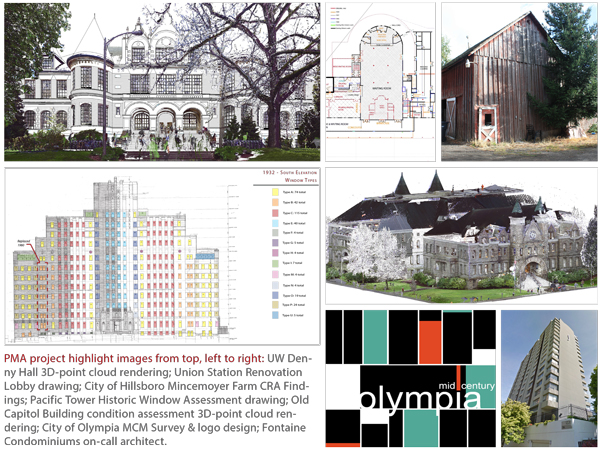

Portland’s Union Station is the only major railroad station built in Oregon, and one of the oldest major extant passenger terminals on the West Coast. From its inception, Union Station has functioned as a major transportation link to Portland and the west coast, with a continued vital role to play in future rail and multimodal transportation planning.

A Sense of Place

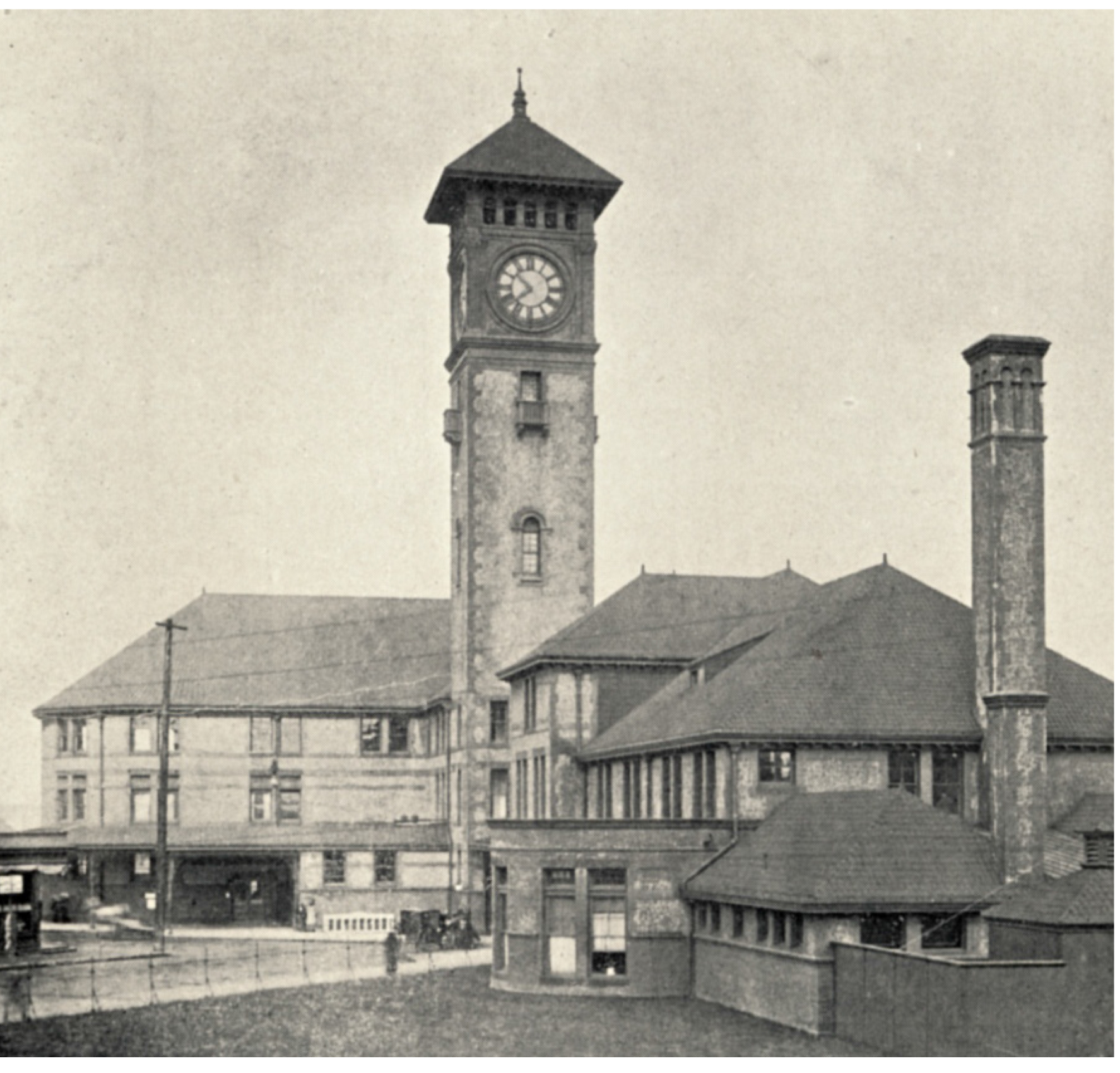

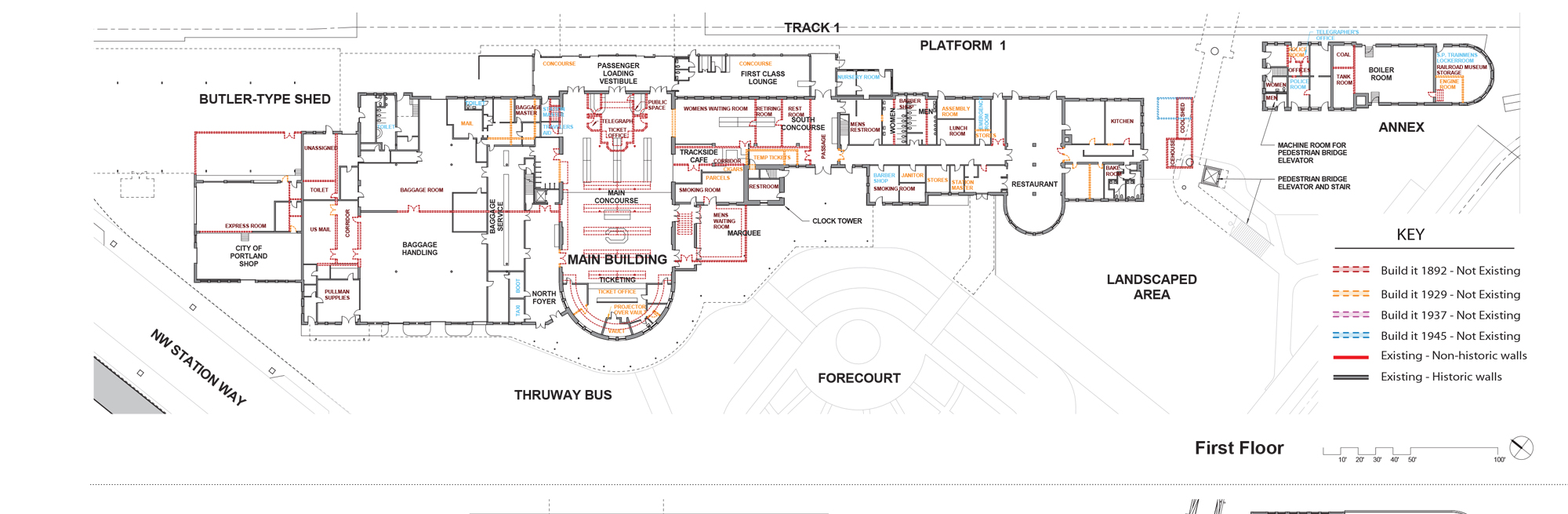

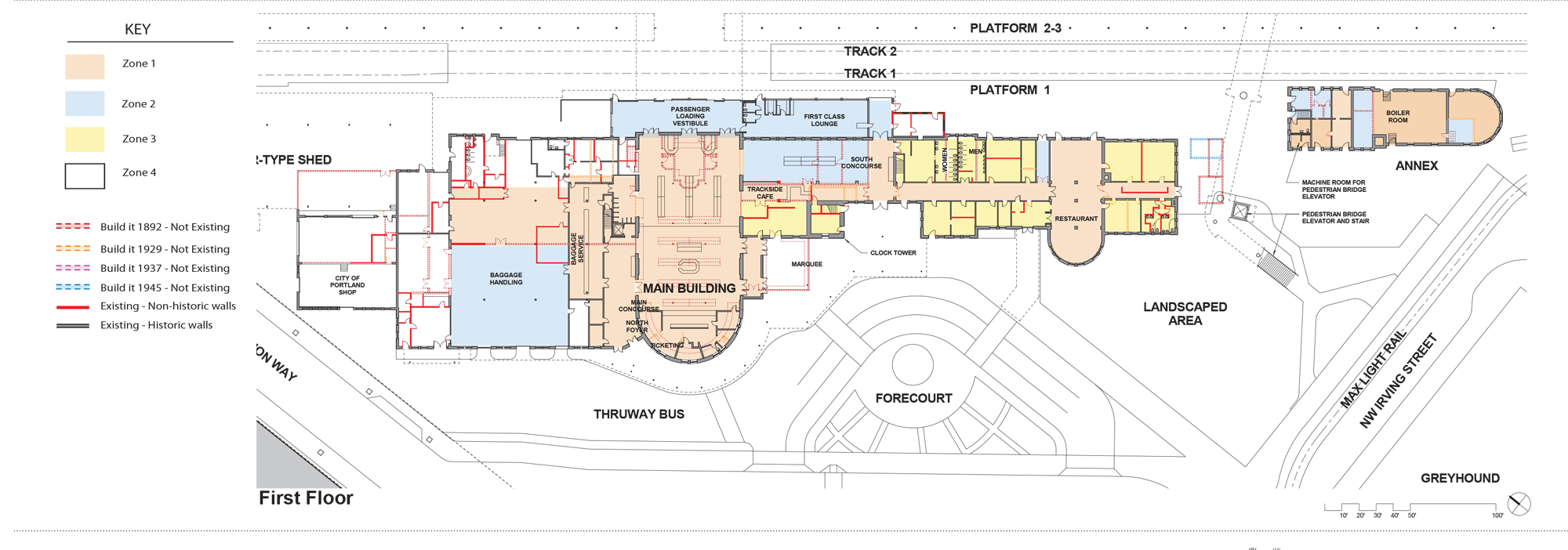

Critical to adapting Union Station, and other historic structures, for current and future use is to thoroughly understand key elements and components that convey the sense of place and rich history of the structure. A deeper understanding enables informed decisions to be made about the potential of key characteristics to remain for future generations. Union Station was constructed between 1892 and 1894 and was designed by Van Brunt & Howe architects in the Queen Anne style with Romanesque detail. From 1927 thru 1930, the Main Concourse was modernized by Portland’s internationally known architect, Pietro Belluschi, to reflect the streamline era of rail technology. Like the original 1892 elements, the Belluschi modernization’s are equally important stories to tell.

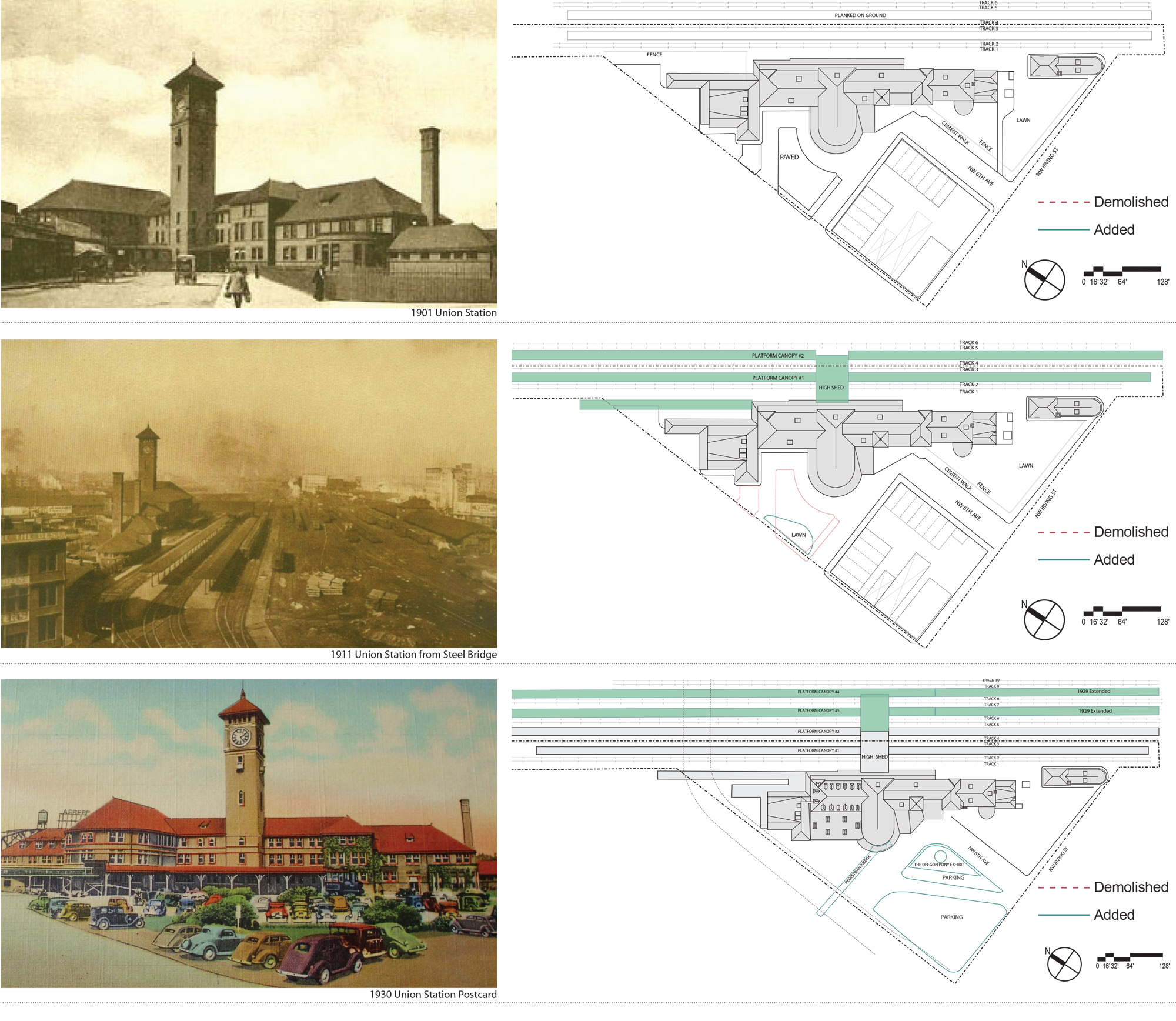

Creating a graphic document annotating “changes over time” is an essential tool for evaluating how Union Station has adapted to improvements in rail technology, fluctuations in passenger volume, cultural shifts regarding train travel, as well as modifications to specific architectural elements that impact the historic integrity and interpretation of original design intent.

Methodology for Assessment

Our method of developing the graphic drawing is to compare historic floor plans and historic photographs to current plans and images through a process of layering plans from different eras over one another and drawing the altered, or missing, elements (e.g. walls, furniture, spaces, etc.) in different colors. This methodology provides an easily interpreted floor plan. The use of color enhances the image and creates a visual record of both changes and original historic fabric. In reading the graphic drawing, it becomes readily discernible that changes include: wood floors replaced with concrete and new floors added; openings in the main concourse were moved and enlarged; the women’s waiting room and toilet were removed to widen the south hall, the stairs were renovated, and a new baggage counter was constructed. The covered concourse was glassed in and a section was made into the First Class Lounge, which remains today. And in the 1940s, a nursery, or crying, room was added.

What is fascinating about the history of a building like Union Station, is that the rail lines and street patterns are also integrated with the function and use of the structure and have changed over time as well. The construction of Union Station came soon after Portland was fully connected by rail in 1883 to California, Montana, and rail lines running to the East Coast across the U.S. The Spokane-Portland-Seattle rail connection was finished in 1908. In 1922, Union Station became accessible to all major passenger railroads operating through Portland.

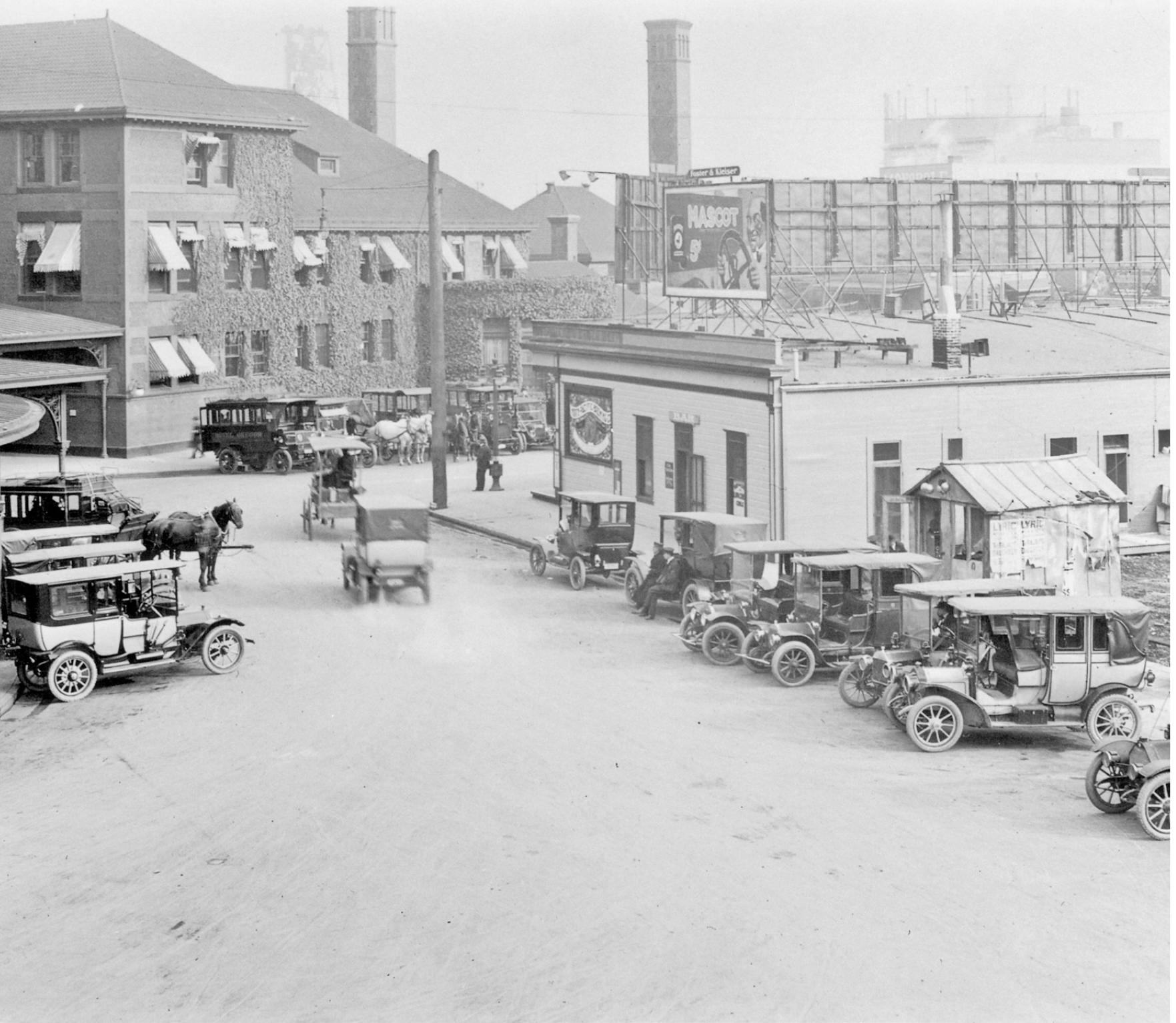

When originally constructed, six passenger car rail lines approached the rear of Union Station. The waiting platform consisted of planks on dirt with no canopy. The block across from Union Station consisted of a small restaurant, bar, other stores, and stables. A five foot iron fence bordered a large lawn and sidewalk to the south and west of the station. The High Shed, a large two-story metal shed was the first canopy built to cover the passenger platforms and extended perpendicular to the station. Under this High Shed, two smaller scale platform canopies were erected paralleling the tracks. A mail canopy was built at the north end of the building in 1915.

By 1920, the block across from Union Station’s main entrance had been converted to parking to relieve congestion. As automobile use increased throughout the city, parking configurations were constantly changing over the years. By 1923, an elevated walkway was built to connect the Broadway Bridge to the main entrance.

With the introduction of larger diesel locomotives and potential for high speed rail along the northwest corridor, the track, platforms, and canopies have had to be modified. Safety and accessibility have also driven the need for changes and modernization. Documenting these alterations with graphics, provides a foundation from which to advocate for further refinement while recognizing historic precedent and protection of historic elements.

Written by Peter Meijer, AIA,NCARB, Principal

PMA is part of the DOWA-IBI Group team for this exciting PDC Union Station Renovation Project.

Greatly influenced by the 1936 publication of John Yeon’s Watzek House, Oregon architects began to experiment with wood skins and “Mt. Hood” entry facades reminiscent of Yeon’s design. The idea that wood was symbolic of Northwest character continued through the 1950s and 1960s mid-century modern aesthetics. Local architects like Francis Jacobberger, McCoy & Bradbury, Pietro Belluschi, and others crafter their designs from outside to inside using local species of wood while simultaneously using wood to express the structural elements.

Greatly influenced by the 1936 publication of John Yeon’s Watzek House, Oregon architects began to experiment with wood skins and “Mt. Hood” entry facades reminiscent of Yeon’s design. The idea that wood was symbolic of Northwest character continued through the 1950s and 1960s mid-century modern aesthetics. Local architects like Francis Jacobberger, McCoy & Bradbury, Pietro Belluschi, and others crafter their designs from outside to inside using local species of wood while simultaneously using wood to express the structural elements.

Well known Oregon artists, including Ray Grimm, a ceramists, created the dominating Tree of Life mosaic on the west façade. LeRoy Setziol, the “Father of Wood Carving in Oregon,” created the wood Stations of the Cross and baptismal font. Surprisingly Setziol was commissioned to execute the stained glass windows as well. And Lee Kelly, one of Portland’s best known metal sculptors, enriched the church with delicate displays of metal work both on the interior and exterior. Queen of Peace is a marvelous collaboration of architecture, art, and technical daring creating a wonderful display of Oregon indigenous mid-century religious architecture.

Well known Oregon artists, including Ray Grimm, a ceramists, created the dominating Tree of Life mosaic on the west façade. LeRoy Setziol, the “Father of Wood Carving in Oregon,” created the wood Stations of the Cross and baptismal font. Surprisingly Setziol was commissioned to execute the stained glass windows as well. And Lee Kelly, one of Portland’s best known metal sculptors, enriched the church with delicate displays of metal work both on the interior and exterior. Queen of Peace is a marvelous collaboration of architecture, art, and technical daring creating a wonderful display of Oregon indigenous mid-century religious architecture.

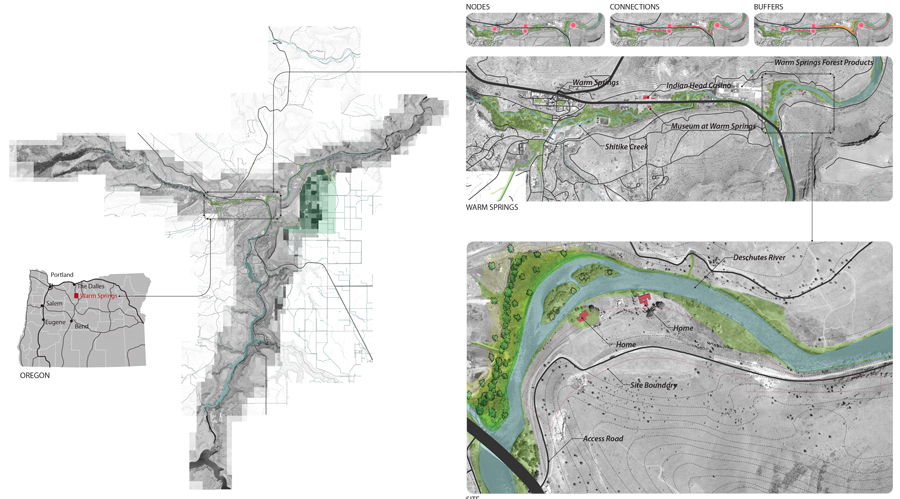

Projects that integrate building science, stewardship planning, and place design are simultaneously exciting and challenging. Any one of the three core concepts can drive the decision making process resulting in a number of solutions. Our current concepts for minimalist eco structures, or “Huts” in the beautiful High Desert of Eastern Oregon are a fantastic challenge.

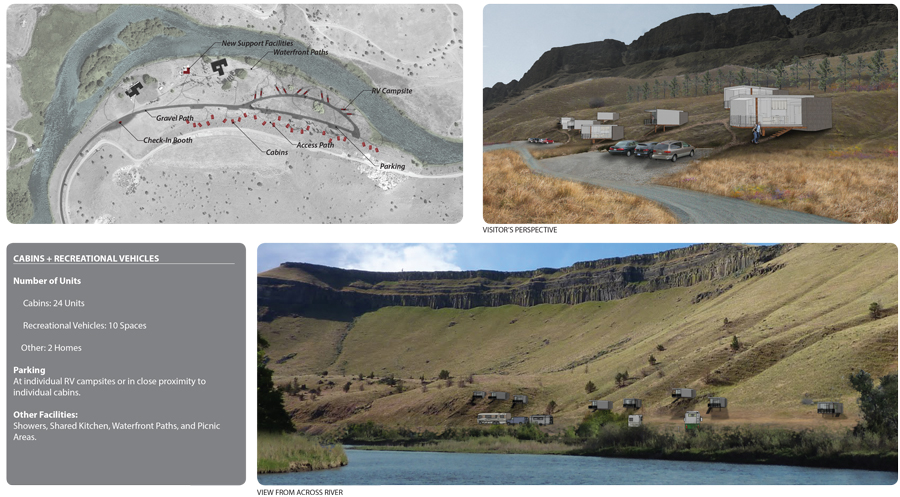

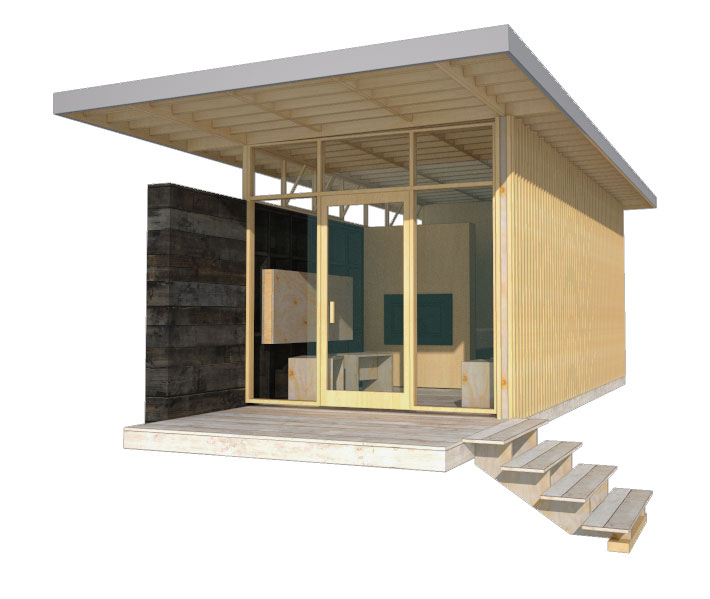

Projects that integrate building science, stewardship planning, and place design are simultaneously exciting and challenging. Any one of the three core concepts can drive the decision making process resulting in a number of solutions. Our current concepts for minimalist eco structures, or “Huts” in the beautiful High Desert of Eastern Oregon are a fantastic challenge. Working with the The Confederate Tribes of Warm Springs, PMA created a prototype model, easily constructed and assembled off site (test fit), then transported to the site and efficiently erected. The prototype was designed to be economical and constructed from lumber from the local lumber mill that produces products from high desert pines. A contemporary design style was chosen to harmonize with existing mid-century Belluschi homes on the property. Both the Belluschi homes and the Eco-Huts stand in contrast with the landscape and topography.

Working with the The Confederate Tribes of Warm Springs, PMA created a prototype model, easily constructed and assembled off site (test fit), then transported to the site and efficiently erected. The prototype was designed to be economical and constructed from lumber from the local lumber mill that produces products from high desert pines. A contemporary design style was chosen to harmonize with existing mid-century Belluschi homes on the property. Both the Belluschi homes and the Eco-Huts stand in contrast with the landscape and topography.

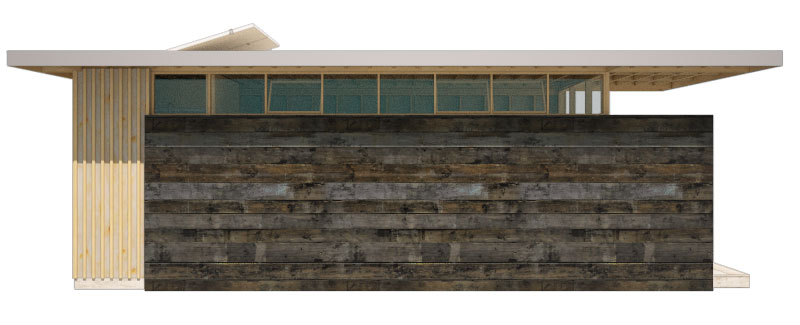

Conceived to have minimal footprints on the land, the Huts rest on piers elevating the floor above the land and accommodating the undulating landscape. A modular dimension was chosen permitting variation in the Eco-Hut sizes. The floor, walls, and roof planes are built off-site and tilted in place. Exterior stained wood material varying from plywood to sawn boards were chosen to harmonize with the High Desert landscape and be of minimal maintenance to the Tribes. Plywood panels are dressed with battens and either in-set from the wood framing or installed flush to the exterior. Sawn mill boards are stained dark desert grey and applied horizontally to create solid side walls atop of which are placed ribbon windows. The primary entry and view wall is a wood frame window and door façade. A deep roof overhang protects the interior from solar gain. Interiors are exposed panel faces or stained mill boards. Partial height walls denote areas of more privacy. The process of assembling the Eco-Huts on-site and disassembling them in the future determined the material pallet of dimensional lumber and pre-assembled wood window walls. The prototype incorporates modular concepts enabling variation in floor plan and amenities in direct response to the Owner’s request for market flexibility.

Conceived to have minimal footprints on the land, the Huts rest on piers elevating the floor above the land and accommodating the undulating landscape. A modular dimension was chosen permitting variation in the Eco-Hut sizes. The floor, walls, and roof planes are built off-site and tilted in place. Exterior stained wood material varying from plywood to sawn boards were chosen to harmonize with the High Desert landscape and be of minimal maintenance to the Tribes. Plywood panels are dressed with battens and either in-set from the wood framing or installed flush to the exterior. Sawn mill boards are stained dark desert grey and applied horizontally to create solid side walls atop of which are placed ribbon windows. The primary entry and view wall is a wood frame window and door façade. A deep roof overhang protects the interior from solar gain. Interiors are exposed panel faces or stained mill boards. Partial height walls denote areas of more privacy. The process of assembling the Eco-Huts on-site and disassembling them in the future determined the material pallet of dimensional lumber and pre-assembled wood window walls. The prototype incorporates modular concepts enabling variation in floor plan and amenities in direct response to the Owner’s request for market flexibility. Inherent in our design approach for the Eco-Huts is the creation of design solutions that emphasize the uniqueness of Place. The concept includes Land Restoration and Land Stewardship. PMA’s goals when designing the prototypes was to help enhance the natural beauty of the river edge by integrating a built structure into the landscape that has minimal disturbance to the site and will leave no footprint when removed. Willows, sedges, and juniper will be planted to provide riparian cover along the Deschutes River in an effort to increase fish habitat and mitigate flooding. The plantings will also help mitigate visual impact from the river. The lumber mill site’s river edge offers an opportunity to create an employee park and river restoration replacing equipment storage and log staging. The Eco-Huts offer an opportunity to test the integration of stewardship planning and place design.

Inherent in our design approach for the Eco-Huts is the creation of design solutions that emphasize the uniqueness of Place. The concept includes Land Restoration and Land Stewardship. PMA’s goals when designing the prototypes was to help enhance the natural beauty of the river edge by integrating a built structure into the landscape that has minimal disturbance to the site and will leave no footprint when removed. Willows, sedges, and juniper will be planted to provide riparian cover along the Deschutes River in an effort to increase fish habitat and mitigate flooding. The plantings will also help mitigate visual impact from the river. The lumber mill site’s river edge offers an opportunity to create an employee park and river restoration replacing equipment storage and log staging. The Eco-Huts offer an opportunity to test the integration of stewardship planning and place design.

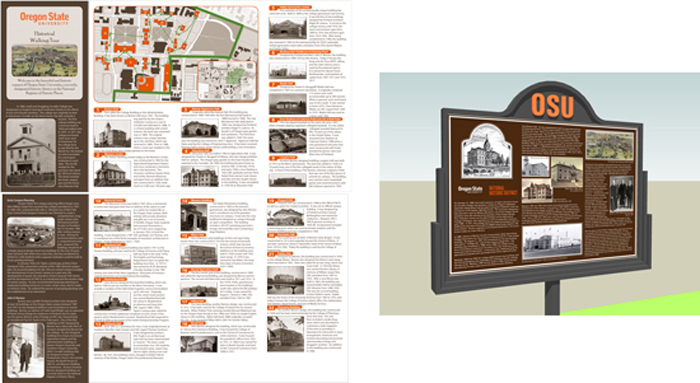

PMA has been involved with several architectural planning projects that center on significant structures from the Mid-Century Modern era. These projects surveyed and documented hundreds of architecturally significant structures that revolutionized architecture and design throughout the 20th century. On the surface such planning projects can be difficult for a wide audience to understand and appreciate because the final project is not a new or renovated building(s). What better opportunity then, for graphic design to communicate and connect the significance of the project and its structures. For these projects, project logos and marketing collateral were designed as the visual symbols that communicate the entire identity of the projects. While both projects surveyed Mid-Century structures one focused on residential structures while the other did not. Both logos use form with text and color to help shape the sense of which type of mid-century modern structures were surveyed.

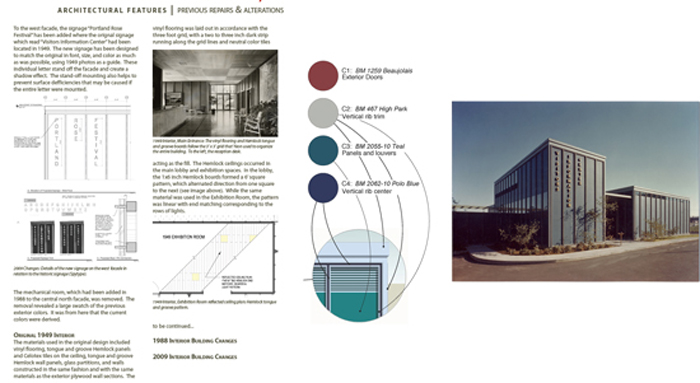

PMA has been involved with several architectural planning projects that center on significant structures from the Mid-Century Modern era. These projects surveyed and documented hundreds of architecturally significant structures that revolutionized architecture and design throughout the 20th century. On the surface such planning projects can be difficult for a wide audience to understand and appreciate because the final project is not a new or renovated building(s). What better opportunity then, for graphic design to communicate and connect the significance of the project and its structures. For these projects, project logos and marketing collateral were designed as the visual symbols that communicate the entire identity of the projects. While both projects surveyed Mid-Century structures one focused on residential structures while the other did not. Both logos use form with text and color to help shape the sense of which type of mid-century modern structures were surveyed.  Following our planning projects centered on Mid-Century Modern architecture, PMA provided graphic design services for the renovation of the John Yeon designed Rose Festival Headquarters building (former Visitors Information Center). For this project, typography and color were the focal points for communicating the next chapter in this buildings life-cycle. The new graphics, color, and signage produced pay homage to the original design, while being entirely their own.

Following our planning projects centered on Mid-Century Modern architecture, PMA provided graphic design services for the renovation of the John Yeon designed Rose Festival Headquarters building (former Visitors Information Center). For this project, typography and color were the focal points for communicating the next chapter in this buildings life-cycle. The new graphics, color, and signage produced pay homage to the original design, while being entirely their own.

Presently, the City of Portland awarded a contract for Spectator Facilities Construction Project Management Services for a yet unnamed Veterans Memorial Coliseum project. The city is preparing for potential renovation scenarios. The uncertain future of the Coliseum feels like déjà vu.

Presently, the City of Portland awarded a contract for Spectator Facilities Construction Project Management Services for a yet unnamed Veterans Memorial Coliseum project. The city is preparing for potential renovation scenarios. The uncertain future of the Coliseum feels like déjà vu.